1492: The Year Our World Began (13 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

Those who got there suffered “all the curses of the Torah and more”—as one of them, who was ten years old at the time of the expulsion—later recalled.

15

They built shanties of straw. A conflagration consumed them, along with all the valuables and many collections of books in Hebrew. But for the survivors, Fez had, at least, the advantages of cosmopolitanism, and a corresponding tolerance of religious diversity and heterodoxy. Vestiges of Christian or pagan ceremonies dappled the culture. Irrespective of their creed, people served pulses at Christmas, and at New Years, Leo Africanus reported, masked children “have fruits given them for singing certaine carols or songs.” Divination and necromancy were rife, though proscribed, as Leo pointed out, by “Mahometan inquisitors.” Jewish learning had a market niche. Cabbalism was especially popular, its practitioners “never found to erre, which causeth their art of Cabala to be had in great admiration: which although it be accounted naturall, yet never saw I any thing that hath more affinitie with supernatural and divine knowledge.” Jews monopolized gold and silver work, forbidden to Muslims because of the usurious profits smiths made on the jewelwork they pawned.

16

To judge, however, from the account of Leo Africanus, the effects of the influx of fugitives from Spain were deleterious for the whole community of Jews in Fez. The Jews occupied one long street in the new city, “wherein they have their shops and their synagogues, and their number is marvellously encreased ever since they were driven out of Spaine.” The increase turned them into a minority too big to be welcome. Formerly favored, now victimized, they paid double the tribute traditionally due. “These Iewes,” Leo observed, “are had in great contempt by all men, neither are any of them permitted to wear shooes, but they make them certaine socks of sea-rushes.”

Tlemcen, which, like Fez, already had a large Jewish community, was another destination that looked attractive until the expulsees actually arrived. Leo “never saw a more pleasant place,” but in Tlemcen, as one of the Spanish refugees recalled, the newly arrived Jews roamed “naked,…clinging to the trash-heaps.”

17

Thousands of Jews died in a subsequent plague, but enough survived to exacerbate ethnic and religious tension. Though the Jews “in times past” were “all of them exceeding rich,” in riots during the interregnum of 1516 “they were all so robbed and spoiled that they are now brought almost unto beggerie.”

18

Alarmed citizens accused them of bringing syphilis: “Many of the Jews who came to Barbary…carried the disease from Spain…. Some unhappy Moors mixed with the Jewish women, and so, little by little, within ten years, one could not find a family untouched by the disease.” At first, sufferers were forced to live with lepers. The cure, according to Leo, was to breathe the air of the Land of the Blacks.

19

Some Jews gravitated toward the Atlantic coast of Morocco, where the kingdom of Fez was crumbling at the edges as herdsmen from the Sahara colonized farmland and reduced the wheat production for export, on which the rulers relied for tolls. In the ports of Safi and Azemmour, the power of Fez was barely felt, and control was in the hands of the leaders of pastoral tribes. But there was still enough arable land to grow some wheat, and the tribal big shots collaborated with Spanish and Portuguese efforts to acquire the surplus cheaply—

and often got bribes and even Iberian titles of nobility in return. In effect, the region became a joint Spanish-Portuguese condominium, or at least protectorate—a kind of free-port zone, exempt both from the control of the sultans in Fez and from the Church’s rules against trading with infidels.

The Jewish refugees were the perfect middlemen for this trade. Their expulsion from Spain had a dramatic effect on turnover, making the region Portugal’s main source of foreign wheat in the early sixteenth century. They also handled slaves, copper, and iron. The Zamero and Levi families specialized, in addition, in organizing the manufacture of the brightly colored woolen cloth that was prized in the gold-bearing regions south of the desert. In partial consequence, from 1492 or 1493, for the rest of the decade, Safi earned more West African gold than the fort of São Jorge.

20

Yet nowhere in the Maghreb, or even in the Sahel itself, could the Jews find perfect peace. The anti-Semitism of the rabid itinerant preacher al-Maghili pursued and harried them all over the Maghreb. In Tuat he inspired pogroms and acts of arson against Jewish homes and synagogues. He turned the Niger Valley into a danger zone after his preaching mission beyond the Sahara in 1498. In Songhay, Askia Muhammad became “a declared enemy of the Jews. He will not allow any to live in the city. If he hears it said that a Berber merchant frequents them or does business with them, he confiscates his goods and puts them in the royal treasury, leaving him scarcely enough money to get home.”

