1492: The Year Our World Began (19 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

Muscovy still depended on the Mongols. The principality’s first challenge to Mongol supremacy, in 1378–82, proved premature. The Muscovites tried to exploit divisions within the Golden Horde in order to avoid handing over taxes. They even beat off a punitive expedition. But once the Mongols had reestablished their unity, Muscovy had to resume payment, yield hostages, and stamp coins with the name of the khan and the prayer “Long may he live.” In 1399 the Mongols fought off a Lithuanian challenge to their control of Russia. Over the next few years they asserted their hegemony in a series of raids on Russian cities, including Moscow, extorting promises of tribute in perpetuity. Thereafter, the Muscovites remained meekly deferential, more or less continuously, while they built up their own strength.

They could, however, dream of preeminence, under the Mongols,

over other Christian states in Russia. Muscovy’s great advantage was its central location, astride the upper Volga, controlling the course of the river as far as the confluence of the Vetluga and the Sura. The Volga was a sea-wide river, navigable almost all along its great, slow length. Picture Europe as a rough triangle, with its apex at the Pillars of Hercules. The corridor that links the Atlantic, the North Sea, and the Baltic forms one side; the linked waters of the Mediterranean and Black Sea form another. The Volga serves almost as a third sea, overlooking the steppes and forests of the Eurasian borderlands, linking the Caspian Road and the Silk Roads to the fur-rich Arctic forests and the fringes of the Baltic world. The Volga’s trade and tolls helped fill Ivan’s money bags and elevate Muscovy over its neighbors.

Rulership was ferociously contested, because the rewards made the risks seem worthwhile. In consequence, political instability racked the state and checked its ascent. For nearly forty years, from the mid-1420s, rival members of the dynasty fought each other. Vasily II, who became ruling prince at the age of ten in 1425, repeatedly renounced and recovered the throne, enduring spells of exile and imprisonment. He blinded his rival and cousin and suffered blinding in his turn when his enemies captured him: as a way of disqualifying a pretender or keeping a deposed monarch down, blinding was a traditional, supposedly civilized alternative to murder. When Vasily died in 1462, his son, Ivan III, inherited a realm that war had rid of internal rivals. Civil wars seem destructive and debilitating. But they often precede spells of violent expansion. They militarize societies, train men in warfare, nurture arms industries, and, by disrupting economies, force peoples into predation.

Thanks to the long civil wars, Ivan had the most efficient and ruthless war machine of any Russian state. The wars had ruined aristocrats already impoverished by the system of inheritance, which divided the patrimony of every family with every passing generation. The nobles were forced to serve the prince or collaborate with him. Wars of expansion represented the best means of building up resources and accumulating lands, revenues, and tribute for the prince to distribute. For successful

warriors, promotions and honors beckoned, including an enduring innovation: gold medals for valor. Nobles moved to Moscow as offices of profit at court came to outshine provincial opportunities of exploiting peasants and managing estates. Adventurers and mercenaries—including many Mongols—joined them. By the end of Ivan’s reign, an aristocracy of service over a thousand strong surrounded him.

A permanent force of royal guards formed a professional kernel around which provincial levies grouped. Peasants were armed to guard the frontiers. Ivan III set up a munitions factory in Moscow and hired Italian engineers to improve what one might call the military infrastructure of the realm—forts, which slowed adversaries, and bridges, which sped mobilization. He abjured the traditional ruler’s role of leading his armies on campaign. To run a vast and growing empire, ready to fight on more than one front, he stayed at the nerve center of command and created a system of rapid posts to keep in touch with events in the field. None of his other innovations seemed as important, to him, as improved internal communications. At his death, he left few commands to his heirs about the care of the empire, except for instructions about the division of the patrimony and the allocation of tribute; but the maintenance of the post system was uppermost in his mind: “My son Vasily shall maintain, in his Grand Princedom, post stations and post carts with horses on the roads at those places where there were post stations and post carts with horses on the roads under me.” His brothers were to do the same in the lands they inherited.

