Chernobyl Strawberries (15 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

One of the nicest things about being a poet in socialist Yugoslavia was the idea that poetry mattered. State subsidy enabled poetry magazines to flourish and each two-horse town had a poetry festival all of its own. You could take part in those without having to pay five pounds for the first submission and two-fifty for each subsequent one, as you do in Britain, and I frequently did. By the time I was twenty-three, I had built a reputation as a moderately known poet, with a string of publications, one or two poetry prizes and regular high-profile readings on television poetry programmes. (I am not sure if even BBC4 would dare to schedule these in Britain.) I also developed admirable skills for rejecting excited poetic suitors with stories of boyfriends of long standing, although in a short while I began to feel distinctly bored after any stretch of time in the more mundane world of civvy street, where men generally tried to control their passions. I was aiming to publish a collection of my poems, which was more difficult, but not entirely beyond reach. Thank God I never succeeded in that particular effort.

There was an annual competition for the publication of a first book by a young poet which normally attracted quite a lot of media attention. It had to, for journalists were under orders to cultivate young poets at the juncture where they could still be encouraged to turn into fully blown suits. My manuscript was short-listed and then rejected and I went to see the poetry editor, whose sad duty it was to have to explain rejection to all

of us near-misses without discouraging us en masse. The poetry editor himself was a well-known provincial, neo-surrealist poet, and the main organizer of a number of quite outrageous âhappenings' around town, with a ridiculous name (as though his parents sensed the neo-surrealist angle even at birth). âIt's a fine collection, Vesna, mature well beyond your young years,' he said, welcoming me into a tiny, smoke-filled office on the first floor of an apartment block in a side street just off the main drag.

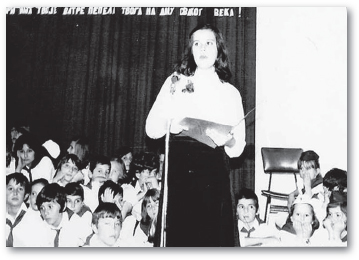

The young poet

My poetry could hardly have failed to register as âmature well beyond my young years' when it was full to bursting with the most recherché inter-textual allusions while at the same time brimming with references to the wilder kind of carnal experience, which was, I hardly need to say, derived largely from book reading (that early encounter with DHL

had

to leave an imprint somewhere, I guess). âFine collection, indeed, but

lacking any sense of irony. You take yourself too seriously, my dear,' he continued, hitting the nail on the head. (All my poetic idols, from Alfred, Lord Tennyson, to Milan Rakic, took themselves very seriously indeed: grand, erudite and full of self-love was what I aimed to be.) âHow about a drink now, my dear child?' the editor punch-lined. I had to meet my âboyfriend' immediately.

The themes of my poetry could be broadly divided into two subcategories: one, melancholy, self-indulgent love poetry; the other, Brechtian, rebellious, satirical and political. (The latter was likely to get me into trouble eventually, if I didn't watch it.) My earliest successful poems â successful in the sense of getting into print â were social-observational. However, I continued to write love poetry even when I was most certainly not in love with anyone. One of the earliest poems, entitled âI Cried Like a Red Poppy in a Field of Wheat' and written when I was barely six, reveals all the characteristics of the genre which I was to polish and perfect through many years of wrestling with my melancholy, self-indulgent teenage muse.

I was particularly fond of penning what I now call a Penelope poem. In it, the female poetic subject is longing for an absent male, who is â normally because of

some force majeure â

obliged to go on travelling for years, leaving the said (sad) subject condemned to waiting, which she does, doggedly and faithfully, knitting, weaving, picking flowers, whatever. While the male subject is most often a known lover, he is sometimes as yet unmet (Penelope promises to recognize him when he finally decides to turn up). He is often just an ordinary male person with some special qualities, but he can equally have pseudo-religious powers: Jesus-like, omnipresent and all-knowing, and good beyond comprehension.

