Chernobyl Strawberries (13 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

The Goldsworthy campaign trail

For at least a couple of years after âwe' won that election, I remained an ardent royalist and a true-blue Conservative, in what was neither the first nor the last of my spectacular political U-turns (by then, though, I was sufficiently aware of my own fickleness not to be inclined to formalize membership of any organization). It was disappointing to learn that one didn't necessarily become any wiser as one grew older, although the âwait and see' policy â as advocated by my father â finally began to show distinct advantages. If you stood âwaiting and seeing' long enough, you were bound to catch me on my next revolution.

The only time I had to account for the communism business was before a bespectacled young man in the consular section of the US embassy in Grosvenor Square. In the eighties, before I acquired British citizenship, I had some entertaining times there applying for a US entry visa on my old Red passport. Obviously, I had to tick the Yes box against the âAre you or were you ever a member of a Communist, Terrorist or similar organization?' question on the visa application. I needed to provide explanatory details on the dotted line and the best I could come up with was âThe Yugoslav Communist Party was never really a communist party and I never paid my membership fees.' Feeble, perhaps, but it seemed to impress the young man. In sheer bravado, I decided to tell him about my ongoing electioneering activities. The initial explanation was more than sufficient to get me into the United States, but I was not one to do anything by half. Before my very eyes, I was finally turning into one of those dissidents from Hollywood movies. I was the kind of woman who gamely sleeps with the hero on his brief assignment behind the Iron Curtain and is then sentenced to life imprisonment or casually shot at a checkpoint. The bespectacled young man played with the cuffs of his Brooks Brothers shirt. I loved his accent. I loved his college ring. I wanted to become his friend. Like Maggie, I was, at that stage, in love with everything American. I was eager to hit the road with my thirty-day Greyhound pass, counting on doing a state a day at least, with a copy of

On the Road

in my rucksack. A rejection would have been devastating.

My earliest oath of allegiance, way back in 1968, is the only one I still remember word for word, even after all these years. âToday, as I become a pioneer, I promise that I will study and work industriously, respect my parents and my elders and be a

sincere, trusted friend who keeps a given word,' I echoed in a choir of thin, seven-year-old voices, sixty or so kids from the first grade of the 22 December Primary School. We were gathered on the glorious stage of the central hall in the guards' barracks in the Belgrade suburb of Topchider, in front of dozens and dozens of men in uniform, teachers, parents and older pupils, all dressed up to the nines to celebrate our school day. It was also Army Day hence the top brass: such attempts at across-the-line socializing were clearly good for army PR. The room was dripping with gold braid.

The new pioneers were dressed in identical white shirts, navy trousers and pleated skirts, white stockings, black lace-ups or patent-leather shoes, and brand-new triangular red scarves around the neck, with the emblem of the Pioneers' Union. The officers stood up and saluted with an outstretched hand, fingers aligned at an angle of forty-five degrees just above the right temple; the pioneers responded with a clenched fist, the longest way up, the shortest down. Fatherly figures looked down at all of us from the photographs suspended in large frames above the stage. In one of them Comrade Tito and his wife, Comrade Jovanka, were sharing a laugh with a group of young pioneers just like us. He was dressed in a white naval uniform, she in a demure little black dress with a posy of flowers in her hands, the beehive hairdo fashionable in the fifties towering over his officer's hat by a couple of inches.

Layers of fine snow, thick and softer than goose-down, covered the valley of Topchider, bedecking its former royal hunting lodge and sprinkling the hills around it. Snowflakes went on falling silently beyond the tall French windows, and their glorious light filtered through the white silk curtains. I stood out in front of the group and started reciting a long ballad about the glory and pain of the Fourth Partisan Offensive in 1943, when the heroic troops (âour fighters') marched

for days from north-west Bosnia, across the Neretva river to the safety of Montenegro, with 4,000 wounded and thousands of refugees in tow. (A film version of the battle, with Yul Brynner, Orson Welles and Franco Nero, was one of those spectacles we later saw whenever no one could think of a better thing to do on a school away-day.)

