Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (15 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Conflict is inherent in exchange

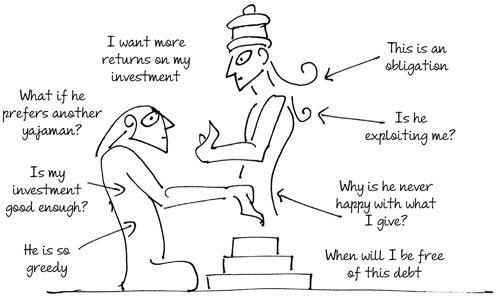

The exercise of exchange is fraught with misunderstandings and problems. The first problem is the burden of expectations and obligations. The yajaman has expectations once he gives svaha, and the devata has obligations once he receives svaha. Exchange creates debt, or rin. With debt come borrowers and lenders. We get entrapped in a maze of give and take, called samsara. We yearn to break free from samsara. We do not want to receive, or give. This is liberation, or mukti. Overseeing the yagna—ensuring that the rules of the yagna are fair to all and respected by all—are the prajapatis, led by Daksha, a son of Brahma.

The second problem is the differing imaginations of both devata and yajaman that often leads to a mismatch between svaha and tathastu. What the devata receives may not be to his satisfaction and what the yajaman receives may not be to his satisfaction. Indra deems his enemies as asuras, or demons, who wish to snatch what he has. The asuras accuse the devas of theft and trickery, of denying them their fair share. This leads to conflict where the devas are constantly at war with the asuras. Sometimes, the devas behave like yakshas, refusing to share what they have, hoarding everything that they possess. Then the asuras transform into rakshasas, who reject every rule of the yagna and simply grab what they want.

The third problem is the anxiety that one day the devata will not want the svaha being offered. He may accept the invitation of another yajaman. Worse, he may seek to outgrow hunger, not expect svaha or give tathastu. Indra especially fears tapasvis—those who engage in tapasya, or introspection. They could turn out to be asuras seeking power to conquer Amravati and take Indra's place. He dispatches his legion of nymphs, the apsaras, to seduce them, and distract them from their goals.

Businesses are always answerable to regulators and tax collectors who accuse them of trying to bypass the system. They have to face the wrath of workers and vendors who feel they are being unfair and exploitative. They are constantly threatened by customers who reject what they have to offer and seek satisfaction elsewhere. There is always a battle to fight: shrinking sales, shrinking margins, labour disputes, attrition, auditors, lawyers, regulators. Plagued by the demands of shareholders, regulators, customers and employees, the yajaman is unable to enjoy Amravati. There is prosperity but no peace. Indra finds his paradise forever under siege.

Gayatri is irritated. She is having problems with her investors who are delaying the next instalment of desperately needed funds. Her uncle, and business partner, is demanding a greater role in the management. Her chief operating officer has quit because he felt there was too much interference from the management. A competitor has poached two of her most prized engineers. The employees are threatening to go on strike if their wages are not increased. And her husband is not giving her the support he'd promised when she started her own business. She feels like Indra with the prajapatis, asuras and tapasvis ganging up against her.

Imagination can help humans outgrow hunger

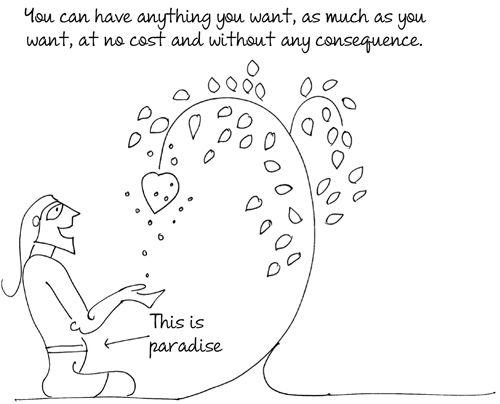

Both the yajaman and the devata seek peace, a place without conflicts. This is only possible in a world where there is no exchange, and no hunger. This is the world of Shiva.

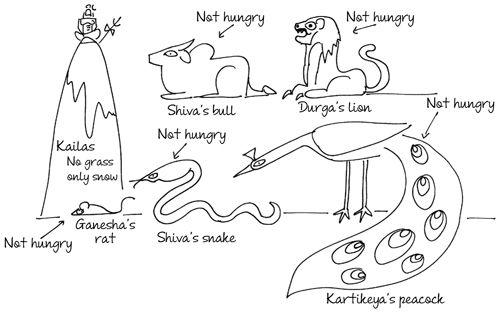

Shiva's abode, Kailas, is a snow-covered mountain where he lives with his wife, Durga, and their children, Ganesh and Kartikeya. There is no grass or any other kind of vegetation on Kailas and yet, Shiva's bull, Nandi, does not seem to mind. Nor does Nandi fear the tigers and lions that serve as Durga's mount. Kartikeya's peacock does not eat Shiva's serpent who, in turn, does not eat Ganesha's rat.

In Kailas there is no anxiety about food; there is no predator or prey. This is because Shiva is the greatest of tapasvis, who has outgrown hunger by performing tapasya, that is, introspection, contemplation and meditation. By churning his imagination, he has found the wisdom that enables him to set Kama aflame with inner mental fire, or tapa. Shiva is ishwar, he who is never hungry. Indra's apsaras have no effect on him. His abode is the land of yoga, not bhog.

