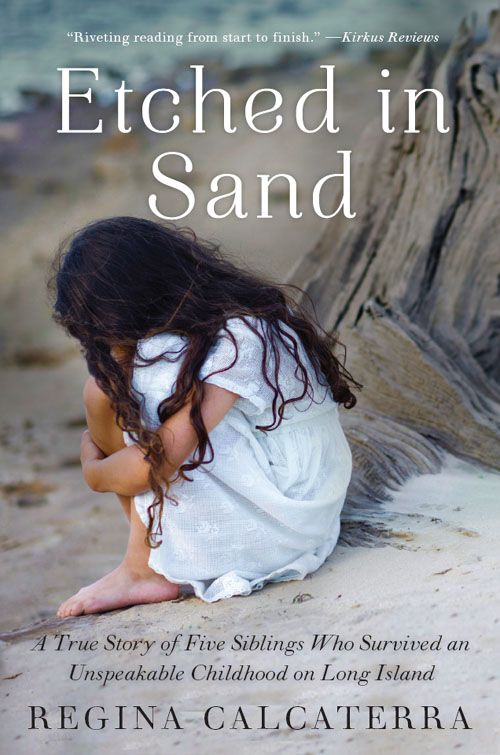

Authors: Regina Calcaterra

Etched in Sand

To Cherie, Camille, Norman, and Roseanne—

may we always continue laughing and dancing, together.

To the hundreds of thousands of children in the U.S.

who are either abused, in foster care, or homeless.

The journey is long and often dark but you must believe

in your light—you have so much to offer.

Contents

E

TCHED IN

S

AND

is the true story of the experiences I shared with my siblings from our childhood to the present day. My siblings consented to the publication of

Etched in Sand

and the use of their proper names in the forthcoming pages. However, some people’s names have been changed in order to protect their anonymity, including but not limited to past foster parents and relatives both living and deceased. Specifically worth noting is the name change of the character represented as my biological father, whom I refer to with the pseudonym of Paul Accerbi. For ease of description, my many social workers were consolidated into a few characters and are represented with pseudonyms as well. Also changed is the town that my younger siblings resided in when in Idaho.

I

HADN’T SEEN

New York City this still since 9/11. Lower Manhattan was a ghost town—there were no planes in the sky, no boats on the East River, no buses, no trains rumbling in the subway. This was Wall Street, normally the most bustling street in the world . . . but where I stood at the Wall Street Heliport, I was the only one present.

Because there was no traffic on my drive from Long Island to Manhattan, I was the earliest to arrive for the first official helicopter flyover after Hurricane Sandy. Soon everyone began to emerge from their vehicles: the governor of New York State, Andrew Cuomo; New York’s two United States senators, Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand; senior gubernatorial cabinet officials; and my colleagues from Nassau and Westchester Counties. We greeted one another in a manner both solemn and cordial, taking note of how a tragedy makes professional interactions seem much more personal. Wearing jeans, windbreakers, and boots, we exchanged details of the storm, our objective intensely clear. It was up to us to try and heal this region after Sandy’s destruction.

Within moments three military helicopters broke through the fog as assured as eagles. With the press and security now present, there were a couple dozen of us, all standing quietly as the copters whipped the vinyl of our coats and finally touched down on the pad. I felt a collective awareness among us that not even the roar of the propellers could cut through the heaviness of that morning. It struck me as one of the eeriest moments in my life: The silence was actually louder than the noise.

As the chief deputy executive of Suffolk County, I waited my turn to climb into the helicopter and by chance wound up in a seat that would give me a solid view of Long Island after we surveyed the damage in New York City. We took the military aviator’s instructions and placed the headphones over our ears. When the helicopter took off for Breezy Point in Queens, where a fire had ravaged a neighborhood during Sandy, the silence loomed again. Blocks of homes were charred. Families had lost everything. For me to have been managing the storm crises in Suffolk County while hearing the reports of how these Queens residents were trying to escape the area was one thing. Now to witness the damage where homes and lives had been destroyed was a completely surreal moment.

My heart pounded as we neared Suffolk and I prepared to address my county’s devastation for this group of elected officials I respected so greatly. “Which town in Suffolk had the most damage?” one of them asked.

I hurried to push the microphone button on the headset as our aviator had shown us. “Lindenhurst,” I answered. The group nodded and gazed back out the window, as though they understood why Lindenhurst holds a special significance to me: It’s where I was born. It’s also the place where three decades later, I learned my background from family I’d never known existed. My mother left behind scorched earth with the same totality that Mother Nature had swept my island. For years, Suffolk County transported me back to the pain and darkness my four siblings and I endured throughout our fatherless childhoods with a profoundly troubled mother. Now, as I examined it from the sky, my emotions swelled with a love for this place—how the experiences of growing up here made me who I am. Hovering above as a leader in the aftermath of Sandy struck me deeply. Aside from the love I shared with my siblings, this county was our only sense of home—a place that did its best to protect us from the unpredictable. I never could have imagined that one day I’d be called on to return the same security.