5

Backed by his new bureaucracy and new army, Ivan could take the step so many of his predecessors had longed for. He could abjure Mongol suzerainty. In the event, it was easy, not only because of the strength Ivan amassed but also because internecine hatreds shattered the Mongols’ unity. In 1430, a group of recalcitrants split off and founded a state of their own in the Crimea, to the west of the Golden Horde’s heartland. Other factions usurped territory to the east and south in Kazan and Astrakhan. Russian principalities began to see the possibilities of independence. Formerly, once the shock of invasion and conquest was

over, their chroniclers had accepted the Mongols, with various degrees of resignation, as a scourge from God or as useful and legitimate arbitrators, or even as benevolent exemplars of virtuous paganism whom Christians should imitate. Now, from the mid–fifteenth century, they recast them as villains, incarnations of evil, and destroyers of Christianity. Interpolators rewrote old chronicles in an attempt to turn Alexander Nevsky, who had been a quisling and collaborator on the Mongols’ behalf, into a heroic adversary of the khans.

6

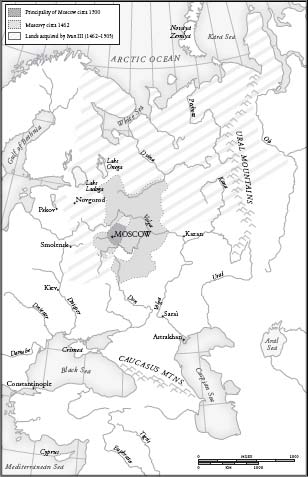

The expansion of Muscovy under Ivan III.

Ivan allied with the secessionist Mongol states against the Golden Horde. He then stopped paying tribute. The khan demanded compliance. Ivan refused. The horde invaded, but withdrew when menaced with battle—a fatal display of weakness. Neighboring states scented blood and tore at the horde’s territory like sharks at bloodied prey. The ruler of the breakaway Mongol state in the Crimea dispersed the horde’s remaining forces and burned Saray in 1502. Russia, the chroniclers declared, had been delivered from the Mongol yoke, as God had freed Israel from Egypt. The remaining Mongol bands in Crimea and Astrakhan became Ivan’s pensioners, for whom he assigned one thousand gold rubles at his death.

The Mongols’ decline liberated Ivan to make conquests for Muscovy on other fronts. From his father, Vasily II, he inherited the ambition, proclaimed in the inscriptions on Vasily’s coins, to be “sovereign of all Russia.” His conquests reflect, fairly consistently, a special appetite to rule people of Russian tongue and Orthodox faith. His campaigns against Mongol states were defensive or punitive, and his forays into the pagan north, beyond the colonial empire of Novgorod, were raids. But the chief enemy he seems always to have had in his sights was Casimir IV, who ruled more Russians than any other foreigner. How far Ivan followed a systematic grand strategy of Russian unification is, however, a matter of doubt. No document declares such a policy. At most, it can be inferred from his actions. He may equally well have been responding pragmatically to the opportunities that cropped up. But medieval rulers rarely planned for the short term—especially not when they thought

the world was about to end. Typically, they worked to re-create a golden past or embody a mythic ideal.

To understand what was in Ivan’s mind, one has to think back to what the world was like before Machiavelli. The modern calculus of profit and loss probably meant nothing to Ivan. He never thought about realpolitik. His concerns were with tradition and posterity, history and fame, apocalypse and eternity. If he targeted Muscovy’s western frontier for special attention, it was probably because he had the image and reputation of Alexander Nevsky before his eyes, refracted in the work of chroniclers who turned back to rewrite their accounts of the past, to burnish Alexander’s image, after a spell of neglect, and reidealized him as “the Russian prince” and the perfect ruler. Ivan did not initiate this rebranding, but he paid for chroniclers to continue it in his own reign.

