Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children (4 page)

Read Dark Eminence Catherine De Medici And Her Children Online

Authors: Marguerite Vance

every Frenchman at her feet/' Mentally she undoubtedly added that it would have been better if this child of the Guises had remained in her native Scotland. And Mary was not yet eight years old.

Why Elizabeth should have found it impossible to love her is not hard to understand. The princess adored her brother; from babyhood they had been inseparable companions; she was "ma soeur bienne aimee" Now suddenly she saw him, his cheeks scarlet, his eyes blazing, staring in open-mouthed worship at Mary Stuart, the little Scottish Queen who seemed to bewitch everyone. For the only time in her life, probably, lovely Elizabeth of Valois was jealous.

Chapter 3 CALLERS FROM SPAIN

THE months, the years flew, each bringing to the outside world of the sixteenth century its own peculiar hurdens of war, trial, torture and intrigue. Only as a wisp of smoke from a great conflagration may occasionally drift in at a distant window did the world's problems touch the royal children. Perhaps they sniffed the air curiously, inescapably aware that they were maneuvered about on the puppet stage of their days for some purpose which most of them understood only vaguely if at all,

Mary Stuart, after a few months at Saint-Germain, was sent to a convent for special religious training and then was returned to Saint-Germain where her education became a sort of tug of war with her uncles, the Duke of Guise and the Cardinal of Lorraine, on one side and her future mother-in-law, Catherine, on the other. As Mary and Elizabeth grew

older and their ages reached a more easily conformable level they had their lessons together and vied with each other in their Latin compositions.

Elizabeth was a good student but Mary was brilliant and often chided Elizabeth over her inferior work. So, an ancient record shows, these two girls had a sharp quarrel during which some unkind words were spoken on both sides and perhaps some bitter tears were shed. A few days later the merry little Queen of Scotland wrote her friend the following letter of reconciliation:

Maria Scotorum Regina, Elizabetae Sororl

I have heard from our master, my sister and darling, that now you are studying well, for which I greatly rejoice, and pray you to persevere in as the greatest good that can befall you in this world. For the gifts which we owe to Nature are of short duration, and age will deprive us of them. Fortune may likewise withdraw her favors: but that good thing which Virtue bestows (and she is wooed only by the diligent pursuit of letters) is immortal and will remain with us always.

Thus wrote the schoolgirl back in the sixteenth century.

So the schoolroom quarrels of the two girls were quickly over, but between Mary and Queen Catherine there existed an antagonism which one day caused Mary's Scottish temper to flare. Catherine, her maternal instinct to reprimand overcoming for the moment the realization that her young guest was a queen and she, Catherine, merely a queen consort,

corrected Mary sharply for some childish fault. Too late she saw her mistake when Mary, manners tossed to the winds, lashed out in royal fury.

'Til not be scolded by a merchant's daughter!'' shouted the little Queen as she ran from the room. Reared in an atmosphere of petty gossip, she had picked up the slur easily enough, probably abetted by her uncles, the Guises. But Catherine never forgave her.

However, Mary seemed incapable of bearing a grudge. Busy with her Latin, Greek, Spanish, French and Italian during the study hours, she was ringleader in the games the royal children played in the grand salon of the palace during the morning and afternoon recess periods,

In 1548 another princeling arrived in the nursery, little Louis, who became one of Mary's favorites but who died of croup two years later, about the time his brother Charles was born. Then came Henry, then Marguerite, and last of all, in 1554, Hercules, to be known as the Duke of Alengon.

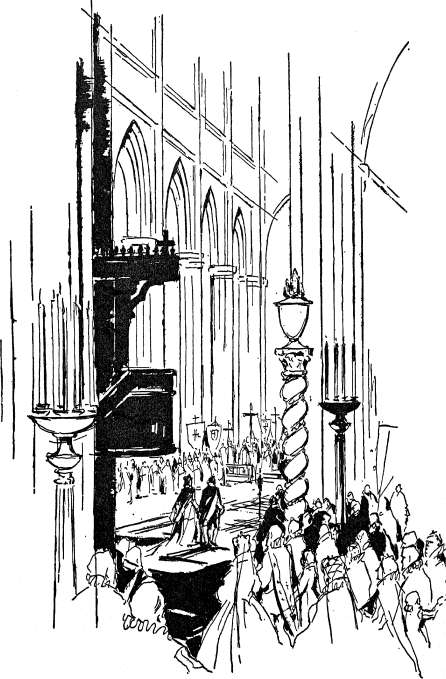

As time passed the Dauphin found himself becoming more and more attached to the pretty girl whom he now knew he would one day marry. She was beautiful and gay; she sang love rondels in a surprisingly rounded voice, accompanying herself on the lute; and young Francis, delicate lad that he was, did his utmost to make a good showing himself in the masculine arts. He begged his father to let him join him hunting and learned with agonizing effort to handle a heavy crossbow. He was a young boy deep in the turmoil of his first love, and when on an April morning in 1558 he knelt beside the lovely little Scottish Queen in Notre Dame, he

held his breath and let it out in great gulps lest his happiness overcome him and he break into noisy sobs of joy.

Escorted by his two younger brothers and the King of Navarre, a relative, and surrounded by princes of the blood, he awaited his bride at the west door of the Cathedral. King Francis escorted her, and an old history describes the fifteen-year-old girl as being "fair as unto a lily/' Her wedding gown was cloth of silver, its train borne by two young noblewomen, and on her head, that proud beautiful head one day to fall under the executioner's ax, she wore a crown studded with priceless jewels.