W

HAT DREW ME

to a career in public service was my appreciation for government’s purpose: It’s the body that decides who receives which resources, and how much of them. My childhood on Long Island gave me a very personal awareness for how people in power can impact the lives of others. Growing up here I faced extraordinary struggles that would have tested any child’s strength and endurance. Somehow, with optimism and determination, my siblings and I could usually manage to find someone who was willing to lift us to help.

My cast of resolute characters is composed of my older sister Camille, who is forever my closest confidante; and our three siblings—Cherie, the eldest, who found escape from our childhood in a teen marriage; Norman, fourth in birth order just behind me; and our youngest sister, Rosie. As a scrappy pack of homeless siblings wandering the beach communities of Long Island, sometimes we’d sneak off to the Long Island Sound or the Atlantic’s shore—the wild, windy places where it didn’t matter who we were, what we wore, or how tousled we appeared. With our hands and empty clamshells as our tools, we’d build sand castles by the water, or etch out all five of our names

Cherie Camille Regina Norman Rosie

and enclose each with a heart. We’d run, squealing, as the waves roared upon the shore and rolled back in rhythm, unsentimentally washing away our work. Then we’d run back toward the water and create it all anew.

We didn’t know it then, but that persistence would become the metaphor to predict how we’d all choose to live our lives. No accomplishment has taken place without trial, and no growth could have occurred without unwavering love. This is the story of how it took a community to raise a child . . . and how that child used her future to give hope back.

Suffolk County, Long Island, New York

Summer 1980

T

HE AREA WHERE

we live sits between the shadows of the cocaine-fueled, glitzy Hamptons estates and New York City’s gritty, disco party culture. Songs like Devo’s “Whip It” and Donna Summer’s “Bad Girls” blast through the car courtesy of WABC Musicradio 77, AM. Gas is leaded and the air is filthy.

Long Island lacks a decent public transportation system—to get anywhere, you need either a car or a good pair of shoes. Our shoes aren’t the best.

Our car is worse.

My mother’s thick arm rests on the driver’s-side window ledge of her rusty, gas-guzzling Impala—the kind you buy for seventy-five dollars out of a junkyard. Her wild hair blows around the car as she flicks her cigarette into the sticky July morning. The ashes boomerang back in through my window, threatening to fly into my eyes and mouth in frantic gusts. Squinting tightly and pursing my lips hard, I know better than to mention it.

My seven-year-old baby sister, Rosie; our brother, Norman, who’s twelve but still passes for an eight-year-old when we sneak into movie theaters; and me—Regina Marie Calcaterra, age thirteen (personal facts I’m well accustomed to giving strangers, like social workers and the police)—are smooshed into the backseat. Like most of our rides, the car suffers from bald tires, broken mirrors, and oil dripping from the motor. If I lift up the mats, I can see the broken pavement move beneath us through the holes in the rear floor.

We rarely travel the main roads like the Southern State, Sunrise Highway, or the Long Island Expressway. For Cookie—that’s what we call my mom—the scenic route is the safest because she’s always avoiding the cops. Cookie has more warrants out on her than she has kids. And there are five of us.

Her offenses? Where to start? She’s wanted for drunk driving; driving with a suspended license and an unregistered vehicle; stolen license plates; bounced checks to the landlord, utility company, and liquor store totaling hundreds of dollars; stealing from her bosses (on the rare occasion she gets work as a barmaid); and for our truancy. And if there were such a thing as a warrant for sending her kids to school with their heads full of lice, we could add that to the list, too!

In the car, we don’t speak. It’s not by choice—it’s actually impossible to hear one another above the loud grunting of the Impala and its broken muffler. Embarrassed by the car’s belches, I slump down in my seat. In the front seat next to Cookie, my older sister Camille’s doing pretty much the same thing . . . but if our mother detects our attitude, we’ll find ourselves suffering nasty bruises. The only comfort is the physical space we now have to actually fit in the car without piling on top of one another as we had to for years. That’s thanks to the fact that, at age seventeen, our oldest sister, Cherie, has finagled an escape by moving in with her new husband and his parents, since she’s expecting a baby soon.

In the backseat, Rosie, Norman, and I stay occupied, scratching our bony, bug-bitten legs and comparing who has the most bites and biggest scabs. We take turns pointing to them as Rosie uses her fingers as scorecards to rate them on a scale of one to ten. There’s never really a winner . . . we’re all pretty itchy.

