Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (39 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

Captain von Falckenberg let himself drop down into his tank, pulling the hatch shut behind him. "Forward!" he called to his driver. "To the crossroads!" Second Lieutenant Köhler of 2nd Troop had likewise watched Fromme's axe duel and roared forward to support him. He moved into position on the right of Fromme's troop and at once joined the action. His four Mark III tanks were just in time to take the next lot of Soviet tanks in the flank. At nightfall eighteen tanks lay disabled in front of Falckenberg's sector. The Soviet counterattack south-east of Lake Peipus had had its back broken. The road to Pskov was clear.

In an eastward sweep by the combat group Westhoven the reinforced 1st Rifle Regiment drove on as far as the airfield of Pskov, which had evidently been abandoned in a hurry by a senior Soviet Air Force headquarters. The maps in the situation room revealed some interesting information about the enemy's intentions. Major-General Krüger captured a bridge in the Tserjoha sector intact, with a surprise coup by 1st Rifle Brigade. The town of Pskov, by then in flames, was taken by 36th Motorized Infantry Division in a frontal attack on 9th July.

Twenty miles to the south-east the 6th Panzer Division had also broken through the Stalin Line. Twenty heavy pillboxes had been cracked by the sappers and strong enemy armour thrown back. Hoepner's Panzer Group had thus reached its first great objective. The Russian barrier south of Lake Peipus had been pierced, the Russians' southern exit from the Baltic area had been blocked, and the jumping-off position for an attack on Leningrad had been gained.

The swift blow against the city was to be struck in a northerly direction across the narrow neck of land between Lakes Ilmen and Peipus. The aim was still to 'take' Leningrad—

i.e.,

to capture it. The operation was to be supported by the Finnish Army driving from the north across the Karelian Isthmus and simultaneously attacking east of Lake Ladoga; in this way the city with its 3,000,000 inhabitants was to be sealed off from the north and east against the arrival of reliefor attempted breakouts from within.

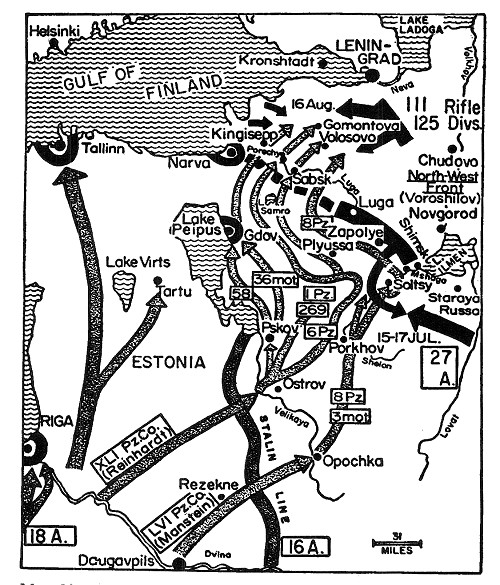

Under the terms of their general orders the 4th Panzer Group intended to make Reinhardt's Panzer Corps drive towards Leningrad along the Pskov-Luga-Leningrad road, and to send Manstein's Panzer Corps along the second road to Leningrad, that from Opochka via Novgorod. Those two great roads were the only ones leading through the extensive marshy area which shielded Leningrad towards the south and south-west.

On 10th July 1941 the Panzer Group mounted its attack along the whole front. The LVI Panzer Corps, which had pierced the Stalin Line at Sebezh on 6th July with the motorized "Death's Head" SS Infantry Division, and after hard fighting had taken Opochka on the Velikaya river, was now to make an outflanking movement to the east and, advancing via Porkhov and Novgorod, cut the big lateral road from Leningrad to Moscow at Chudovo. The 8th Panzer Division and the 3rd Motorized Infantry Division were employed in the front line. Their task was to advance across very difficult wooded ground.

The XLI Panzer Corps, with 1st and 6th Panzer Divisions in front and 36th Motorized Infantry Division behind, moved off along the main road via Luga. To begin with enemy resistance was confined to rearguard actions. The enemy was giving ground. Had the Russians really given up in the north? Nothing of the kind. Voroshilov was not prepared to abandon Leningrad or the Gulf of Finland. On the very next day the advance of Reinhardt's Panzer Corps was slowed down. Its divisions had got into difficult swampy forest terrain which offered the enemy excellent opportunities for defence.