My voice trembled as the presenter lowered the microphone by a foot or two, then steadied itself. I fluffed not once. My mother, resplendent in a sky-blue Chanel suit, with a little white fur collar and pearl earrings, her eyes filled with tears, led the applause from the fifth row. She was thirty-four, small and elegant, her eyes the colour of cornflowers, her hair the colour of mahogany, a glorious crown of thick curls. She was the most beautiful woman in that vast room. I was clearly the chosen one.

My sister and I spent the following day sledging on a hillock which was known to the local kids as Hiroshima. Halfway down, it had a bump which made the sledges jump and land about a foot further on, with the thuds of wood followed by thuds of little bottoms and excited screams. My sister, aged five, was a picky eater, weighing barely two and a half stone, with the long face of Anne Frank. She was endlessly pursued by my mother and my grandmother with spoonfuls of cod liver oil and tasty morsels of this or that. She subsisted mainly on crusty bread with homemade damson jam. We were known to take jars of jam on holiday with us for fear that she would not want to eat any hotel food, in spite of the protestations of my father, who argued that children never starved themselves to death if food was on offer, whatever it may be. On Hiroshima, my skinny sister flew higher and screamed louder than any of us.

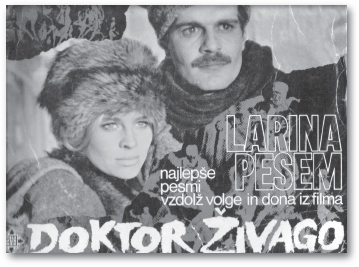

My first LP

I was just pulling her on a sledge back towards the house, our fingers and toes frozen solid and our lips and noses blue, when my father turned the corner, tall and imposing in his black Crombie coat, with a paisley scarf, black beret and black leather gloves. He looked like a fifties matinée idol, a cross between Cary Grant and Clark Gable, with a thicker moustache and larger, more sensitive eyes than either of those two. His face was beaming and he was carrying a small black valise with metal trimmings which looked like an old-fashioned explosive device. Once inside the house, he opened the valise to reveal a set of speakers and a turntable with a button which could be pointed towards 16, 33 and 45. It was the Beat Boy, our first ever, East German-made, gramophone. From under his long coat my father produced a vinyl record in a dark green sleeve. The faces of Julie Christie and Omar Sharif were staring at us from the cover, his puppy eyes dark brown, hers improbably

green. In the corner of the room, below a tall Christmas tree which stood, still undecorated, on its wooden cross, I was being led into the foothills of my love affair with Strelnikov.

My father slowly took his coat off, carefully put the record on and asked Mother to dance. My sister went to fetch herself a

tartine

of bread and jam. The two of them, he large and tall and dark, she fair, tiny and childlike in her size-three flat fur slippers, just stood there looking at each other, and then at me looking at them.

I last saw Strelnikov in early 1987, on the frozen platform of Budapest's Keleti Station, walking the twenty or so yards alongside my carriage, up and down and back again, little heaps of dirty snow crunching under his highly polished boots. His grey officer's overcoat and grey fur hat with a shiny enamel red star on it made him appear even taller than he already was. With his cropped blond hair and blue eyes he looked like a lost deity from some Slavonic

Götterdämmerung

.

My Belgrade-bound train was coming from Moscow and he had obviously been sent to meet someone who had failed to materialize. The station was dark and full of smoke and my carriage smelled of wurst and coal. People with yellowish skin, badly cut clothing and strange footwear, once so typical of winters in the Eastern Bloc, gave him a wide berth as they passed, their expressions filled with barely disguised hatred. He could not have been much older than twenty-five, a Russian boy who stood alone in an empty circle on a crowded platform, not looking at anyone, until, at one moment, he lifted his head towards the carriage and his eyes met with mine. I smiled. He gave me a long absent-minded glance, but his face remained inscrutable and distant. He never smiled back.

BETWEEN THE AGES

of four and twenty-four I wrote poetry every day. It is debatable how far one could divide the days into good and bad as regards the production line, but on some I wrote as many as four hundred lines of verse â running up to ten separate poems â while on others I polished a single couplet until it had not a single word in common with the original version, and then back again.