None of us bothers hollering to ask where we’re going. With all our belongings packed in garbage bags in the trunk, we know we’re headed to a new home. Our short-term future could take many forms—a trailer, a homeless shelter, the back parking lot of a supermarket, in the car for a few weeks, in Cookie’s next boyfriend’s basement or attic, or dare we dream: an apartment or house. We know better than to expect much—to us, running water and a few old mattresses is good living. We’ve managed with a lot less.

Most girls my age idolize their sixteen-year-old sisters, but Camille is my cocaptain in our family’s survival. She’s the only person in my life who’s totally transparent, and we need each other too much for any sisterly mystique to exist. For years, the two of us have worked to set up each new place so that it feels at least something like a home, even though we never know how long we might stay there. We just rest easier knowing, at nightfall, that the younger ones have a safe spot to rest their heads. Together. Without Cookie. If we can control that.

Cookie puts the brakes on our wordless games when she pulls into a semicircular driveway, gravel crunching under the tires. We’re met by the image of a gray, severely neglected two-story shingled house surrounded by dirt, dust, and weeds. There are no bushes, no flowers, no greenery at all; but the lack of landscaping draws a squeal from me. “No grass!”

Rosie and Norman smile and nod in agreement, understanding this means we won’t be taking shifts to accomplish Cookie’s definition of “mowing the lawn”—using an old pair of hedge clippers to cut the grass on our hands and knees. Camille and I usually cut the bulk of the lawn to protect the little ones from the blisters and achy wrists.

Cookie turns off the ignition and coughs her dry, scratchy smoker’s cough. “This is it,” she announces. “Sluts and whores unpack the car.” Then she emits a loud, sputtering, hillbilly roar that never fails to remind me of a malfunctioning machine gun. As usual, she’s the only one who finds any humor in the degrading nicknames she’s pinned on her daughters.

I gaze calmly at the facade before me. It’s a house . . . our house. Even if it ends up being only for a few days, I’m relieved that my siblings and I won’t be separated.

Since the interior car-door handle is missing, exiting the car is always an occasion for embarrassment. I take my cue as Cookie reaches out her window, pulling up the steel tab that opens her door with her right hand while she pushes with her left shoulder from the inside. It’s my job to step out and pull the exterior driver’s-side door handle for her, especially when she’s too drunk to get the door open on her own. This normally results in me falling on my bony bottom as the heavy steel door comes barreling out toward me from my mother’s force. I quickly jump straight up like Nadia Comaneci at the Montreal Olympics—landing with locked legs and arms extended skyward—and look back at the three little judges in the car to rate my performance. As always, this leads to giggles from Rosie and Norman and an

I feel your pain

wince from Camille, whose behind is just as scrawny as mine.

Since my dismount lacks originality, my score is always the same. Rosie is the most generous, flashing ten stretched-out fingers. Norman offers an underwhelmed five; Camille gives me two thumbs-up, which from her is equal to a ten.

Cookie usually just snorts in my direction, but not this time.

Today she’s in a hurry. She lurches out of the driver’s seat while the car lets up beneath her weight. We all watch her hulking five-foot-two, size-18 figure stagger around the front of the car and toward the gray house with a six-pack of Schlitz beer stuffed under her arm. I rest my hands on my hips and look around, relieved there are no neighbors outside.

The dampness of Cookie’s white Hanes T-shirt exposes her quadruple-D over-the-shoulder-boulder-holders and, for God’s sake, too much of the boulders—they’re struggling to stay in the cups. Her appearance gives me a sudden urge to cover the little ones’ eyes, but by now, for them, the sight of our mother’s unmentionables holds no shock . . . instead Norman and Rosie are shaking in silent giggles. An old pair of cutoff jean shorts that should be six inches longer and wider in the thighs completes her look. She peers inside the house’s window from the front stoop then pushes open the door, which obviously bears no lock. Hastily she turns and waves—“Come on, kids!”—signaling urgency for us to unpack the car.

While our younger siblings remain in the backseat, Camille leans over from the front passenger side of the car, reaches down toward the steering wheel, and fingers the keys Cookie left in the ignition. She looks back at me, and we understand the significance of the keys’ position. As usual, Cookie doesn’t plan to stick around our new home long.

We spring into action. The faster we unpack the car, kids and all, the quicker our mother will head out on another long binge. We have to move with speed, convincing Cookie our motive is all about setting up our new home. She’d beat us senseless if she ever found out how eager we are to get rid of her.

Through the backseat window I peek at Norman, who’s used to my Moving Day choreography. “Take her inside with you,” I tell him. He helps Rosie climb out from the middle; his brown, bowl-cut hair uncombed, his face calm. Camille and I work hard to raise him like one would raise any curious, carefree, twelve-year-old boy. His sweet, slanted brown eyes are barely visible below his uneven haircut, and I pledge him a silent promise:

I’ll find new scissors for next time.

