Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (34 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Things are surrogate markers of our value

Indra calls Vishwakarma, his architect, and orders him to build a palace worthy of his stature. Vishwakarma builds a palace of gold but Indra feels it is not good enough. So Vishwakarma builds him a palace of diamonds; Indra is not satisfied with that either. So Vishwkarma builds him a palace using that most elusive of elements, ether; even this does not please Indra.

Why does Indra want to build a larger palace? Is not being king of the devas enough? Clearly not; he needs his mental status to have a tangible manifestation in the form of a palace. But no palace matches his mental expectation, as his mental body is much greater than all the things he can possess. That leaves him dissatisfied.

In the world Indra lives in, people are measured by the amount of things they have. Since he wants to be bigger and better than everyone else, he wants his palace to be bigger and better than others'.

Property is a physical manifestation of our mental body. It contributes to our social body. What we have determines who we are. We cannot see the mental body, but we do see the social body. Our possessions become an extension of who we are. We equate ourselves with what we have. When we die, what we have outlives us, thus possessions have the power to grant us immortality. That is why property is so dear to humans.

Raju hated driving. Since he could not afford a driver, he did not buy a car. He travelled every day to office by auto. This annoyed his boss. "Your team members will not respect you unless you have a car." Raju did not understand this: surely they respected him for his work and managerial skills. Nevertheless, he finally succumbed to the pressure and bought a car. His son was very annoyed, "But daddy, all my friends have bigger cars." Raju realized the car was not only a mode of conveyance; it was about grabbing a place in the social hierarchy.

Thoughts can be coded into things

Narad asked the wives of Krishna to give him something that they felt was equal in value to their husband. He gets a weighing scale into the courtyard and makes Krishna sit on one of the pans. On the other, each of the wives put what they feel equals Krishna's worth. Satyabhama puts all her gold, utensils and jewels, but the scale still weighs less than Krishna. Rukmini, on the other hand, places a sprig of tulsi on the pan and declares it to be a symbol of her love for Krishna. Instantly, the scales shift.

Both Satyabhama and Rukmini value Krishna for the impact he has had on them. How does one quantify this transformation? How do they give form to their mental image of him? Satyabhama expresses her thoughts through things while Rukmini uses a symbol, a metaphor. When people recognize this code, the tulsi becomes more valuable than gold. Everyone values gold. Only those who appreciate the language of symbols will appreciate tulsi.

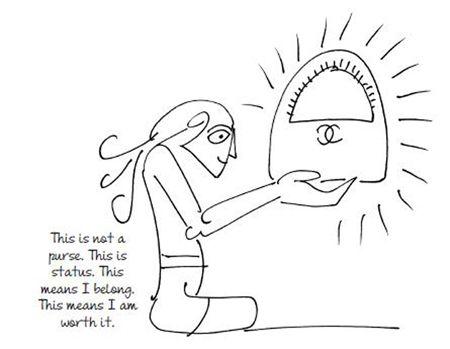

The same principle applies to brands. Brands are thoughts embodied by things. When people buy a brand, they are buying a thought or a philosophy that makes them feel powerful, which raises their stature in the eyes of those who matter to them. Naturally, people are willing to pay a lot of money for such codes. The cost of making a product is much less than the cost at which brands are sold. In order to charge a premium, great effort has to be made through advertising and marketing to establish the brand's philosophy in a cultural landscape. Unless people are able to decode what the brand stands for, it will have no value.

Zafar has a small shop that sells fake brands at about a quarter of the real price. He has never understood why people pay so much for brand names. The actual cost of production is much lower. His uncle explained, "The customer is not buying a tool that tells the time. He is buying aukaat: status, dignity, respect, admiration and envy. For that the customer is ready to pay anything." Zafar thus understood the difference between the literal and symbolic value of Rukmini's tulsi.

We assume we are what we have

Paundraka, king of Karusha, wears a crown with a peacock feather. He holds a lotus flower in one hand and a conch-shell in the other. Around his neck he wears a garland of forest flowers, the Vanamali. From his ears hang earrings that are shaped like dolphins, the Makara-kundala. He is draped in a bright yellow silk dhoti or the Pitambara. He even has hairdressers curl his hair. He insists on eating rich creamy butter with every meal. He plays the flute in flowery meadows on moonlit nights surrounded by his queens and concubines who dance around him. "I look like Krishna. I do everything Krishna does. I must be Krishna," he says to himself. His subjects, some gullible, some confused and others frightened, worship him with flowers, incense, sweets and lamps. Everyone wonders who the true Krishna is since both look so similar?

Then a few courtiers point out that Krishna of Dwaraka has a wheel-shaped weapon that no other man has called the Sudarshan Chakra. "Oh that," Paundraka explains, "He borrowed it from me. I must get it back from the impostor." So a messenger is sent to inform Krishna to return the Sudarshan Chakra or face stern consequences. To this, Krishna replies, "Sure, let him come and get it."

Irritated that Krishna does not come to return the Sudarshan Chakra, Paundraka sets out for Dwaraka on his chariot, decorated with a banner that has the image of Garud on it, reinforcing his identity. When he reaches the gates of Dwaraka, he shouts, "False Krishna, return the Sudarshan Chakra to the true Krishna." Krishna says, "Here it is." The Sudarshan Chakra that whirrs around Krishna's index finger flies towards Paundraka. Paundraka stretches out his hand to receive it. As the wheel alights on his finger, he realizes it is heavier than it looks. So heavy, in fact, that before he can call for help he is crushed to pulp under the great whirring wheel. That is the end of the man who pretended to be Krishna.

