Read Antony and Cleopatra Online

Authors: Colleen McCullough

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Historical Fiction, #Historical, #Romance, #Antonius; Marcus, #Egypt - History - 332-30 B.C, #Biographical, #Cleopatra, #Biographical Fiction, #Romans, #Egypt, #Rome - History - Civil War; 49-45 B.C, #Rome, #Romans - Egypt

Antony and Cleopatra (80 page)

Late that night, a little tipsy—it had been a harrowing month—Octavian stood back to let his valet pull the covers down so he could climb into bed. There, coiled in the middle of it, was seven feet of cobra as thick as a man’s arm. Octavian screamed.

ETAMORPHOSIS

29 B.C. to 27 B.C.

When Cleopatra’s three living children embarked for Rome in the care of the freedman Gaius Julius Admetus, they sailed alone; like Divus Julius when he had left Egypt, Octavian decided he may as well tidy up Syrian Asia and Anatolia before returning to Rome. A stipulated amount of the gold he had sent to the Treasury was to be sold to buy silver for minting into denarii and sesterces: neither too much nor too little. The last thing Octavian wanted was inflation after so many years of depression.

A wearisome business, my sweetest girl, yet I feel you will approve of my logic; yours is its only rival. Store your desires in a place you will not forget, have them ready for me when I come home. Not for many months, alas. If I settle the East properly, I need not return there for years.

It is hard to credit that the Queen of Beasts is dead and in her tomb, there to be reduced to an effigy made out of what looks like Pergamum parchment glued together. Similar to the puppets people so love when the traveling shows come to town. I saw some mummies in Memphis, all bandaged up. The priests weren’t happy when I commanded them to unwrap the things, but obeyed because they were not of the highest class of dead. Just a wealthy merchant, his wife, and their cat. I can’t decide whether it is the muscle that wastes away, or the fat that melts away. One or the other does, leaving the face fallen in, as happened to Atticus. One does see that it is the relic of a human being, and can make assumptions about character, beauty, et cetera. I am bringing some of these mummies to Rome and will display them on a float in my triumphal parade, together with a few priests so that the People can see every stage of the gruesome process. The Queen of Beasts is welcome to this fate, but the thought of Antonius chews at me. Undoubtedly it is a mummified Marcus Antonius who has stimulated such fascination among those of us who were in Egypt. Proculeius tells me that Herodotus described the business in his treatise, but as he wrote in Greek, I never read him myself: not on a schoolboy’s syllabus.

I have left Cornelius Gallus to administer Egypt as

praefectus

. He’s very pleased, so much so that the poet has vanished, temporarily at least. All he can talk about are the expeditions he wants to make—south into Nubia and beyond that to Meroë—west into the eternal desert. He is also convinced that Africa is a mighty island, and intends to sail right around it in Egyptian ships that are built to go to India. I don’t mind these giddy essays into exploration, as they will keep him busy. Far rather them, than learn he has spent his time sniffing around Memphis in search of buried treasure. The affairs of the country have been well taken care of by a team of officials I personally chose.This comes to you with Cleopatra’s young children, a ghastly trio of miniature Antonii with a dash of Ptolemy. They need heavy discipline that Octavia won’t be prepared to administer, but I’m not worried. A few months living with Iullus, Marcellus, and Tiberius will tame them. After that, we shall see. I hope to marry Selene to a client-king when she’s grown, whereas the boys present a more difficult problem. I want all memory of their origins erased, so you are to tell Octavia that Alexander Helios will henceforth be known as Gaius Antonius, and Ptolemy Philadelphus as Lucius Antonius. What I hope is that the boys are on the dull side. As I am not confiscating Antonius’s properties in Italia, Iullus, Gaius, and Lucius will have a decent income. Luckily so much was cashed in or sold that they will never be hugely rich and therefore a danger to me.

Only three of Antonius’s marshals were executed. The rest are nothings, grandsons of famous men long dead. I pardoned them on condition that they swore the oath to me in a slightly modified form. Which is not to say that their names won’t go down on my secret list. An agent will be assigned to watch each of them, certainly. I am Caesar, but no Caesar.