Sometimes I reason that if I’ve gotta raise a kid who’s only a year and a half younger than I am, then surely I have the right to experiment my self-taught salon techniques on him . . . but that Dorothy Hamill look on a preteen boy is just plain cruel.

Norm shuffles into the house with Rosie, still wearing her pink pajamas, close behind. I pause from unloading the car to take in her presence; a little flash of life scampering barefoot across this gray scene. Her innocence pierces my heart.

After they’re inside, Camille scurries around with the keys and opens the trunk, then passes them off to me so I can insert them back in the ignition. We’re careful to conduct the move-in with no detail that could keep our mother here longer than absolutely necessary. She’s probably inside having a drink right now, which could be enough to disorient her from recalling where she put her keys.

The trunk of the car is stuffed with green garbage bags that Camille, the kids, and I packed: There’s a bag filled with each of our clothes, a near-empty bag with our collective toiletries (half a bar of soap; an old toothbrush we share; a bottle of peroxide; and a dull, rusty razor), a bag stuffed with old towels, and a bag packed with all the groceries we cleaned out of our last place. We have a prevailing unpacking rule: You unpack the bag you pick. This way we can’t fight about who unpacks Cookie’s clothes. I can tell that I’m carrying our nonperishables, which I always make sure travel with us: vinegar, mustard and ketchup, and other essentials like coffee, flour, sugar, and powdered milk. From the other side of the trunk, I can smell Camille’s cargo—it reeks of stale cigarettes. She cringes despairingly. “Finders keepers,” I tell her. “I have kitchen duty, you’re on Cookie duty. Just be glad she likes you better.”

It’s always been clear that Cookie prefers my older sisters to me. Because we all have different fathers, our last names are as varied as our first names. Cherie is the luckiest. She was named after the Four Seasons’ song “Sherry” that hit number one on the

Billboard

charts in 1962, the year she was born. (However, Cookie found the French spelling,

Cherie

, to be much more sophisticated.) My mother named her second daughter after herself—Camille. Her famous line is that she named me Regina because it means

royalty

. “I was right,” she always says, “because you turned out to be a royal pain in my ass.” Norman was named after his father, and Roseanne was named after my great-grandmother, Rosalia KunaGunda Maskewiez, whom none of us has ever met.

Camille and I shuffle the bags inside. “Whoa,” Camille says. “This place actually has furniture.”

Rosie’s climbed onto a sofa in front of the bay window, and is stretched across it with her feet as far as they can go, mimicking Cookie’s position on the couch across the room. “There’s even a TV!” she exclaims, pointing to the large unit in the corner.

“Wow,” I tell her, crouching down and twisting her pigtail around my finger. “Did you try it out?”

“Yeah, it works!”

I smile and steal a glance at Cookie. She looks pleased with herself, smoking a cigarette with her right arm wrapped across her waist. Mother of the freakin’ year.

“My room is next to the kitchen,” she says to no one in particular, then waves her cigarette to a staircase behind her. “You kids can fight it out upstairs.”

I find three rooms on the top floor. The room to my left is filled with a cot and an old wooden desk. All the desk drawers are missing handles; a broomstick holds up the desk where a leg once stood. The room straight ahead has two windows overlooking the side yard and part of the extension that houses the room Cookie claimed. It has a mattress and a box spring, but no frame. This will work, I calculate, because Norman and Rosie can sleep here. One can have the mattress and the other can have the box spring—kind of like two separate beds.

Although there are no pillows or blankets in sight, this arrangement is an improvement over sleeping three in the backseat or in an open car trunk, which we’ve done before. I peer around into the narrow, one-windowed room to the right, which features a mattress and box spring atop a real metal bed frame. Viewing farther inside I find a shelf for clothes. This will be Camille’s room. She’s the oldest one here and deserves a real bed.

I take the room with the cot, resting my garbage bag on the floor and digging out my plastic Jesus figurines. This will signal to my siblings that this room is mine.

When I turn back toward the door, Norman brakes from running down the hall to stop in Camille’s room and looks out over the gray, gravel front yard.

“You like the new place?” I ask him.

“Like it? I love it! Think I can have this room?”

“Nope, it’s Camille’s. You and Rosie get to share the room at the end of the hall.”

He runs there, pokes his head inside, smiles back at me, and takes off downstairs.

“I’ll set your room up when Cookie leaves,” I yell after him. “Dig out Trouble so you and Rosie can play while we clean.”

I find Camille at the car, unloading Norman and Rosie’s stuff. “Cookie’s in her bedroom,” I mutter.

“She better not pass out.”

“I made sure she won’t. Norman’s setting up Trouble outside her bedroom door.”

“Genius!” The popping bubble in the middle of the board game, combined with the kids’ chatter, will be enough to drive her out.