The corporate world is teeming with pretenders and mimics. They think they know how to walk the walk and talk the talk but they simply don't know what the talk is all about. They know how to dress, how to carry their laptops and smart phones, what car to drive, where to be seen, with whom, how to use words like 'value enhancement' and 'on the same page' and 'synergy' and 'win-win'. In other words, they know the behaviour that projects them as corporate leaders, but are nowhere close to knowing what true leadership actually means.

At a fast-growing firm, Vijaychandra selects a young man who shows all the signs of having the talent and drive of a leader. The young man's name is Jaipal. His CV indicates he's from the right universities, has the right credentials and impressive testimonies. Besides which, he's also nattily dressed and articulate. He even plays golf! He is fit to head the new e-business division. Two years down the line, however, despite all the magnificent PowerPoint presentations and Excel sheets, which impressed quite a few investors, the e-division's revenue is way below the mark. The market has just not responded. Jaipal knows how to talk business, but evidently he does not know how to do business. Vijaychandra decides to investigate what Jaipal has done in the past two years. It emerges that while Jaipal has stayed in the right hotels and driven the right cars, he has never gone to personally meet the vendors or customers. He has not made the effort to immerse himself in market research; on the contrary, he has hired people to do it for him. He focuses on 'strategy' but not on 'tactics'. He loves boardroom brainstorming but not shop-floor sweat. His organization structure is designed such that it keeps him isolated from the frontline. He simply assumes that his team will know what to do in the marketplace. He has never picked up the phone and addressed client grievances—he prefers the summary of conclusions provided by reputed analysts. He does not get to hear his sales people whine and groan and prefers the echoes of the market presented by strategy consultants. Vijaychandra realizes he has a Paundraka on his hands—all imitation, no inspiration.

We expect things to transform us

One day, as King Bhoj and his soldiers approach a field, a farmer is heard screaming, "Stay away, stay away, you and your horses will destroy the crops. Have some pity on us poor people!" Bhoj immediately moves away. As soon as he turns his back, the farmer begins to sing a different tune altogether and says, "Where are you going, my king? Please come to my field, let me water your horses and feed your soldiers. Surely you will not refuse the hospitality of a humble farmer?" Not wanting to hurt the farmer, though amused by his turnaround, Bhoj once again moves towards the field. Again, the farmer shouts, "Hey, go away. Your horses and your soldiers are damaging what is left of my crop. You wicked king, go away." No sooner has Bhoj begun to turn away than the farmer cries, "Hey, why are you turning away? Come back. You are my guests. Let me have the honour of serving you."

The king is now exceedingly confused and wonders what is conspiring. This happens a few more times before Bhoj observes the farmer carefully. He notices that whenever the farmer is rude, he is standing on the ground, but whenever he is hospitable, he is standing atop a mound in the middle of the field. Bhoj realizes that the farmer's split personality has something to do with the mound. He immediately orders his soldiers to dig up the mound in the centre of the field. The farmer protests but Bhoj is determined to solve the mystery.

Beneath the mound, the soldiers find a wonderful golden throne. As Bhoj is about to sit on it, the throne speaks up, "This is the throne of Vikramaditya, the great. Sit on it only if you are as generous and wise as he. If not, you will meet your death on the throne." The throne then proceeds to tell Bhoj thirty-two stories of Vikramaditya, each extolling a virtue of kingship, the most important being generosity. It is through these stories that Bhoj learns what it takes to be a good king.

The story is peculiar. In the first part of the story, the throne transforms the stingy farmer into a generous host. In the latter half, the throne demands the king be generous before he takes a seat.

In organizations, we expect a man in a particular position to behave in a particular manner. We assume that he has gained this position because he has those qualities. But what comes first: gaining the qualities or acquiring the position. Can a king be royal before he has a kingdom, or does the possession of a kingdom make him royal?

Can a person who seeks Durga from the outside world give out Durga? Or should a king have enough Shakti within him to be an unending supply of Durga to others?

Sunder was great friends with his team before he became the boss. The moment he was promoted, he started behaving differently, became arrogant, obnoxious and extremely demanding. Was it the role that had changed him or had it allowed him to reveal his true colours? Sunder blames the burden of new responsibilities and the over-familiarity of his colleagues as the cause of friction. That is when, Kalyansingh, the owner of the company, decides to have a chat with him. "Do you know why you have been given a higher salary, a car, a secretary, a cabin?" Sunder retorts that these are the perks of his job. Kalyansingh then asks, "And what is your job?" Sunder rattles off his job description and his key result areas. "And how do you plan to get promoted to the next level?" Sunder replies that it will happen if he does his work diligently and reaches his targets. "No," says Kalyansingh, "Absolutely not." Sunder does not understand. Kalyansingh explains, "If you do your job well, why would I move you? I will keep you exactly where you are." Looking at the bewildered expression on Sunder's face, Kalyansingh continues, "If you nurture someone to take your place, then yes, I may consider promoting you, but you seem to be nurturing no one. You are too busy trying to be boss, trying to dominate people, being rude and obnoxious. That is because you are insecure. So long as you are insecure, you will not let others grow. And as long as those under you do not grow, you will not grow yourself. Or at least, I will not give you another responsibility. You will end up doing the same job forever. Is that what you really want?" That is the moment Sunder understands the meaning of Vikramaditya's throne. After all, it is not about behaving royally, but rather about nurturing one's kingdom. He must not take Durga, he has to give Durga.