Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

All the King's Cooks (22 page)

The tables were so crowded that the servants frequently spilled broth, liquor or fat over the diner’s clothes and hats, as they reached over them to put dishes on the table. Then, instead of observing gentlemanly reserve, everyone would dig in:

17

If the dish is pleasant, either flesh or fish,

Ten hands at once swarm in the dish.

And if it be flesh, ten knives shalt thou see

Mangling the flesh and in the platter flee:

To put there thy hands is peril without fail,

Without a gauntlet or else a glove of mail.

Amongst all these knives thou one of both must have,

Or else it is hard thy fingers whole to save:

Oft in such dishes in court is seen,

Some leave their fingers, each knife is so keen.

On finger gnaweth some hasty glutton,

Supposing it is a piece of beef or mutton …

There was good reason for this haste, for although,

18

Slowe be the servers in serving in alway,

But swift be they after taking meat away.

A special custom is used them among,

No good dish to suffer on board to be long.

The hungry servers which at the table stand

At every morsel hath eye unto thy hand …

Because that thy leavings is only their part,

If thou feed thee well, sore grieved is their heart;

Namely of a dish costly and daintious,

Each piece that thou cuttest to them is tedious.

Then at the cupboard one doth another tell

‘See how he feedeth, like a devil of Hell,

Our part he eateth, nought good shall we taste’,

Then pray to god it will be thy last.

The serving of ale caused similar problems. It was brought up from the great buttery by the yeomen of the pitcher house in leather jugs, which cost £5 a year in replacements.

18

Each mess received twelve pints per meal each meat day (six pints per man per day), and eight pints per meal on fish days (or four pints per man per day). It was poured out into wooden cups, these being shaped like open bowls rather than as modern cups. Turned from tough ash, they cost £20 a year in replacements. Each morning the yeomen and page of the pitcher house had to retrieve all those that had been used to serve liveries to bedchambers the previous night, carefully counting them to ensure that there were sufficient to serve the Hall.

19

Some smaller cups, perhaps holding about a pint, were used individually, but most people appear to have shared a common drinking bowl to each mess, which even then was considered unsavoury as well as unfair – anyone calling for more ale if their bowl had been drained by others was called ‘malapart or dronke, or an abbey lowne [worthless, idle monk], or limnier [manuscript illuminator] of a monke’. By repute, the cups were scoured only once a year, being merely swilled at other times. Not surprising, then, that they appeared:

20

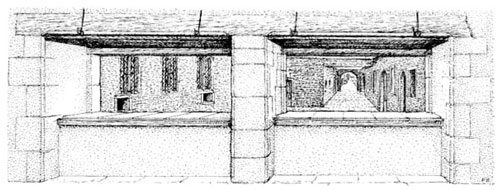

44.

The Buttery bar

With typical attention to good housekeeping, the cellar staff within the buttery were kept separate from the pitcher house staff who carried up the ale and wine and served it, thus ensuring that there was little opportunity for unauthorised consumption.

Old, black and rusty, lately taken from some sink:

And in such vessel drink thou often time,

Which in the bottom is full of filth and slime,

And in that vessel thou drinkest oft I wis,

In which some states [important men] or dames late did piss.

But for those who dined here every day such matters would have been of little concern, for theirs was a canteen culture of the most robust kind. Once they had finished, got up, washed and returned to their duties, the servers would dine on the left-overs and whatever they had managed to put to one side, then carry all the dishes and tableware down to the hatches in the pewter scullery wall, by the hall-place dresser office (no. 34). Any remaining food would go into the almonry here (no. 55), and then be taken to the poor waiting at the gate of the Outer Court, where it had arrived fresh and raw perhaps a day, or even a matter of hours, before.

45.

The Hall-place dresser

When dinner was served, every dish would be taken from these hatches, carried to the dresser-office hatch to the immediate right, and then up into the Great Hall. On return, the waste food was deposited in the Almonry directly ahead, and the dishes and so forth passed into the pewter scullery through the square hatches on the left, all under the watchful eyes of the clerks in the dresser office.

Although noteworthy textual research was undertaken by a number of mid-Victorian scholars, it is only in recent years that historic kitchens and domestic management have begun to be studied in any detail, and only now that the sophistication of their design and administration is being slowly revealed. In the Tudor kitchens at Hampton Court we find a domestic organisation that is both conceptually and physically second to none. Not only are they the finest kitchens of their period, but they are the largest, most intact and best documented of all Britain’s early industrial buildings – a virtually faultless management scheme realised in brick, stone and timber. If the opportunity arises, go and see them for yourself, following the public route through to the Back Gate, and on towards the dressers, observing how each building, door, window and fireplace has been arranged for maximum efficiency. Then move on to the Great Hall and the Great Watching Chamber, and see where the dinners and suppers were served in interiors of the greatest magnificence. It is a truly incomparable experience.