21

For Jews able to escape Spain via ports on the Mediterranean coast, Italy was an alluring destination. There were so many competing jurisdictions in that patchwork peninsula of many states of varying sizes that it was unlikely ever to be uniformly hostile to any group. Jews would always find a refuge somewhere. Sicily and Sardinia were closed: the King of Aragon controlled them and extended the terms of the expulsion from Spain to cover those islands. Naples was a temporary refuge, where most of the Jews, if plague spared them, fled again when Charles VIII of France conquered the city in 1494.

Meanwhile, as one of the exiles from Spain reported, “Italy and all the Levant became filled with…slavers and captives who owed their seamen the cost of their transport.” For many refugees, the best hope was to find a sympathetic Jewish community already in place and throw themselves on the mercy of their hosts. In Candia, in Venetian-ruled Crete, the father of the Jewish chronicler Elijah Capsali encountered “many mercies” and collected 250 florins for the relief of Jewish refugees in 1493. After many adventures, Judah ben Yakob Hayyat—whose travels were travails involving imprisonment in Tlemcen, enslavement in Fez, and surviving plague in Naples—found succor in Venice, where fellow Spaniards took pity on him. He also found a welcome in Mantua, where he died at peace among a well-established and secure Jewish community. For those who remained faithful to their religion, their miseries seemed like a trial of faith—a new sacred history of temptation by God, a new exodus leading to a new Canaan, or a reenactment of the torments of Job.

22

Among the most hospitable places were Venice and—ironically, perhaps—Rome. The former city was under the rule of a merchant patriciate, who knew better than to exclude potential wealth creators, while in Rome, the papacy had no reason to fear Jews and every interest in having them available to exploit. Like poor immigrants throughout the ages, Jews there adjusted to the jobs no one else would do. Early in the next century, Francisco Delicado, a convert from Judaism who moved between Rome and Venice, wrote one of the first novels of social realism,

La Lozana andaluza

(The Andalusian Waif), set in the Jewish and converso demimonde of Rome, where the inmates grubbed inconspicuous lives from brothels and gutters, in a world scarred by syphilis and smeared with filth. Ambiguity, adaptability, and evasion were the only means of survival in this world. It was easy to mistake them for dishonesty. A Roman essayist of the 1530s thought the city’s converts were shifty and lying—like Aesop’s bat, who represented himself as a mouse to a cockerel and as a bird to a cat. Solomon Ibn Verga was one of these mutable creatures. He masqueraded as a Christian in Lisbon and later returned to practice his

faith in safety in Rome, where he heard one of his fellow deportees exclaim, after all the sufferings of the journey,

Lord of the Universe! You have done much to make me forsake my religion, so let it be known faithfully, that despite those who dwell in heaven I am a Jew and will remain a Jew. And it makes no difference what you brought down upon me or bring down upon me!

23

But many of the exiles gave up, returned to Spain, and submitted to baptism. Andrés de Bernáldez recorded the baptisms of a hundred returnees from Portugal in his own parish at Los Palacios, near Seville. He saw others struggling back from Morocco, “naked, barefoot, and full of fleas, dying of hunger.”

24

The most secure destination for exiled Jews, where their communities and culture found a ready welcome and were able to survive and thrive for centuries to come, was the Ottoman Empire—one of the world’s fastest-expanding states, which covered almost the whole of Anatolia and Greece and much of southeastern Europe. Ottoman rulers had long represented themselves as warriors fighting to defend and strengthen Islam, but they maintained a culturally plural, confession-ally heterogeneous state in which Christians and Jews were tolerated but were subject to discriminatory taxation and burdensome forms of service to the state—the most notorious of which was the annual levy of Christian children, seized from their families, brought up as Muslims, and enslaved as soldiers or servants of the sultan. On the whole, the Ottomans preferred Jewish to Christian subjects: they were unlikely to sympathize with the empire’s enemies. Among the inducements that made Jews settle in Ottoman lands were fiscal privileges, free plots for housing, and freedom to build synagogues—in contrast with Christians, who could use existing churches in land the Ottomans conquered but who were not allowed to add to them.

