Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (14 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Imagination expands human hunger

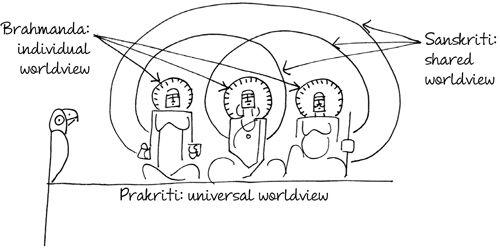

Humans have full power over their imagination. We can expand, contract and crumple it at will. This makes each individual a Brahma, creator of his/ her own subjective reality, the brahmanda, which literally means the 'egg of Brahma'.

We can choose what we want to see. We can choose what we want to value. Animals and plants do not have this luxury. They are fettered by their biology. They cannot be punished for hurting humans (though we often do); but humans can be punished for hurting other humans. Imagination liberates us from submitting to our instincts. We are, whether we like it or not, whether we are aware of it or not, responsible for our actions.

Prakriti or nature does not care much for human imagination, and expects humans to fend for themselves just like other animals. As far as nature is concerned, humans deserve no special treatment, much to Brahma's irritation. They, too, must struggle to survive.

In his imagination, Brahma sees the whole world revolving around him. So Brahma works towards establishing sanskriti or culture where the rules of nature are kept at bay, and rules from his brahmanda are realized. Sanskriti is all about creating a world where might is not right, where even the unfit can survive.

In sanskriti, Brahma encounters the brahmanda of other Brahmas, and he either battles them to enforce his rules, or bears the burden of their rules.

Brahma, thus, inhabits three worlds or tri-loka:

- Nature or prakriti

- Imagination or brahmanda

- Culture or sanskriti

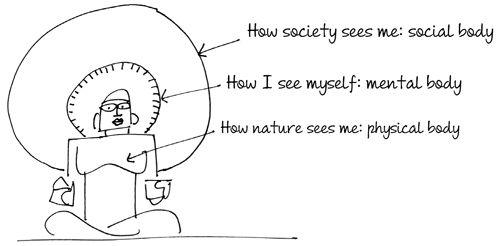

There are as many brahmandas as there are people, as many sanskritis as there are organizations and communities; but only one prakriti. Each of these worlds grant Brahma a body:

- Physical body or sthula-sharira, granted by prakriti.

- Mental body or sukshma-sharira, designed by brahmanda

- Social body or karana-sharira, created by sanskriti.

A good illustration of the three bodies is the character of Ravan from the Ramayan. He is born with ten heads and twenty arms, which constitute his sthula-sharira. Society recognizes him as a devotee of Shiva and king of Lanka, which constitute his karana-sharira. His desire to dominate, be feared and respected by everyone constitutes his sukshma-sharira.

In contrast to him is Hanuman, a monkey of immense strength (sthulasharira) who is content to be seen as the servant of Ram (karana-sharira), who does not seek to dominate and would rather seek meaning by helping the helpless Ram without seeking anything in return (sukshma-sharira).

While animals need food to nourish only their physical body, humans also need sustenance for their mental and social bodies. Animal movements are governed by feeding and grazing, human choices are governed by desire for wealth, power, fame, status and recognition. The purpose of yagna is to satisfy every human hunger. Failure to satisfy these hungers transforms the workplace into a rana-bhoomi.

Balwant is a tall man who has always been good with numbers. But his father could not send him to school beyond the fourth standard and he was forced to work in a field. Balwant imagines himself as a leader of men and so he migrated to the city looking for opportunities to prove his worth. Currently he works as a doorman in a building society, a job he got because of his commanding height. Everyone notices his height and uniform. Thus, they are able to identify his role and his status in society. A few observe how good he is with numbers. Hardly anyone notices that he loves to dominate those around him. As a result no one understands why he gets irritated when members of the building society order him around. They feel he is lazy and arrogant. They see his physical body and his social body, not his mental body.

Only humans can exchange

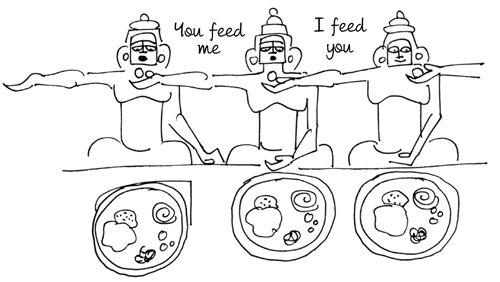

There is always more hunger than food. The Upanishads tell the story of how Brahma invites his children to a meal. Brahma's children are a metaphor for people who feel they have no control over their imagined reality. They expect to be fed. After the food has been served, he lays down a condition, no one can bend their elbows while getting to the food. The food as a result, cannot be picked up and carried to the mouth. Some children complain, as they cannot feed themselves. Others innovate: they pick up the food, swing their arms and start serving the person next to them. Others feed them in reciprocation.