As to your request to have some of Cleopatra’s clothing and jewelry, my dearest Livia Drusilla, all of it will come to Rome, but to be displayed in my triumph. Once that is over, you and Octavia may choose some items that I will buy for you, thus ensuring that the Treasury is not cheated. There will be no more sticky fingers.

Keep well. I will write again from Syria.

From Antioch Octavian went to Damascus, and from there sent his ambassador to King Phraates in Seleuceia-on-Tigris. The man, a pretender to the Parthian throne named Arsaces, was loath to put his head back inside the lion’s jaws, but Octavian was adamant. As Syria held Roman legions from one end to the other, Octavian was sure the King of the Parthians would do nothing foolish, including harming the Roman conqueror’s ambassador.

So as winter began at the end of that year when Cleopatra’s dreams had died, Octavian met with a dozen Parthian noblemen in Damascus and hammered out a new treaty: everything east of the Euphrates River to be in the domain of the Parthian Empire, and everything west of the Euphrates to be in the domain of the Roman Empire. Armed troops would never cross that mighty body of milky blue water.

“We had heard that you were wise, Caesar,” said the chief Parthian ambassador, “and our new pact confirms it.”

They were strolling the fragrant gardens for which Damascus was famous, an incongruous couple: Octavian in a purple-bordered toga; Taxiles in a frilly skirt and blouse, a series of gold rings around his neck, and a little round brimless hat encrusted with ocean pearls upon his corkscrewed black locks.

“Wisdom is mostly common sense,” said Octavian, smiling. “I have had a career so checkered that it would have foundered dozens of times were it not for two things—my common sense and my luck.”

“So young!” Taxiles marveled. “Your youth fascinates my king more than anything else about you.”

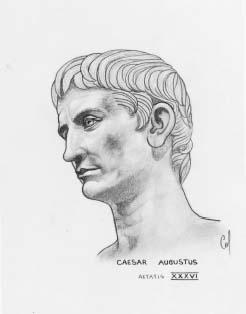

“Thirty-three last September,” said Octavian rather smugly.

“You will be at the head of Rome for decades to come.”

“Definitely. I hope I can say the same for Phraates?”

“Just between you and me, Caesar, no. The court has been in turmoil since Pacorus invaded Syria. I predict that there will be many Kings of Parthia before your reign ends.”

“Will they adhere to this treaty?”

“Yes, categorically. It frees them to deal with pretenders.”

Armenia had fallen away since the war of Actium took place; Octavian started the exhausting journey up the Euphrates to Artaxata, fifteen legions following him on what seemed to some of the soldiers to be a march they were doomed to repeat forever. But this was to be the last time.

“I have handed responsibility for Armenia to the King of the Parthians,” Octavian said to Artavasdes of Media, “on condition that he stays on his side of the Euphrates. Your part of the world is shadowy because it lies north of the Euphrates headwaters, but my treaty fixes the boundary hereabouts as a line between Colchis on the Euxine Sea and Lake Matiane. Which gives Rome Carana and the lands around Mount Ararat. I am returning your daughter Iotape to you, King of the Medes, for she should marry a son of the King of the Parthians. Your duty is to keep the peace in Armenia and Media.”

“And all done,” said Octavian to Proculeius, “without loss of life or limb.”

“You need not have gone to Armenia in person, Caesar.”

“True, but I wanted to see the lie of the land for myself. In years to come when I am sitting in Rome, I may need to have firsthand knowledge of every eastern land. Otherwise some new military man hungry for fame might hoodwink me.”

“No one will ever do that, Caesar. What will you do with all the client-kings who sided with Cleopatra?”

“Not demand money from them, for sure. If Antonius hadn’t tried to tax these people money they just do not have, things might have turned out very differently. Antonius’s dispositions themselves are excellent, and I can see no merit in overturning them simply to assert my own might.”

“Caesar’s a puzzle,” said Statilius Taurus to Proculeius.

