Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 (17 page)

Read Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453 Online

Authors: Roger Crowley

The Ottomans were probably already casting guns at Edirne by this time; what Orban brought was the skill to construct the moulds and control the critical variables on a far greater scale. During the winter of 1452, he set to on the task of casting what was probably the largest cannon ever built. This painstaking and extraordinary process was described in detail by the Greek chronicler, Kritovoulos. Initially, a barrel-shaped mould some twenty-seven feet long was constructed of clay mixed with finely chopped linen and hemp. The mould was of two widths: the front compartment for the stone ball had a diameter of thirty inches, with a smaller after-chamber to take the powder. An enormous casting pit had to be excavated and the fired clay core was placed in it with the muzzle face down. An outer cylindrical clay casing ‘like a scabbard’ was fashioned to fit over this and held in position, leaving space between the two clay moulds to receive the molten metal. The whole thing was packed about tightly with ‘iron and timbers, earth and stones, built up from outside’ to support the huge weight of the bronze. At the last moment wet sand would be drizzled around the mould and the whole thing covered over again, leaving just a hole through which the molten metal could be poured. Meanwhile Orban constructed two brick-lined furnaces faced with fired clay inside and out and reinforced with large stones – sufficient to withstand

a temperature of 1,000 degrees centigrade – and surrounded on the outside by a mountain of charcoal ‘so deep that it hid the furnaces, apart from their mouths’.

The operation of a medieval foundry was fraught with danger. A visit by the later Ottoman traveller, Evliya Chelebi, to a gun factory catches the note of fear and risk surrounding the process:

On the day when cannon are to be cast, the masters, foremen and founders, together with the Grand Master of the Artillery, the Chief Overseer, Imam, Muezzin and timekeeper, all assemble and to the cries of ‘Allah! Allah!’, the wood is thrown into the furnaces. After these have been heated for twenty-four hours, the founders and stokers strip naked, wearing nothing but their slippers, an odd kind of cap which leaves nothing but their eyes visible, and thick sleeves to protect the arms; for, after the fire has been alight in the furnaces twenty-four hours, no person can approach on account of the heat, save he be attired in the above manner. Whoever wishes to see a good picture of the fires of Hell should witness this sight.

When the furnace was judged to have reached the correct temperature the foundry workers started to throw copper into the crucible along with scrap bronze probably salvaged, by a bitter irony for Christians, from church bells. The work was incredibly dangerous – the difficulty of hurling the metal piece by piece into the bubbling cauldron and of skimming dross off the surface with metal ladles, the noxious fumes given off by the tin alloys, the risk that if the scrap metal were wet, the water would vaporize, rupturing the furnace and wiping out all close by – these hazards hedged the operation about with superstitious dread. According to Evliya, when the time came to throw in the tin:

the Vezirs, the Mufti and Sheikhs are summoned; only forty persons, besides the personnel of the foundry, are admitted all told. The rest of the attendants are shut out, because the metal, when in fusion, will not suffer to be looked at by evil eyes. The masters then desire the Vezirs and sheikhs who are seated on sofas at a great distance to repeat unceasingly the words ‘There is no power and strength save in Allah!’ Thereupon the master-workmen with wooden shovels throw several hundredweight of tin into the sea of molten brass, and the head-founder says to the Grand Vizier, Vezirs and Sheikhs: ‘Throw some gold and silver coins into the brazen sea as alms, in the name of the True Faith!’ Poles as long as the yard of ships are used for mixing the gold and silver with the metal and are replaced as fast as consumed.

For three days and nights the lit charcoal was superheated by the action of bellows continuously operated by teams of foundry workers until the keen eye of the master founder judged the metal to be the right tone of molten red. It was another critical moment, the culmination

of weeks of work, involving fine judgement: ‘The time limit having expired … the head-founder and master-workmen, attired in their clumsy felt dresses, open the mouth of the furnace with iron hooks exclaiming “Allah! Allah!” The metal, as it begins to flow, casts a glare on the men’s faces at a hundred paces’ distance.’ The molten metal flowed down the clay channel like a slow river of red-hot lava and into the mouth of the gun mould. Sweating workers prodded the viscous mass with immensely long wooden poles to tease out air bubbles that might otherwise rupture the gunmetal under fire. ‘The bronze flowed out through the channel into the mould until it was completely full and the mould totally covered, and it overflowed it by a cubit above. And in this way the cannon was finished.’ The wet sand packed round the mould would hopefully slow the rate of cooling and prevent the bronze cracking in the process. Once the metal was cold, the barrel was laboriously excavated from the ground like an immense grub in its cocoon of clay and hauled out by teams of oxen. It was a powerful alchemy.

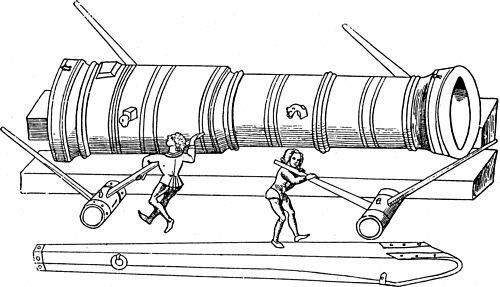

Fifteenth-century cast cannon

What finally emerged from Orban’s foundry after the moulds had been knocked out and the metal scraped and polished was ‘a horrifying and extraordinary monster’. The primitive tube shone dully in the winter light. It was twenty-seven feet long. The barrel itself, walled with eight inches of solid bronze to take the force of the blast, had a