An environment hospitable to religious exiles was the product of two generations of Ottoman expansion. While most other European

states were striving for the kind of strength that emerges from uniform identity, focused allegiance, and cultural unity, the Ottomans embarked on an experiment in empire building among culturally divergent peoples and the construction of unity in diversity. In the thirty years from his accession in 1451, Mehmet II devoted his time as sultan to this project. Before his time, Turks had a reputation as destructive raiders, “like torrential rains,” as one of Mehmet’s generals recalled in his memoirs.

…and everything this water strikes it carries away and, moreover, destroys…. But such sudden downpours do not last long. Thus also Turkish raiders…do not linger long, but wherever they strike they burn, plunder, kill and destroy everything so that for many years the cock will not crow there.

25

After Mehmet’s time it was impossible to continue to see Ottoman armies as raiders or Ottoman policies as destructive. Mehmet turned conquest into a constructive force, building the Ottoman state into a culturally flexible, potentially universal empire.

His predecessors had been conscious of a dual heritage: as paladins of Islam, and as heirs of steppeland conquerors with a vocation to rule the world. Without sacrificing those perceptions, Mehmet added a new image of himself as the legatee of ancient Greek civilization and the Roman Empire. He had Italian humanists at his court, who read to him every day from histories of Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great. He introduced new rules of court etiquette, combining Roman and Persian traditions. In 1453 he conquered Constantinople, where the people still called themselves Romans, and made it his capital. The city was bleak and bare when he conquered it—run down by generations of decline. Mehmet’s declared aim was “to make the city in every way the best supplied and strongest city as it used to be long ago, in power, wealth, and glory.”

26

To repopulate it and restore its glory, Mehmet was lavish with concessions to immigrants:

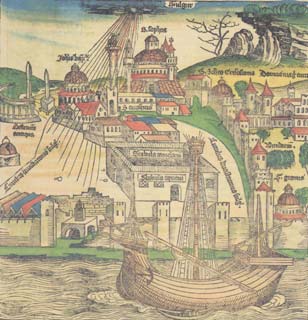

The port of Constantinople, with all the tourist sites known to the principal illustrators of the Nuremberg Chronicle, Michael Wohlgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff.

Nuremberg Chronicle.

Who among you of all my people that is with me, may his God be with him, let him ascend to Istanbul, the site of my imperial throne. Let him dwell in the best of the land, each beneath his vine and beneath his fig tree, with silver and gold, with wealth and with cattle. Let him dwell in the land, trade in it, and take possession of it.

According to one of the Ottomans’ Jewish subjects, Jews “gathered together from all the cities of Turkey” in response. At that time, rabbis in Mehmet’s pay circulated among Jewish victims of persecution and

local expulsions in Germany the fifteenth-century equivalent of promotional brochures. “I was driven out of my native country,” wrote one of them to fellow Jews he had left behind in Germany, “and came to the Turkish land, which is blessed by God and filled with good things. Here I found rest and happiness. Turkey can also become for you the land of peace.”

27

Long before the expulsion from Spain, Jewish networks had identified the Ottoman Empire as a suitable place for business and a safe destination for exiles.

Most of Mehmet’s other conquests were on his empire’s western front, south of the Danube, incorporating an ever-larger Christian subject population. He brought artists from Italy to his court, had himself portrayed in Renaissance style in portraits and medals, learned Greek and Latin, and taught himself the principles of Christianity in order to be able to understand his Christian subjects better. He realized that the key to successful state building lies in turning the conquered into allies or adherents. Oppression rarely works. He won the allegiance of most of the Christians of his empire. Indeed, they supplied many of the recruits to his armies. He opened high office to members of the Greek, Serb, Bulgarian, and Albanian aristocracies, though most of them were converts to Islam. He consciously straddled Europe and Asia. He called himself ruler of Anatolia and Rumelia, sultan and caesar, emperor of Turks and Romans, and master of two seas—the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. He began an intensive program of investment in his navy, and in 1480 a seaborne Turkish force captured the Italian city of Otranto. Mehmet seemed not only to want to invoke the Roman Empire, but to re-create it. The pope prepared to decamp from Rome, calling urgently for a new crusade.