A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy (35 page)

Read A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy Online

Authors: Eric Lamet

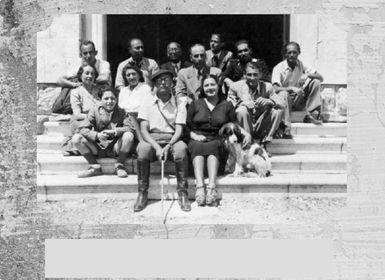

The steps to the entrance of the altar in Montevergine.

Finished eating, I pestered the people to pose for a number of group photographs. I remembered little of how to use the camera, but my enthusiasm compensated for my lack of knowledge. Everyone was in a happy mood, and no one complained that I made them stand, sit, then stand again. Taking pictures and seeing new sights had me so engrossed that I forgot why we had made the climb. Only on our way back to Ospedaletto did my sadness return. Not even my shiny new watch was of any solace.

As I was kicking up dust on the narrow path, Pietro caught up with me and placed his arm around me. “What goes?”

I struggled out of his friendly hold. “Nothing.”

“Eh, I know you too well. Something is bothering you.”

“Leave me alone,” I shouted.

I was brusque. He didn't deserve my rude reaction, but I was angry and couldn't help but feel that, just as my papa had done before, Pietro was abandoning me. I was only twelve, just a boy, yearning for that special paternal love.

Drowning in my misery, I trotted all the way down to Ospedaletto, crying and kicking stones.

Back in the village, I raced across the municipal gardens and up our two flights to take refuge in Mother's room. My room was too accessible and, the way I felt, I didn't want to see anyone. I turned the key to lock the door and threw myself onto the bed. Not long after I heard a faint knock followed by Pietro's gentle voice. I unlocked the door and kept it ajar and his large and friendly face, with that captivating smile, peeked through the narrow opening.

“Can we talk?” he asked.

I made some kind of noise in response and fell back on the bed.

He pushed open the door, entered and sat next to me. “I would like to know what's bothering you.”

It was impossible to resist his love-filled voice. I buried my face into his chest and wept out loud. “Will I ever see you again?”

Group of internees who climbed to Montevergine to celebrate Pietro Russo's release from internment in June 1942.

With his strong arms around me and his large hand gently stroking my hair, he shared his gentleness with me. “Of course you'll see me again. I love you and I love your mother.” It was the first time I had heard Pietro express this feeling. Love. What a warm, beautiful word! What splendid emotion! At that moment I could only think of the word but didn't quite grasp its full meaning.

Four more days before Pietro would leave, us and of those days I tried to steal as many of the hours as he and Mamma would allow. I even spent one night in his room, something I had done occasionally.

“Do you remember the night when you showed off how you could hit the ceiling with your spit?” I asked.

“Of course, I remember. I also remember how cold it was and the brazier we placed between the sheets didn't do much to keep us warm. We did such silly things just to keep our blood flowing.”

“I like when you read Pirandello. I'll miss that much more than the spitting contest.” We both laughed. Not a happy laughter.

“I'll read to you tomorrow. When I get home, I'll send you an anthology of Italian poetry and you'll be able to read them by yourself.”

“It won't be the same.”

The next morning Pietro found a volume of poetry. I watched how gently he fondled that book. He loved Italian literature and had a unique fondness for Carducci, Foscolo, and Leopardi.

Partially from the open book held in one hand but mostly from memory, Pietro recited the words of a grieving father: “

Sei nella terra fredda

,

sei nella terra negra

,

ne il sol piú ti rallegra

,

ne ti risveglia amor

.”

My eyes were swollen as I shared in the pain and anguish of the poet Carducci, who had penned the verses for his dead child. The day before leaving us,

Pupo

gave me that book of poetry. I have reread those same verses many times but never recaptured the feelings Pietro created with his reading.

Tragedies and Grief

S

ince the start of the war, death occurred frequently in Ospedaletto. Most adult males had been drafted into Mussolini's army and, some of the internees remarked, if luck was on their side, they were sent to Africa; otherwise, they were shipped to the Russian front. As young men turned eighteen, they were drafted, stirring up emotions in their respective households. But the news of a soldier killed or missing in action caused hysteria among parents, relatives, and friends, bringing misery and sorrow to the entire village. Most of the 1,800 townspeople were related to one another by blood, by marriage, or by being a

cummare

.

To an acquaintance, who grieved a recent loss, I asked, “What is a

cummare

?”

“A

cummare

?” She hesitated a bit. “He was our best man when I got married. It could be someone who helped name your baby or just a good friend.”

In a village where grief became a public spectacle and death a frequent visitor, war caused much visible agony. I remember well the large, disheveled woman, clad in black, a large cross swinging from her neck and dirty hair slipping out from under her black scarf, who came running from her home, arms waving over her head. She stopped, looked up and down the narrow road, then, as loud as any human lungs allowed, cried out the terrible news. “

Maronna mia

!

Hanno ammazzato Peppino

.”

Because half the men in Ospedaletto d'Alpinolo were nicknamed Peppino, bedlam erupted in every family, whether they had a soldier by that name or not. It followed that, as the woman's howling spread the news of Peppino's death, a mob frenzy engulfed the village, piercing the placid mountain air with distraught screams.

“Which Peppino?” someone shouted.

“Maria's son.” Not much help, since Ospedaletto had as many Marias as Peppinos. The mass wailing increased, spreading down the dusty road, to the narrow alleyways and into every home. I kept turning in the direction of the new sounds and, if not for the tragedy of the moment, I might have been witnessing a well-rehearsed

opera buffa.

During a similar episode, I discovered how contagious weeping could be. Several women, in the same black attire with crosses hanging from their necks, emerged from their homes and joined in the communal wailing. I got the impression that sobbing could only be performed in public or, possibly, that no one wanted so much noise inside their own house.