“How so, Titus?”

“He doesn’t behave like a conqueror.”

“I don’t believe he thinks of himself as a conqueror. He’s simply fitting together the pieces of a world he can hand to the Senate and People of Rome as finished, complete in every way.”

“Huh!” Taurus grunted. “Senate and People of Rome, my arse! He has no intention of letting go the reins. No, what puzzles me, old chap, is how he intends to rule, as rule he must.”

He was holding his fifth consulship when he pitched camp on the Campus Martius accompanied by his two favorite legions, the Twentieth and the Twenty-fifth. Here he was obliged to stay until he had celebrated his triumphs, three all told: for the conquest of Illyricum, for victory at Actium, and for the war in Egypt.

Though none of the three could hope to rival some of the triumphs of the past, each of them far outstripped any predecessors when it came to propaganda. His pageant Antonys were shambling oafs of elderly gladiators, his Cleopatras gigantic German women who controlled their Antonys with dog collars and leashes.

“Wonderful, Caesar!” said Livia Drusilla after the triumph for Egypt was over and her husband came home from the lavish feast in Jupiter Optimus Maximus.

“Yes, I thought so,” he said complacently.

“Of course some of us remembered Cleopatra from her days in Rome, and were amazed at how much she’d grown.”

“Yes, she sucked Antonius’s strength and elephanted.”

“What an interesting verb!”

Then came the work, which was what Octavian loved the most. He had departed from Egypt the owner of seventy legions, an astronomical total that only gold from the Treasure of the Ptolemies enabled him to retire comfortably. After careful consideration he had decided that in future Rome needed no more than twenty-six legions; none of them was to be stationed in Italia or Italian Gaul, which meant that no ambitious senator of a mind to supplant him would have troops conveniently close by. And at last these twenty-six legions were to constitute a standing army that would serve under the Eagles for sixteen years and under the flags for a further four years. Each of the forty-four legions he discharged was disbanded and scattered from one end of Our Sea to the other, on land confiscated from towns that had backed Antony. These veterans would never live in Italia.

Rome herself began the transformations Octavian had vowed: from brick to marble. Every temple was repainted in its proper colors, the squares and gardens were beautified, and the plunder from the East was dispersed to adorn temples, forums, circuses, marketplaces. Wondrous statues and paintings, fabulous Egyptian furniture. A million scrolls were to be put in a public library.

Naturally the Senate voted Octavian all kinds of honors; he accepted very few, and disliked it when the House persisted in calling him

“dux”

—leader. Secret hankerings he had, but they were not of a blatant nature; the last thing he wanted was to look a naked despot. So he lived as befitted a senator of his rank, but never flamboyantly. He knew he couldn’t continue to rule without the connivance of the Senate, yet he knew just as certainly that somehow he had to draw that body’s teeth without seeming to have grown any himself. It was a help to control the fiscus and the army, two powers he had no intention of laying down, but they did not endow him with a shred of personal inviolability. For that, he needed the powers of a tribune of the plebs—not for a year or a decade, but for life. To that end he had to work, gradually accruing them until finally he had the greatest one of all—the power of the veto. He, the least musical of all men, had to sing the senators a siren song so seductive they would lie on their oars forever.

When Marcella turned eighteen she married Marcus Agrippa, consul for the second time; she hadn’t fallen out of love with her dour, uncommunicative hero, and entered the union convinced that she would captivate him.

Octavia’s nursery never seemed to diminish in size, despite the departure of Marcella and Marcellus, her two eldest. She had Iullus, Tiberius, and Marcia, all aged fourteen; Cellina, Selene, Selene’s twin the newly named Gaius Antonius, and Drusus, all twelve; Antonia and Julia, eleven; Tonilla, nine; the newly named Lucius Antonius, seven; and Vipsania, aged six. Twelve children altogether.

“I am sorry to see Marcellus go,” Octavia said to Gaius Fonteius, “but he has his own house and should take up residence in it. He is to be a

contubernalis

on Agrippa’s staff next year.”