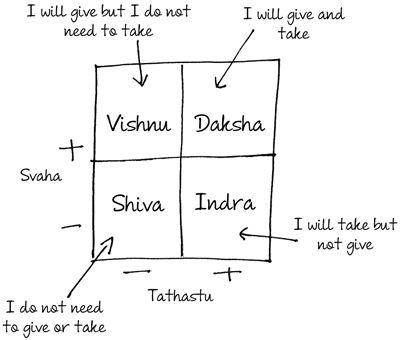

Because Shiva neither seeks tathastu, nor feels the need to give svaha, he invalidates the yagna. Naturally, Daksha dislikes him and deems him the destroyer.

Eshwaran is a rank holder in the university. A scientist, he has the opportunity to work with many international agencies, but he chooses to work in India and teach at a local college. His work is published around the world and he is a recipient of many grants, all of which he has refused, much to the annoyance of his wife. "With grants come obligations," he explains. He values his freedom and his simple life in his ancestral home more than anything else. He nurses no ambition and has no desire to live a lavish lifestyle. His wife argues that he is missing out on many a golden opportunity. "But I do not feel deprived. I am content with what I have. Must supply always generate demand?" His wife has no answer. She never sees her husband complain or fret or fume about the life he has chosen. He feels no envy for those scientists living a more glamorous lifestyle. She feels he could win the Nobel Prize, to which his reply is, "Like it matters to me. I enjoy physics, not the fame that comes with it." Mrs. Eshwaran calls her husband Shiva in her irritation, as his contentment makes her insecure.

Human hunger for the intangible is often overlooked

Every Brahma wants the prosperity of Amravati with the peace of Kailas. This exists only in Vaikuntha, where Lakshmi voluntarily sits at Vishnu's feet. This is ranga-bhoomi, the playground, where everyone feels happy and fulfilled. This is the realm of great affluence and abundance, where milk flows and everyone is showered with gold.

Vishnu is an affectionate god. Like Daksha, he values the role of the yagna in feeding the hungry. He understands that every Indra wants to be fed rather than feed. He knows that true happiness can only come from the wisdom of Shiva, that enables one to outgrow hunger. Vishnu is sensitive to the fact that Brahma and his sons do not see the world as he does. Not that they cannot. They will not. They are afraid.

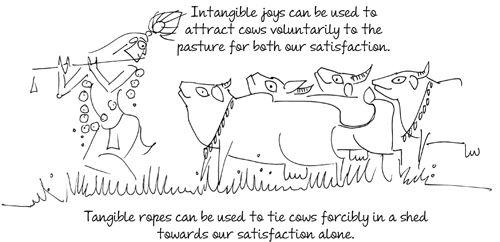

Vishnu focuses on giving svaha. Still he does not feel exploited because he receives intangible returns for tangible investments. His yagna is always successful. He attracts talent, investors and customers like cows to the pasture known as Goloka and helps Brahma and his sons cope with their fears. In exchange, they voluntarily bring with them Lakshmi. Thus does he manage to attract the goddess of wealth his way.

After passing out from a reputed business school, Mahesh, a truly gifted young man, opted not to work in a large multinational and chose to work in a mid-sized Indian ownership firm instead. When asked why by his friends he said, "The multinational firm will hire me for my brilliance and spend years forcing me to fit into a template. Here, I have the freedom to create a template on my own to realize a vision that is my own." Mahesh's new boss, Mr. Naidu, knows that to get the most out of Mahesh, he has to give Mahesh svaha of not just money but also freedom and patience. These are intangible investments that cannot be measured, but they give Mahesh joy and ensure that he works doubly hard. Mr. Naidu does not calculate the returns: a long-term investment demands trust in his assessment of Mahesh.

There are three types of food that can be exchanged during a yagna

Vishnu recognizes that human hunger is not just quantitatively but also qualitatively different. We seek more food. We see different kinds of food. Food is not only tangible; it is also intangible. Power and identity, for instance, are intangible 'foods' that nourish our social and mental bodies.

- We hunger for Lakshmi, or resources, to nourish our physical body (sthula-sharira). So we organize ourselves, create workplaces to extract value from nature, not stopping even when our stomachs are full.

- We hunger for Durga, or power, to make us feel secure. Animals fend for themselves but humans expect to be granted status, dignity and respect through tools, technology, property and rules. Durga nourishes our social body (karana-sharira). In fact, Lakshmi is a surrogate marker for Durga in most cases: we feel safer when we have money.

- We hunger for Saraswati, or identity, to nourish our mental body (sukshma-sharira). This is an exclusively human need that makes us curious about nature as well as imagination. We study it, understand it, control it, determined to locate ourselves in this limitless impermanent world that seems to relentlessly invalidate us. In fact, Lakshmi and Durga are compensations when the hunger for Saraswati is not satisfied.

While Indra sees the yagna only as an exchange of Lakshmi, Vishnu sees the yagna as an exchange of Lakshmi, Durga and Saraswati. These three goddesses are for him three forms of Narayani, the goddess of resources. Narayani is prakriti seen through human eyes. The more we see, the more she reveals herself.

Drishti reveals Lakshmi; divya-drishti reveals Durga; darshan reveals Saraswati. This is the Narayani potential. As long as the gaze is limited and the mind contracted, Brahma will either behave like Daksha, focusing on the yagna more than the yajaman, or he will give birth to a son who aspires to be Indra, focused on his self-actualization, indifferent to the needs of others. But when the gaze widens and the mind expands, when varna rises and the sattvaguna blooms, he makes his journey towards the independent Shiva and the dependable Vishnu.