Behind her walked Catherine, Elizabeth, Claude, and little five-year-old Marguerite who pranced a little in her heavy velvet gown with its stiff Spanish ruff and false sleeves. Just outside the portals of the Cathedral, Francis slipped the wedding ring on Mary's finger, then hand in hand the young couple passed into the Sanctuary for the celebration of the Mass and the completion of the ceremony. The rest of the day and night was taken up with feasting and elaborate masquerades.

Elizabeth, her whole generous nature eager to accept unconditionally this fascinating young sister-in-law whom she did not like, danced the stately pavane with her, smiling gravely into the sparkling, provocative face. She had her reward when she caught a glimpse of Francis watching them and saw his look of beaming delight at their apparent mutual affection. The fourteen-year-old bridegroom wanted the whole world to love his bride.

Elizabeth, her mother's favorite daughter, had been trained

from babyhood in the art of politics. From the time she was ten years old she was permitted to sit beside her august mother—on a cushion at her feet—when the Queen granted audiences to visiting dignitaries, and so she learned not only some invaluable lessons in royal deportment but a great deal about what was transpiring in the world outside the fastness of her own sheltered life.

Among other things she learned of the religious hatreds dividing the world into warring camps, and because, unlike many children of royalty, she was deeply, sincerely religious, gentle and compassionate rather than ambitious, she heard with growing horror the stories of religious persecution com-

ing from many quarters. That her mother should sit quietly with folded hands, a half-smile on her lips, as the horrid tales were told filled the Princess with strange misgivings. Nor were the revelations all horrifying; some were only dull and rather puzzling. There was, for instance, the name of King Philip II of Spain, son of the greatest of all Hapsburg Emperors, Charles V. Between 1554 and 1558 the Emperor abdicated as head of the Holy Roman Empire, dividing his realm between his brother and his son, Philip II. As his portion Philip received Spain, Sicily, Naples, the Netherlands and Spanish America, a mighty empire, indeed. Elizabeth listened, uneasy yet curious, to the disquieting tales told of Philip's young son, Don Carlos, a boy about her own age whose name was being linked ever so discreetly with hers.

"Mother, Your Grace," she said one day when for a few moments they were alone, "Don Carlos methinks is not of a merry heart, is he?" It was only a few weeks before the wedding of Francis and Mary Stuart and somehow an atmosphere of romantic excitement pervaded the whole palace. Elizabeth sat back on her heels on the giant cushion beside her mother's chair, toying with the jeweled pomander hanging by its heavy gold chain from her waist. It smelled de-liciously of verbena and clove and crushed rose petals. "Is he?" she repeated.

Catherine turned from the documents she had been reading, her mind obviously still on their contents. Her child was asking a question, but what was it? "Is he what, child? And of whom are you speaking?" The scent of the pomander rose to her nostrils and, like any mother, she thought how like a

lovely flower was this girl looking up at her with such a trusting, artless expression. Just a little of Mary Stuart's laughing sophistication, little as she liked it, would have made the question easier to answer. The Queen Consort laid her hand for a moment on her daughter's head.

"Oh, I remember now, it was His Highness, Don Carlos, you were speaking of. No, he has not a merry heart. He—he is a sad young prince. Mayhap, well, mayhap a young bride with laughter in her heart could change him, and/' she added, "as he is heir to the greatest empire in the world there are doubtless many royal maidens eager for the chance."

She was tempted to enlarge on the theme, for it was very close to her heart, but she thought better of it. Why tell this hypersensitive child the truth: that Don Carlos was by any standards a monster, a mentally sick human being? that he delighted in torturing small animals and birds? that when angered he belabored his tutors and governors with any weapon on which he could lay his hands? that his favorite sport was to gather a company of young noblemen together and with them, riding four abreast, to gallop deliberately through the narrowest streets of the city, riding down anyone, regardless of age or condition, who happened to be in their path? Why needlessly torment her with this knowledge when, unless plans miscarried, she soon would be his bride?

"Nay, Elizabeth/' she repeated, "Don Carlos is not of a merry heart, but that is of no great concern. Your brother also is of a sober mien, yet who could be a more gallant prince than he? Her Majesty, the future Queen Dauphiness, will be blest, indeed, to have him for her husband,"

That had been several months ago. Now Francis was called the King Dauphin and the crowns of Scotland and France were united in his arms. Elizabeth, the romantic, gentle dreamer, tried to think of that brother as King with the grave responsibilities kingship entailed; tried to picture Mary, the gay, the beautiful, the naively flirtatious, as his wife. How was it all possible? And Don Carlos, the fabulous wealth of Spain, faraway Madrid. How should any of this touch her own life?

Strange, indeed, how in any age wholly unrelated incidents should be able to mold the course of lives distant both in time and place. For instance, in England Mary Tudor, half-sister of England's Queen Elizabeth, died knowing her handsome Spanish husband, Philip II of Spain, did not love her, never had loved her. Throughout Europe his name was dreaded as that of one of the most fanatical persecutors of heresy. He was suave, cultured, charming and cruel. He spent hours on his knees in prayer, made countless pilgrimages to shrines, and kept the fires of the Inquisition burning. Inconsistent, erratic, and now a widower, he bethought himself of a new wife. His half-sister-in-law, Elizabeth of England, he had always found fascinating, but Elizabeth was as staunchly Protestant as Philip was Catholic, so any thought of a marriage between them was out of the question.

However (and one wonders by what process of reasoning Philip reached this point), there was that beautiful French princess whose mother had sanctioned, nay encouraged her betrothal to his son, Don Carlos—Elizabeth of Valois. What of her? And what of Don Carlos? Philip un-