These open displays of grief became more frequent as the fortunes of war turned against Italy.

In the fall of 1942, I went to visit the postmaster's twenty-year-old son, Carmine, who lay dying of tuberculosis. Though I was much younger, I had befriended him and wanted to pay him a last visit.

“I don't want you to get too close to him,” Mamma admonished me. “TB is very contagious. I let you go because it's the right thing to do.”

When I went to the apartment above the post office and entered Carmine's room, I found his parents, Don Guglielmo and his wife, by his side. I kept a distance from the bed as I had promised my mother and thus was unable to hear the dying young man's soft whispers. His father conveyed the message that he was grateful for my visit.

On that same day, a telegram from the Ministry of Defense arrived with news that the dying young man's older brother had been killed at the Russian front. In a compassionate gesture, the mailman, acting as assistant postmaster, kept the telegram from the grief-stricken parents for several months.

Each new tragic announcement from the defense department created absolute havoc for Dora Dello Russo. Antonio had been shipped to occupied Albania and, though he wrote frequently, his letters were more than a week old by the time they arrived.

“Lotte, I'm going mad. Men are dying everywhere. If anything happens to Totonno, I'll kill myself.” Dora no longer spoke. She only shouted.

“And you'll leave your children orphans? That is really clever. Nothing is going to happen to Antonio. I feel it inside. Nothing. Do you hear me?”

I loved listening to my mother talk. Her soothing melodic voice calmed Dora. I admired Mamma's talent to put words together. They simply flowed. But I never understood how she could be so certain of her almost psychic premonitions.

Lello Is Born

L

ello Dello Russo was born in the winter of 1942, and showing how much confidence she had in my mother, Dora encouraged her to share in the care of the newborn.

Since Pietro's departure in June, Mother had shown little interest in anything. Even her contact with other internees had been reduced to a bare minimum. Knowing how much she thrived on interacting with people, I was disturbed to watch her become a recluse. Lello's birth was the event Mother needed. She soon became involved with the new baby and, when I saw how her spirits were lifted, I realized that Lello's arrival was a truly blessed event for us all.

Mamma began wearing dresses she had not worn in months and cooking more elaborate meals. Everything about her spoke of the pleasure she took in sharing Dora's maternal duties. Perhaps at one time in her life my mother might have wanted more children, although she had never openly expressed that desire. As for me, a brother or a sister would have been a welcome comfort in those trying days but, for whatever reason, no other children ever enriched our family.

During our first days in Ospedaletto, Mamma had noticed the practice of swaddling children before they were put to bed. Frowning, she had mumbled, “How barbarous. Have these women never heard of diapers?”

On the evening when I watched Filomena, our landlady, wrap her baby's feet, legs and buttocks in an endless binding and turn the child into an inflexible living mummy, I had described the incident to

Mutti

.

“How long do they keep a child in this inhumane state?” Mamma asked Dora, after having watched the thirty-month-old child being bandaged for the night.

“Until the child learns to use the toilet.”

Mother looked horrified. She shook her head in disbelief, as though the shaking could bring a better understanding of what she had heard. “Even if the baby learns to tell you it has to go, by the time you unravel these

fasce

, the child will no longer need a toilet. Besides, I wouldn't be surprised if the stench in what you call a toilet will not make the child wish to stay wrapped forever.”

Nothing could change the old ingrained habits and customs in Ospedaletto d'Alpinolo.

Observing a woman breastfeeding an older child, my Mamma asked, “How old is he?”

“Three.”

I knew my mother well enough to recognize the meaning of her facial expression. Mamma was outraged. Her grimaces were more expressive than a hundred words. I often told her she should have been an actress. On another occasion I was baffled to see a child, who had been playing in the street, run up to his mother, unbutton her dress and cling to her breast. The boy seemed even older than three. Nor was it uncommon to see a woman, sitting on her front steps, with two children of different ages busily sucking from her fully exposed breasts.

Once my mother asked a woman how long she breastfed her children.

“It depends,” the woman replied. “I still nurse the last three.”

To Dora Mother said, “You know how I feel about

fasce

and breastfeeding. If you want me to help, it has to be my way.”

“I'll try. Whatever you say, Lotte.”

So, at age forty-one and without giving birth, my mother became Mamma Lotte for the Dello Russos and practiced her earned title for the remainder of our stay in Ospedaletto. Reluctantly, Dora stopped breastfeeding when Lello was six months old.

“I stopped when Enrico was six months. Look how healthy he is now,” Mamma said.

Lello was never bandaged and, instead of

fasce

, my mother introduced Dora to more modern methods. “I need a sheet to make diapers for Lello.”

No one in Ospedaletto had ever heard of diapers and Dora was no exception. Nonetheless, she gave Mother everything she asked for.

Except for breastfeeding, Mamma Lotte performed with enthusiasm most other maternal roles. I also enjoyed the presence of that little fellow and never felt jealous of the attention we now shared. For me, Lello was the baby brother I never had, although it occurred to me that the fraternal relationship was only for the duration of our stay. Mamma was so devoted to her new charge that, during Lello's first two months, she even abandoned her regular bridge game. Caring for the baby was great therapy for her lonely heart.

When Antonio was discharged from the army for medical reasons in December 1942 and went back to his commercial activities, most stores had empty shelves and welcomed any merchandise anyone was able to deliver. Antonio earned more than the family could spend.

With both Dora and Antonio, Mother shared what she had experienced at the end of the first Great War. “You must take your money and buy things. Buy anything. It doesn't matter what. All your money will not be enough to buy one pound of bread. After the last war, people carried their money in wheelbarrows to buy just one small bag of potatoes. Paper money had so many zeros, people didn't know how much it was worth.”