Read Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking Online

Authors: Fuchsia Dunlop

Tags: #Cooking, #Regional & Ethnic, #Chinese

Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking

For Leonie

鋤 禾 日 當 午

汗 滴 和 下 土

誰 知 盤 中 飯

粒 粒 皆 辛 苦

The farmer hoes his rice plants in the noonday sun

His sweat dripping on to the earth

Who among us knows that every grain of rice in our bowls

Is filled with the bitterness of his labor.

李 紳

Li Shen

CONTENTS

If you are going to follow links, please bookmark your page before linking.

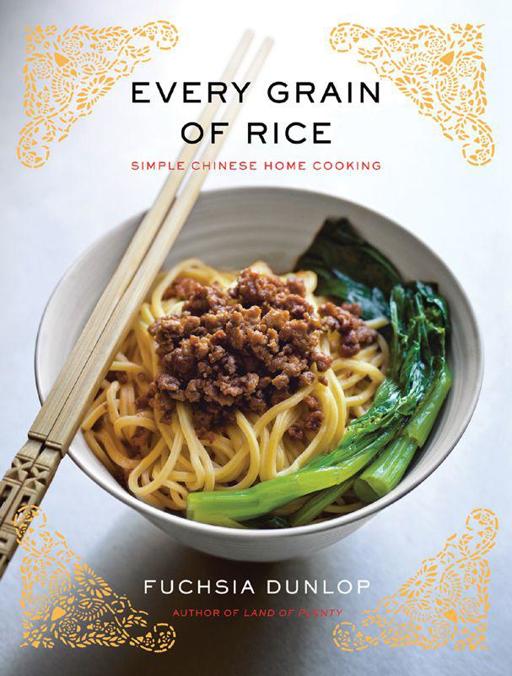

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

INTRODUCTION

BASICS

COLD DISHES

TOFU

MEAT

CHICKEN & EGGS

FISH & SEAFOOD

BEANS & PEAS

LEAFY GREENS

GARLIC & CHIVES

EGGPLANT, PEPPERS & SQUASHES

ROOT VEGETABLES

MUSHROOMS

SOUPS

RICE

NOODLES

DUMPLINGS

STOCKS, PRESERVES & OTHER ESSENTIALS

GLOSSARY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INDEX

COPYRIGHT

The Chinese know, perhaps better than anyone else, how to eat. I’m not talking here about their exquisite haute cuisine, or their ancient tradition of gastronomy. I’m talking about the ability of ordinary Chinese home cooks to transform humble and largely vegetarian ingredients into wonderful delicacies, and to eat in a way that not only delights the senses, but also makes sense in terms of health, economy and the environment.

Not long ago I was invited to lunch in a farmhouse near Hangzhou, in eastern China. In the dining room, the grandmother of the household, Mao Cailian, had laid out a selection of dishes on a tall, square table. There were whole salted duck eggs, hard-boiled and served in their shells, fresh green soy beans stir-fried with preserved mustard greens, chunks of winter melon braised in soy sauce, potato slivers with spring onion, slices of cured pig’s ear, tiny fried fish, the freshest little greens with shiitake mushrooms, stir-fried eggs with spring onions, purple amaranth with garlic, green bell pepper with strips of tofu, and steamed eggs with a little ground pork, all served with plain steamed rice. Most of the vegetables on the table were home-grown and the hen’s eggs came from birds that pecked around in the yard.

I’ll never forget that meal, not only because it was one of the most memorably delicious that I have had in China, but also because it was typical of a kind of Chinese cooking that has always impressed me. The ingredients were ordinary, inexpensive and simply cooked and there was very little meat or fish among the vegetables, and yet the flavors were so bright and beautiful. Everything tasted fresh and of itself. Mrs. Mao had laid on more dishes than usual, because she was entertaining guests, but in other respects our lunch was typical of the meals shared by families across southern China.

European visitors to China since the time of Marco Polo have been struck by the wealth of produce on sale in the country’s markets: fresh fish and pork, chickens and other birds, exquisite hams and an abundance of vegetables. The rich variety of ingredients, especially vegetables, in the Chinese diet is still striking. I remember researching an article about school dinners in China in the wake of Jamie Oliver’s campaign to improve them in Britain. I came across a group of children at a Chengdu state school lunching, as they did every day, on a selection of dishes made from five or six different vegetables, rice and a little meat, all freshly cooked and extremely appetizing.

More recently, walking around the streets of Beijing, I couldn’t help noticing the extraordinarily healthy lunches being eaten by a team of builders outside a construction site. They were choosing from about a dozen freshly cooked dishes made from a stunning assortment of colorful vegetables, flavored, in some cases, with small amounts of meat, and eating them with bowls of steamed rice.

Across the country, a vast range of plant foods are used in cooking. There are native vegetables such as taro and bamboo shoots; imports that came in along the old silk routes from Central Asia such as cucumber and sesame seeds; chillies, corn, potatoes and other New World crops that began to arrive in the late sixteenth century; and more recent arrivals such as asparagus that have become popular in China only in the last few decades. And aside from the major food crops, there are countless local and seasonal varieties that are little-known abroad, such as the Malabar spinach of Sichuan, a slippery leaf vegetable used in soups; the spring rape shoots of Hunan which make a heavenly stir-fry; and the Indian aster leaves that are blanched, chopped, then eaten with a small amount of tofu as an appetizer in Shanghai and the east of China.

Of course, food customs are changing as fast as everything else in China. In the cities, people are eating more meat and fish, dining out more frequently and falling for the lure of Western fast food. Rates of obesity, diabetes and cancer are rising fast. Younger people are forgetting how to cook and I wonder how some of them will manage when their parents are no longer around to provide meals for the family.