Therefore, when Ivan began turning his wealth into conquests, he first tackled the task of reunifying the patrimony of Alexander Nevsky. Ivan devoted the early years of the reign to suborning or forcing Tver and Ryazan, the neighboring principalities to Muscovy’s west, into subordination or submission, and incorporating the lands of all the surviving heirs of Alexander Nevsky into the Muscovite state. But thoughts of Novgorod, where Alexander’s career had begun, were never far from his mind. Novgorod was an even bigger prize. The city lay to the north, contending against a hostile climate, staring from huge walls over the grain lands on which the citizens relied for sustenance. Famine besieged them more often than human enemies did. Yet control of the trade routes to the river Volga made Novgorod cash rich. It never had more than a few thousand inhabitants, yet its monuments record its progress: its kremlin, or citadel, and five-domed cathedral in the 1040s; in the early twelfth century, a series of buildings that the ruler paid for; and, in 1207, the merchants’ church of St. Paraskeva in the marketplace.

From 1136, communal government prevailed in Novgorod. The revolt of that year marks the creation of a city-state on an ancient model—a republican commune like those of Italy. The prince was deposed for reasons the rebels’ surviving proclamations specify: “Why did he not

care for the common people? Why did he want to wage war? Why did he not fight bravely? And why did he prefer games and entertainments rather than state affairs? Why did he have so many gyrfalcons and dogs?” Thereafter, the citizens’ principle was: “If the prince is no good, throw him into the mud!”

7

To the west, Novgorod bordered the small territorial domain of Russia’s only other city-republic, Pskov. There were others again in Germany and on the Baltic coast, but Novgorod was unique in eastern Europe in being a city-republic with an extensive empire of its own. Even in the West, only Genoa and Venice resembled it in this respect. Novgorod ruled or took tribute from subject or victim peoples in the boreal forests and tundra that fringed the White Sea and stretched toward the Arctic. Novgorodians had even begun to build a modest maritime empire, colonizing islands in the White Sea. The evidence is painted onto the surface of an icon, now in an art gallery in Moscow but once treasured in a monastery on an island in the White Sea. It shows monks adoring the virgin on an island adorned with a golden monastery with tapering domes, a golden sanctuary, and turrets like lighted candles. The glamour of the scene must be the product of pious imaginations, for the island in reality is bare and impoverished and surrounded, for much of the year, with ice.

Pictures of episodes from the monastery’s foundation legend of the 1430s, about a century before the icon was made, frame the painter’s vision of the Virgin receiving adoration. The first monks row to the island. Young, radiant figures expel the indigenous fisherfolk with angelic whips. When the abbot, Savaatii, hears of it he gives thanks to God. Merchants visit. When they drop the sacred host that the holy monk Zosima gives them, flames leap to protect it. When the monks rescue shipwreck victims, who are dying in a cave on a nearby island, Zosima and Savaatii appear miraculously, teetering on icebergs, to drive back the pack ice. Zosima experiences a vision of a “floating church,” which the building of an island monastery fulfils. In defiance of the barren environment, angels supply the community with bread, oil, and salt.

Whereas Zosima’s predecessors as abbots left because they could not endure harsh conditions, Zosima calmly drove out the devils who tempted him. All the ingredients of a typical story of European imperialism are here: the more than worldly inspiration; the heroic voyage into a perilous environment; the ruthless treatment of the natives; the struggle to adapt and found a viable economy; the quick input of commercial interests; the achievement of viability by perseverance.

8

Outreach in the White Sea could not grasp much or get far. Novgorod was, however, the metropolis of a precocious colonial enterprise by land among the herders and hunters of the Arctic region, along and across the rivers that flow into the White Sea, as far east as the Pechora. Russian travelers’ tales reflected typical colonial values. They classed the native Finns and Samoyeds of the region with the beast men, the

similitudines hominis,

of medieval legend. The “wild men” of the north spent summers in the sea lest their skin split. They died every winter, when water came out of their noses and froze them to the ground. They ate each other and cooked their children to serve to guests. They had mouths on top of their heads and ate by placing food under their hats; they had dogs’ heads or heads that grew beneath their shoulders; they lived underground and drank human blood.

9

They were exploitable for reindeer products and fruits of the hunt—whale blubber, walrus ivory, the pelts of the arctic squirrel and fox—that arrived in Novgorod as tribute from the region and were vital to the economy.