When General Reinhardt tried to move his tanks and armoured infantry carrier battalions, in particular the combat groups Krüger and Westhoven of 1st Panzer Division, off the Pskov—Luga road for an outflanking action, with a view to cracking the Russian roadblocks from the rear, he was to discover that to the right and left of the road the ground was swampy and virtually impassable for armour.

The 6th Panzer Division too had to be brought back from its wretched secondary roads to the Corps' main road of advance behind the 1st Panzer Division because its vehicles were continually getting stuck. No large-scale operations were possible. The tanks lost their advantage of mobility and speed. On 12th July the Corps' offensive ground to a standstill along the Zapolye-Plyusa line.

Enemy resistance was even stronger in front of Manstein's Corps—

i.e.,

on the right wing—where in accordance with High Command orders the main weight of the attack was to be concentrated. It was found that the Russians had built up a new fortified zone covering Leningrad and Shimsk on the western shore of Lake Urnen, and along the Luga river as far as Yamberg on the Narva. The town of Luga, as a bridgehead on the Daugavpils-Leningrad highway, was the keystone of the position and had been strongly fortified.Ground and aerial reconnaissance of 4th Panzer Group, on the other hand, discovered that the left wing, on the lower Luga, was held by weak enemy forces only. Clearly, because of the bad roads there, the Russians did not expect an attack. The only other enemy force of any size was on the eastern shore of Lake Peipus, near Gdov.

Colonel-General Hoepner was faced with a difficult decision: was he to stick to his orders and keep the main weight of his attack on the right, in the direction of Novgorod, and allow Reinhardt's Panzer Corps to batter their heads against the strong defences at Luga, or should he make a bold left turn towards the lower Luga, strike at the enemy where he was weak, and in this way promote an attack on Leningrad from the west, parallel to the Narva-Kingisepp- Krasnogvar-deysk railway?

Hoepner decided on the latter alternative. He switched the 1st and 6th Panzer Divisions to the north under cover of the combat group Westhoven, which was fighting east and north of Zapolye, and replaced them with infantry divisions along the main road to Luga, The two Panzer .divisions, followed by the 36th Motorized Infantry Division, then moved off to the north, on 13th July, over difficult roadless terrain.

In a forced march of 90 to 110 miles the three motorized divisions struggled painfully forward, in some places dangerously extended and in others crowded together on a single boggy road, struggling hard to keep up with their vanguards. The small bridges collapsed. The road became a swamp. Sappers had to build wooden causeways.

Reconnaissance detachments and covering groups of motor-cyclists, Panzerjägers, and forward batteries scrambled through the mud along the flanks in order to take up covering positions in the most exposed places or to ward off repeated enemy attacks mounted from out of the vast marshes. But the risky manœuvre succeeded. The spearhead of 6th Panzer Division—the advanced detachment of 4th Rifle Regiment reinforced by armour and artillery under the command of Colonel Raus—took Pore-chye on 14th July. The two bridges fell undamaged into the hands of a special detachment of the "Brandenburg" Regiment—so much was the enemy taken by surprise.

Map 10. The operation of Army Group North from the end of June to the middle of August 1941. The Stalin Line had been pierced. Hoepner's Panzer Group was striking towards Leningrad across the lower Luga.

On the same day 1st Panzer Division reached the Luga river at Zabsk with the reinforced Armoured Infantry Carrier Battalion of 113th Rifle Regiment under Major Eckinger, and by 2200 hours had established a bridgehead on the eastern bank against enemy opposition. The ford was extended, and during the same night the bridgehead was enlarged and the bulk of the 113th Rifle Regiment was brought up. In this way 1st Panzer Division succeeded in holding Zabsk with the combat group Krüger against fierce enemy counter-attacks throughout 15th July. The bridge, however, had been destroyed. But on the following day the bridgehead was further consolidated. The enemy grouping on the western flank of the 4th Panzer Group, on Lake Peipus near Gdov, was smashed by the 36th Motorized Infantry Division and the 58th Infantry Division.