The older generation and those living in the countryside, however, still know how to cook as their parents did. They use meat to lend flavor to other ingredients rather than making it the center of the feast; serve fish on special occasions rather than every day; and make vegetables taste so marvellous that you crave them at every meal. It is interesting to see how modern dietary advice often echoes the age-old precepts of the Chinese table: eat plenty of grains and vegetables and not much meat, reduce consumption of animal fats and eat very little sugar. In our current times of straitened economies, overeating and anxiety about future food supplies, traditional Chinese culinary practices could be an example for everyone.

In the past, of course, it was economic necessity that limited the role of meat in the Chinese diet, but, coupled with the eternal Chinese preoccupation with eating well, this habit of frugality has encouraged Chinese cooks to become adept at creating magnificent flavors with largely vegetarian ingredients. In Chinese home cooking, a small quantity of meat is usually cut up into tiny pieces, adding its savoriness to a whole wokful of vegetables; while dried and fermented foods such as soy sauce, black beans and salt-preserved or pickled vegetables—seasonings I’ve come to think of as magic ingredients—bring an almost meaty intensity of flavor to vegetarian dishes.

One of the richest aspects of Chinese culture, arguably, is the way so many people know how to eat for health and happiness, varying their diets according to the weather and the seasons, adjusting them in the light of any symptoms of imbalance or sickness and making the most nutritious foods taste so desirable; and yet in China, people generally see this wealth of knowledge as unremarkable. I’ve lost count of the number of times that Chinese chefs and domestic cooks have told me of their admiration for the “scientific” approach of Western nutrition, without seeming to notice how confused most Westerners are about what to eat, or to consider how much the time-tested Chinese dietary system might have to offer the world.

Chinese cooking has something of a reputation in the West for being complicated and intimidating. It’s true that banquet cooking can be complex and time-consuming, but home cooking is generally straightforward, as I hope this book will show. Keep a few basic Chinese seasonings in your larder and you can rustle up a delicious meal from what appear just to be odds and ends. Not long ago, I invited a friend back for supper on the spur of the moment and had to conjure a meal out of what felt like nothing. I stir-fried half a cabbage with dried shrimps, and leftover spinach with fermented tofu; made a quick twice-cooked pork with a few slices of meat I had in the freezer; and steamed some rice. The friend in question is still talking about the meal. Cooking a few bits and pieces separately, with different seasonings, made a small amount of food seem exciting and plentiful.

The recipes in this book are a tribute to China’s rich tradition of frugal, healthy and delicious home cooking. They include meat, poultry and fish dishes, but this is primarily a book about how to make vegetables taste divine with very little expense or effort, and how to make a little meat go a long way. Vegetables play the leading role in most of the recipes: out of nearly 150 main recipes, more than two-thirds are either completely vegetarian or can be adapted to be so, if you choose. Some of the recipes call for more unusual Chinese vegetables that may require a trip to a Chinese or Asian supermarket, but many others demand only fresh ingredients widely available in the West. I have avoided complicated recipes that are more suited to restaurants than home cooking, as well as deep-frying, with a few delicious exceptions.

A large number of recipes come from the places I know best: Sichuan, Hunan and the southern Yangtze region. (Cooks from Sichuan, my first love in terms of Chinese food, are particularly skilled at creating cheap, simple dishes that are extravagantly savory.)

Other recipes are from Hong Kong, Guangdong, Fujian and other regions that I’ve visited. There is a definite southern bias in the selection, partly because I’ve spent most time in southern China and partly because southerners, with the diversity of fresh produce available to them all year round, have the most varied and exciting ways with vegetables. I’ve included some simplified versions of classic recipes from my previous books, and a few unmissable favorites in their original forms.

Chinese home cooking is not about a rigid set of recipes, but an approach to cooking and eating that can be adapted to almost any place or circumstance, so I hope that this book will serve as a collection of inspiring suggestions as much as a manual. Many of the cooking methods and flavoring techniques can be applied to a wide range of ingredients. I’ve made suggestions for alternatives in many recipes, but feel free to use your imagination and improvise with whatever you can find in your fridge or cupboard. And although I’ve tested all the recipes with precise amounts of ingredients and seasonings, many are so simple that quantities are not critical: you can add a little more or less of this and that as you please, once you have become familiar with the basic techniques. And, of course, please do use the best, freshest ingredients you can find.

With all the fuss over the Mediterranean diet, people in the West tend to forget that the Chinese have a system of eating that is equally healthy, balanced, sustainable and pleasing. Perhaps it’s the dominance of Chinese restaurant food—with its emphasis on meat, seafood and deep-frying as a cooking method—that has made us overlook the fact that typical Chinese home cooking is centered on grains and vegetables.

Culinary ideas from other parts of the world, such as Middle Eastern hummus and halloumi, Thai curry pastes, Italian pasta sauces and North African couscous have already entered the mainstream in many parts of the West. I’d like to see Chinese culinary techniques and ingredients inspiring people in the same way to make the most of local ingredients wherever they are. I regularly use Chinese methods to cook produce I’ve bought in my local shops and farmers’ markets. I have given purple-sprouting broccoli the Cantonese sizzling oil treatment, slow-cooked English rare breed pork in the Hangzhou manner with soy sauce, sugar and Shaoxing wine, steamed Jerusalem artichokes with Hunanese fermented black beans and chilli and prepared mackerel I caught on holiday in Scotland with soy sauce and ginger; all to splendid effect. Sesame oil, soy sauce and ginger may already be on your shopping list and mainstream supermarkets are now stocking Chinese brown rice vinegar and cooking wine; just add Sichuanese chilli bean paste and fermented black beans and you will open up whole new dimensions of taste.