diameter of thirty inches, big enough for a man to enter on his hands and knees and designed to accommodate a monstrous stone shot eight feet in circumference weighing something over half a ton. In January 1453 Mehmet ordered a test firing of the great gun outside his new royal palace at Edirne. The mighty bombard was hauled into position near the gate and the city was warned that the following day ‘the explosion and roar would be like thunder, lest anyone should be struck dumb by the unexpected shock or pregnant women might miscarry’. In the morning the cannon was primed with powder. A team of workmen lugged a giant stone ball into the mouth of the barrel and rolled it back down to sit snugly in front of the gunpowder chamber. A lighted taper was put to the touch hole. With a shattering roar and a cloud of smoke that hazed the sky, the mighty bullet was propelled across the open countryside for a mile before burying itself six feet down in the soft earth. The explosion could be heard ten miles off: ‘so powerful is this gunpowder’, recorded Doukas, who probably witnessed this test firing personally. Mehmet himself ensured that ominous reports of the gun filtered back to Constantinople: it was to be a psychological weapon as well as a practical one. Back in Edirne Orban’s foundry continued to turn out more guns of different sizes; none were quite as large as the first supergun, but a number measured more than fourteen feet.

During early February, consideration turned to the great practical difficulties of transporting Orban’s gun the 140 miles from Edirne to Constantinople. A large detachment of men and animals was detailed for the task. Laboriously the immense tube was loaded onto a number of wagons chained together and yoked to a team of sixty oxen. Two hundred men were deployed to support the barrel as it creaked and lurched over the rolling Thracian countryside while another team of carpenters and labourers worked ahead, levelling the track and building wooden bridges over rivers and gullies. The great gun rumbled towards the city walls at a speed of two and a half miles a day.

6 The Wall and the Gun

1

‘From the flaming …’, quoted Hogg, p. 16

2

‘an expert in …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 40

3

‘dredged the fosse …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli,

p. 37

4

‘a seven-year-old boy …’, Gunther of Pairis, p. 99

5

‘one of the wisest …’, quoted Tsangadas, p. 9

6

‘the scourge of God’, quoted Van Millingen,

Byzantine Constantinople

, p. 49

7

‘in less than two months …’, quoted ibid., p. 47

8

‘This God-protected gate …’, quoted ibid., p. 107

9

‘a good and high wall’, quoted Mijatovich, p. 50

10

‘struck terror …’, quoted Hogg, p. 16

11

‘made such a noise …’, quoted Cipolla, p. 36

12

‘the devilish instrument of war’, quoted DeVries, p. 125

13

‘If you want …’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

pp. 247–8

14

‘like a scabbard’, Kritovoulos

,

Critobuli, p. 44

15

‘iron and timbers …’, ibid., p. 44

16

‘so deep that …’, ibid., p. 44

17

‘On the day …’, Chelebi,

In the Days

, p. 90

18

‘the Vezirs …’, ibid., p. 90

19

‘The time limit having expired …’, ibid., p. 91

20

‘The bronze flowed out …’, Kritovoulos,

Critobuli

, p. 44

21

‘a horrifying and extraordinary monster’, Doukas,

Fragmenta,

p. 248

22

‘the explosion and …’, ibid., p. 249

23

‘so powerful is …’, ibid., p. 249

MARCH

–APRIL

1453

When it marched, the air seemed like a forest because of its lances and when it

stopped, the earth could not be seen for tents.

Mehmet’s chronicler, Tursun Bey, on the Ottoman army

Mehmet needed both artillery and numerical superiority to fulfil his plans. By bringing sudden and overwhelming force to bear on Constantinople, he intended to deliver a knockout blow before Christendom had time to respond. The Ottomans always knew that speed was the key to storming fortresses. It was a principle clearly understood by foreign observers such as Michael the Janissary, a prisoner of war who fought for the Ottomans at this time: ‘The Turkish Emperor storms and captures cities and also fortresses at great expense in order not to remain there long with the army.’ Success depended on the ability to mobilize men and equipment quickly and on an impressive scale.

Accordingly, Mehmet issued the traditional call to arms at the start of the year. By ancient tribal ritual, the sultan set up his horsetail banner in the palace courtyard to announce the campaign. This triggered the dispatch of ‘heralds to all the provinces, ordering everyone to come for the campaign against the City’. The command structure of the two Ottoman armies – the European and the Anatolian – ensured a prompt response. An elaborate set of contractual obligations and levies enlisted men from across the empire. The provincial cavalry, the

sipahis

, who provided the bulk of the troops, were bound by their ties as landholders

from the sultan to come, each man with his own helmet, chain mail and horse armour, together with the number of retainers relative to the size of his holding. Alongside these, a seasonal Muslim infantry force, the

azaps

, were levied ‘from among craftsmen and peasants’ and paid for by the citizens on a pro-rata basis. These troops were the cannon fodder of the campaign: ‘When it comes to an engagement,’ one cynical Italian commented, ‘they are sent ahead like pigs, without any mercy, and they die in great numbers.’ Mehmet also requisitioned Christian auxiliaries from the Balkans, largely Slavs and Vlachs, obligated under the laws of vassalage, and he prepared his elite professional household regiments: the infantry – the famous Janissaries – the cavalry regiments and all the other attendant corps of gunners, armourers, bodyguards and military police. These crack troops, paid regularly every three months and armed at the sultan’s expense, were all Christians largely from the Balkans, taken as children and converted to Islam. They owed their total loyalty to the sultan. Although few in number – probably no more than 5,000 infantry – they comprised the durable core of the Ottoman army.