In many of these poems, the female who waits (the waitress) assumed a sexual authority, experience and world-weariness which the author arguably did not possess. Imagine sonnets written by Lady Caroline Lamb and you wouldn't be far off: while Byron is off in Missolonghi, what's the girl to do but write poetry? Throughout my late teens I used to show manuscripts to boyfriends, who tended to be unbothered by the fact that the poems were obviously not about them, and sometimes got rather too excited by the promise of adventure the verse contained.

By the time I hit my early twenties, I decided, in Marxist parlance, to wed theory and practice more closely, and began to affect the appearance of an incipient bohemian. I smoked filterless little cigarettes, allegedly favoured by Joseph Vissarionovich, which went very well with tiny glasses of grappa as strong as absinthe, a black duffel coat, a short crop (I was almost as breathless as Jean Seberg) and

an affaire du coeur

with Andrei, a white-haired literary scholar some thirty years older than me, who was not very interested in my poetry but immensely concerned to ensure that I didn't keep a diary.

He was so fond of lecturing that he couldn't really stop himself, and I loved that. Over the three years which followed, I learned more from him than from the entire university department at which I was studying. In the midst of it all, I suddenly stopped writing poetry, which pleased him no end, for, although he lived for the poetry of the past, he always seemed to find living poets slightly embarrassing, perhaps because he believed that the noblest emotions are the ones we repress. Soon afterwards I started two-timing him with a boy of my age and left, but continued to check out his books as they appeared, every year just before the book fair, hoping that one would be dedicated to me. The urge to be inspirational was, for a long while, much greater than the urge to be inspired, which

is, perhaps, a woman thing. The strangest aspect of it all is that, in spite of spending literally hours and hours together, and most of them quite alone, we kissed only once. The man remains an enigma.

My greatest measurable achievement as a poet turned out to be taking part in the celebration of Comrade Tito's ninety-second birthday, or what would have been his ninety-second birthday had he not chosen to die just before his eighty-eighth. (During the lull before the storm of steel which shook my homeland in the nineties, âofficial' Yugoslavia practised a strange form of necrophilia towards its erstwhile president for life.) In my household, the preparations had been debated for days. The discussion did not focus so much on the advisability of taking part, or the choice of poem â

that

would have been too rational; rather, we argued incessantly about what exactly I was going to wear. One had to think about the fact that the event was taking place before a live audience of 30,000 which gathered annually at a football stadium for the big day, people for whom I would represent no more than a distant blob of colour, and a further couple of million or so half-hearted TV viewers who were still watching the show out of a habit acquired in the long afternoon of Yugoslav socialism. For them, my poem would be â like the Archbishop of Canterbury's sermon at Lady Diana's wedding to Prince Charles â most probably a suitable window for a âtea or pee' break. (No advertising was allowed to spoil the event.)

The exact outfit was the subject of heated arguments between myself, my mother, an assortment of relations and anyone else who cared to contribute. There was never a shortage of opinion, free of charge, in my neighbourhood. I was not really sure. One day I was certain it would be a pair of jeans with a white T-shirt and a pair of Converse All-Star trainers. (Blue or red

starke

, as they were called in Serbo-Croat, were the uniform footwear of my

lycée

clan.) My mother prepared to commit suicide. Next day I dreamed of a little black dress and Audrey Hepburn hair. Mother and the director of the show protested that black was highly inappropriate and suggested red. âYour colour,' said my mother. â

Our

colour,' said the director. âPeasant,' mumbled my sister. She used the feminine form of the noun. There was no doubt that she had me in mind. Only peasants wrote poetry anyway. (The word

peasant

, with its full power of character assassination, is not really translatable into English. It was neither here nor there as far as the real peasantry were concerned, but a poisoned dart if directed at a Belgrade student of letters.) Red, black or white, it made no difference. Writing poetry was not cool. Not unless sung, accompanied by no more than a single instrument, and even then only in alternative clubs with audiences in double digits. I couldn't count on my sibling's advice.

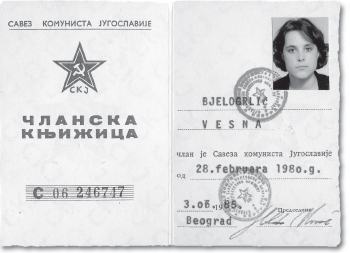

My Communist Party membership card