The Recipes

A Practical Approach to Tudor Food

The best source of information regarding the food cooked in the palace’s various kitchens are the Eltham Ordinances of 1526. These provide a priced list of all the individual dishes served to the king and queen and to each rank of courtier and the household servants on both meat and fish days. For those of the highest status there were two courses for both dinner and supper, each course having up to seventeen different dishes placed on the table, from which the diners might choose whatever they liked. Each type of dish was taken in its well-established sequence. The first course commenced with pottages, then a selection of mainly boiled foods, followed by custards, tarts, fritters or fruit. The second course might also start with a further pottage, before moving on to rather more delicate roasts and baked dishes, again finishing with tarts, fritters and fruit.

Suggested Bill of Fare for the King, Queen and

Courtiers Dining in the Chamber

Meat Day | Fish Day |

First Course

Pottages: A Good Pottage | Pottage in Lent |

Gruel of Force | |

Venison in Bruet, with Frumenty | Stewed Herring |

Stew of Flesh | Salt Fish in Sauce |

Alloes of Beef | Calver Salmon |

Stewed Mutton Steaks | Fried Whiting |

Stewed Leg of Lamb with cloves Haddock | |

Stewed Capon | Stewed Plaice |

Capon in Douce | Trout |

Smothered Rabbit | Crab |

Cabbage | Cabbage |

Rice of Genoa | Rice of Genoa |

Garnished Custard | Custard |

Spinach Fritters | Spinach Tart |

Apple Fritters |

Second Course

Pottages: Jelly Ipocras | Eel Pottage |

Cream of Almonds | |

Roast Pheasant | Sturgeon |

Roast Venison | Roasted Salmon |

Venison Pie | Mortress of Fish |

Peacock Royal | Crayfish |

with Sauce Ginger | Shrimps |

Roast Chicken, Farced | Blancmange of Fish |

Chicken Pie | Stewed Leeks |

Boiled Onions | Peas Royal |

Buttered Worts | Gooseberry Tart |

Cheese Tart | Curd Fritters |

Apple Fritters | Roast Pippins |

Roast Oranges |

Confectionery for their Sweetmeat Banquets

This probably included:

Prunes in Syrup | Kissing Comfits or |

Conserve of Cherries | Muscadines |

Succade of Lemon Peels | Cards |

Marmalade of Lemons & Oranges | Cinnamon Sticks |

Marmalade of Peaches or Apricots | Walnuts |

Marchpanes | White Gingerbread |

Sugar Plate (Boiled) | Court Gingerbread |

Sugar Paste (Paste) | Comfits |

Hippocras |

The quality, expense and variety of these dishes stands in great contrast to that of the basic fare offered to the household servants. This was certainly substantial and sustaining, but must have been extremely boring to those who received it day after day, year on year. However, as with every other aspect of Hampton Court, it served its purpose in establishing exactly where everyone stood in the court’s hierarchy.

Bill of Fare for Servants in the Great Hall

Meat Day | Fish Day |

First Course

Pottage with Whole Herbs | Pottage for Lent |

Second Course

Dry- or Wet-salted Beef | Boiled, salt or |

Lombard Mustard | Broiled Fish |

The following recipes for making most of the above dishes have all been taken from historical recipe books, but have had their quantities reduced to suit modern circumstances. Since all have been practically tested at the palace, additional details such as oven temperatures, modern weights and measures have been added, all references to teaspoons and table spoons being for their

level, not heaped, contents. Other adaptations have been made to enable the dishes to be cooked in the modern kitchen, replacing spit-roasting with oven-roasting, for example, or grinding in a food-processor rather than in a stone mortar. Despite these changes in technique, the combination of the recipes with good quality organic produce still gives a range of really excellent dishes. They may be used to create complete Tudor feasts, but are just as appropriate for ordinary dinner parties and family meals, their appearance, flavours, textures and scents being more than adequate to compete with any of today’s multi-cultural cuisines.

Meat Day First Course Pottages

A GOOD POTTAGE

2

900g (2lb) rolled beef, brisket | 60ml (4 tbs) finely |

or lamb | chopped herbs |

8 spring onions | chosen from parsley, |

5ml (1tsp) salt | spinach, endive |

60ml (4 tbs) medium oatmeal | strawberry leaves, |

violet leaves, succory | |

(chicory) and | |

marigold petals. |