This is the first exchange, which leads to its codification as a yagna in the Rig Veda. Brahma's children who complain and ignore the value of the exchange came to be known as the asuras; while the children who appreciate its value came to be known as the devas.

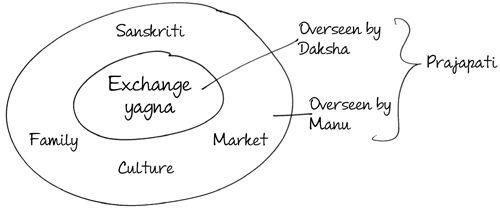

Every interaction in business is a yagna, be it between investor and entrepreneur, employer and employee, manager and executive, professional and vendor, seller and buyer. The yagna is the fundamental unit of business, where everything that can satisfy hunger is exchanged. He who oversees the yagna and makes up its rules is Daksha, or the chief prajapati.

Animals cannot exchange (though some trading and accounting behaviours have been seen in a few species of bats). Exchange is a human innovation that reduces the effort of finding food. It increases the chances of getting fed. It improves the variety of food we get access to. Exchange creates the marketplace, the workplace, even the family. It is the cornerstone of society. He who oversees sanskriti and makes up its rules is called Manu, another prajapati.

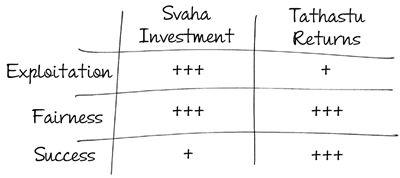

Svaha is food for the devata. Tathastu is food for the yajaman. Unless svaha is given, tathastu cannot be expected. As is svaha, so is tathastu.

Ideally, the yajaman wants the devata to give tathastu voluntarily, joyfully, responsibly and unconditionally. When this happens, it is said Lakshmi walks his way. In the Purans, only Vishnu achieves this. He is identified as bhagavan, he who always feeds others even though he is never hungry.

Madhav has a pan shop near the railway station. He sells betel leaves, betel nuts, sweets and cigarettes. He even has a stash of condoms. He knows that as long as there is a crowd in the station, there will be people with the need to satisfy cravings and pass the time. He offers them pleasures that are legally permitted (though the temptation to offer illegal products is very high). In exchange, they pay money that helps him feed his family. If he did not have a family, he would have, perhaps, stayed back in his village. But he has six mouths to feed, which has brought him to the city where he has had to learn this new trade to earn his livelihood. The day people stop craving betel or nicotine or sweets or sex, his business will grind to a halt. The day his family can fend for itself, he will end this yagna and close down his shop.

Every devata seeks a high return on investment

The yajaman who initiates the yagna is Brahma. So is the devata who participates in the yagna. Both know the value of exchange. Both can also imagine a yagna where both can get tathastu without giving svaha, or get svaha without being obliged to give a tathastu in return. This is a yagna where there is infinite return with no investment. It is the yagna of Brahma's favourite son, Indra, king of devas, performed in Amravati.

Though the two terms sound familiar, deva and devata mean different things. A deva is one of the many sons of Brahma. A devata is the recipient of the yajaman's svaha. A devata may or may not be a deva.

Located beyond the stars, Indra's Amravati houses the wish-fulfilling cow Kamadhenu, wish-fulfilling tree Kalpataru, and the wish-fulfilling jewel Chintamani. Here, the Apsaras are always dancing, the Gandharvas are always singing and the wine, Sura, is always flowing. It's always a party! All hungers are satisfied in Amravati because Lakshmi here is the queen, identified as Sachi. Some would say Sachi is Indra's mistress for while she is obliged to pleasure him, he feels in no way responsible to take care of her.

Amarvati is the land of bhog, of consumption, where all expectations are satisfied without any obligations. For humans, Amravati is swarga, or paradise. Every yajaman yearns for the idle pleasures there. Every son of Brahma—be it deva, asura, yaksha or rakshasa, from Ravan to Duryodhan— wants to be Indra.

It is to attain swarga that a yajaman initiates a yagna and a devata agrees to participate in it. The desire for swarga goads both the yajaman and the devata to be creative and innovative all the time. Both constantly crave more returns, to keep pace with their ever-increasing hunger. Simultaneously, the willingness to put effort in keeps decreasing. Both feel cheated or exploited every time more is asked of them and when growth slows down. Both are happiest when they get a deal or a discount, when they get a bonus or a lottery or a subsidy. The improvement of returns and reduction of investment are the two main aims of every stakeholder in business as humans inch their way towards paradise.

Renjit noticed something peculiar in his town. Young men would gather in the fields in the middle of the day to drink toddy and eat fish. They would not work in the fields. "Work is for the labourers," they said disdainfully. The area has a shortage of workers. People are being called from neighbouring states to work in the fields. The local young men prefer doing deals with high returns like real estate and even gambling. Some are contractors. But when they get contracts from government, they subcontract it to others, so that they can spend the afternoon, like Indra, having a good time.