The obstacle of the lower Luga was overcome. A springboard for the final assault had been established 70 miles from Leningrad. In two extensive bridgeheads the riflemen and armour of Reinhardt's Corps were standing by for the

assault. The Soviets had been taken completely by surprise by this operation. At first they had no forces of any importance opposite the new German front line. With hurriedly collected formations, including officer cadets from Leningrad, they tried in vain to clear up the bridgeheads. However, the German troops succeeded not only in repelling all attacks, in savage fighting, but, indeed, in extending their jumping-off positions and in improving their supply roads. Thus they awaited the order to resume their attack. Leningrad lay before them, unprotected, only two days' march away.

But now the same tragedy occurred on the northern front, before Leningrad, that we witnessed at Army Group Centre after the swift capture of Smolensk. The German High Command held back Hoepner's tanks in the Luga bridgeheads for three weeks. Three long weeks. Why? Why was not the focus of the offensive formed on this sector? Why was advantage not taken of the chance that offered itself? Once again the High Command bureaucracy frustrated a swift and very probably successful blow against a major objective.

Hitler and the Wehrmacht High Command had made up their minds about having the main weight of the operation on the right—in other words, Leningrad was to be taken by a wide outflanking attack from the south-east. The flank cover for the operation presumably was to be provided by Sixteenth Army coming up from the west; for the time being the gap between it and 4th Panzer Group was covered by the two divisions of LVI Panzer Corps alone.

In this way the Russian divisions streaming back from the Baltic countries were to be caught in a huge arc whose flank would be ideally protected by the marshy river Volkhov. It was a good plan. But it contained one important mistake: because of the wooded and swampy ground on the right of the offensive the tanks could not be used to full advantage. After all, that was why Hoepner had switched his XLI Corps to the left. Some strong infantry divisions, artillery, and air force units remained on the right wing, but manœuvrable armoured forces were lacking because the 8th Panzer Division and the 3rd Motorized Infantry Division were tied down between 15th and 19th July in bitter fighting with strong formations of three to five Soviet Corps.

The newly created focus of attack on the left on the lower Luga, on the other hand, had armour, bridgeheads, jumping- off positions, and no enemy in front of it—but it lacked infantry divisions to cover an extended armoured thrust towards Leningrad. Hoepner tried everything to get Manstein's Corps to the north to make up for the infantry he himself lacked and which it would take too long to bring up from the rear. But Army Group would not or could not stand up to the Fuehrer's headquarters. There it was held that Reinhardt's forces were too weak to make the attack on Leningrad by themselves. Further reinforcements were therefore sent to the right wing of the offensive, to Lake Ilmen, where fighting continued under great difficulties.

Why, Colonel-General Reinhardt rightly asks to-day, should it have been impossible to switch Manstein's Corps to his wing? Would it not have been more correct to transfer the main weight of the offensive to the left, to block the narrow passage at Narva as quickly as possible, and then to wheel east and strike the enemy, who was still holding out along the middle Luga, in the rear with strong forces?

When Guderian found himself in a similar situation on the Dnieper before Smolensk Field-Marshals von Kluge and von Bock let him have his own way. Probably, if Kluge or Bock had been in Leeb's place they would have allowed Reinhardt to move off too. But Leeb was no von Bock. Admittedly, he toyed with the idea of giving Hoepner the green light, and he tried to get the High Command directive "main weight on the right" rescinded—but, in fact, he neither did the former nor achieved the latter. Thus a fatal tug-of-war ensued and continued for weeks on end—weeks which the Russians used to scrape together what forces they could and concentrate them opposite Reinhardt's bridegheads on the Luga. A workers' division appeared on the front. Two further divisions, the lllth and units of the 125th Rifle Divisions, were brought up by rail. The trains moved unconcernedly within sight of the German troops and unloaded the reinforcements along the track. Finally several armoured formations appeared on the scene with heavy KV-ls and KV-2s.

Some of these brand-new super tanks were still manned by their civilian test crews from the factories. Among the infantry in their wake was an entire works brigade of women— students of Leningrad University. Women were also found dead or wounded inside shot-up tanks.

Other books

Hot Mess by Lynn Raye Harris

Man with the Dark Beard by Annie Haynes

Dangerous Inheritance by Dennis Wheatley

Rosshalde by Hermann Hesse

The Temptress by C. J. Fallowfield, Karen J, Book Cover By Design

If You Ever Tell by Carlene Thompson

Taste of Passion by Jones, Renae

Dragon Wife by Diana Green

Passion Awakened by Jessica Lee