Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (70 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

"Volkhov," the whisper ran through all the unit offices. Volkhov. The men looked it up on their maps. "Some 125 miles to the south of us. And in this weather," they grumbled.

Preparations were complete by 15th March. About 15th March, in Western and Central Europe, people began to think of the spring. But on the Volkhov the temperature was still 50 degrees below zero. The snow lay four feet deep in the thick forests.

The Russians knew what was at stake at their penetration point, and had therefore strengthened it as much as possible. Along the stretch of road controlled by them flame-throwers had been installed and thick minefields laid across all negotiable clearings.

The 220th Infantry Regiment charged the Soviet barriers with its captured enemy tanks and its sapper assault detachments. Fighter-bombers and Stukas of I Air Corps dropped their bombs on Soviet positions and strongpoints. But the deep snow cushioned the bombbursts, and the blast effect was slight. The Russians held their block, and 220th

Infantry Regiment did not get through.

Things went better two miles farther west. There the battalions of 209th Infantry Regiment fought their way forward step by step through the clearings of an almost impenetrable snow-bound forest. The 154th Infantry Regiment likewise struggled through the undergrowth, with self-propelled guns and sappers clearing a path for them. Savage small-scale righting raged throughout the forest.

Time and again the mortars failed in the severe cold: ice kept forming inside the barrels so that the bombs no longer fitted. The gunners had shells bursting inside their barrels because the rifling kept icing up. Machine-guns packed up because the oil got stiff and sticky. The most reliable weapons were hand-grenades, trenching-tools, and bayonets.

Towards 1645 hours on 19th March the most forward units of 2nd Battalion, 209th Infantry Regiment, under Major Materne made their way across the clearing marked on their maps with "E"—known to them as clearing Erika. It is a name well remembered by every one who fought on the Volkhov. It marks a patch of dismal, hotly contested forest. Along the wooden road constructed across this clearing and serving as a supply route a trooper had erected a noticeboard with the words "Here begins the arse-hole of the world." For many months it remained in the same spot where, on that 19th March, the spearheads of Materne's battalion were lurking.

A machine-gun was stuttering from the far end of the clearing. "That's a German m.-g.," one of the men said. "Better be careful, boys," warned Major Materne.

A white flare soared up on the far side. "Answer itl" Materne commanded.

A white fiery ball, like a miniature sun, hissed over the clearing. At the far end a figure wrapped up to the tip of his nose and wearing a German steel helmet emerged from behind a bush, and waved. "Ours!" The men were beside themselves with joy.

Through the snow they raced towards each other, slapped each other's backs, fished out cigarettes, and pushed them between each other's lips. "What do you know," they said to their pals from the forward assault detachments of the SS Police Division. "What do you know—we made it!"

They had made it. The breach was sealed. They had linked up at the clearing Erika, and they had cut the supply route of the Soviet Second Striking Army.

Two Soviet Armies were in the bag. As at Rzhev and at Sukhinichi, the unshakable resistance offered by individual units had created the prerequisites for retrieving a seemingly hopeless situation by means of bold counter-blows and for snatching the initiative from the Russian Armies, grown overconfident and careless through a taste of victory. Once more the hunters became the hunted and the pursued became the pursuers.

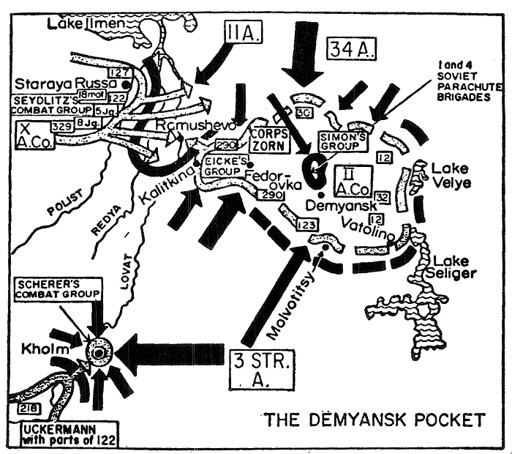

Thus the Soviet assault against the Volkhov was halted and their attempt to relieve Leningrad foiled. But what was happening in the meantime on the strip of land between Lakes Ilmen and Seliger, where five Soviet Armies had boken through and torn a wide gap in the front between Army Group Centre and Army Group North?

On this strip of land only two German barriers were left to stem the Soviet flood—Demyansk and Kholm—and everything now depended on them. If these two strongpoints were over-run or swept away the Soviet Armies would have a clear road into the deep, virtually undefended hinterland of the German front. In the Demyansk area there were six German divisions barring the way to the Russians. Other formations—such as units of 290th Infantry Division, which had held their ground when the Russians broke through at Lake Ilmen and had subsequently been unable to withdraw from their partial encirclement towards Staraya Russa—later broke through in a south-easterly direction to reach II Corps and thus reinforced the defenders of the Demyansk pocket. The II Army Corps under General Count Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt drew the bulk of the Soviet attacking forces of five Armies and tied them down. The Soviet Third Striking Army, advancing farther south, was likewise unable to make any progress in the face of the second immovable barrier across the otherwise empty gap between Demyansk and Velikiye Luki, a barrier blocking the road into the rear of Sixteenth Army—Kholm.

Map 23.

The German divisions at Demyansk and Kholm, acting as breakwaters against the Soviet flood, succeeded in halting three Soviet Armies. The heavy fighting continued until the spring of 1942, when the two German pockets were liberated.

Demyansk and Kholm became crucial for the turn of the tide on the northern wing of the German Armies in the East. The defenders of Demyansk and Kholm wrested the victory from the Soviets by sheer stubborn resistance.

The history of the battle of the Demyansk pocket—a battle lasting twelve and a half months and hence ranking as the longest battle of encirclement on the Eastern Front—began on 8th February 1942. Count Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt, the general commanding II Army Corps, was on the telephone to Sixteenth Army. "We'll try to keep communications open with you at all costs," Colonel-General Busch was saying.

At that moment there was a click in the receiver. The two generals heard the cool voice of the operator at the Corps exchange cut in: "I'm disconnecting now: the enemy's in the line."

The general replaced the receiver. He looked at his ADC and said, "That was probably the last talk we've had with Army for some time to come."

"That means the ring is closed?" the ADC asked.

"Yes," replied the general. After a short pause he added, "At least we know where we are. We'll just have to wait and see."

"Waiting and seeing" turned out to be twelve months and eighteen days of ferocious fighting. The Corps was encircled in an area of 1200 square miles.

The reasons why this battle had to be fought, why a pocket in the middle of the Valday Hills around the dismal dump of Demyansk had to be held against the Soviet assault, were explained by the general in an unusual Order of the Day. Unusual because it not only ordered the officers and men to do a certain thing, but also explained the circumstances and reasons for the order.

On 20th February, therefore, twelve days after they had first been encircled, Count Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt had the following order read to all his formations in the pocket:

"Taking advantage of the coldest winter months, the enemy has crossed the ice of Lake Ilmen, the normally marshy delta of the Lovat river, and the shallow valleys of the Pola, Redya, and Polist, as well as numerous lesser watercourses, and placed himself behind II Corps and its rearward communications. These river-valleys form part of an extensive area of swampy lowlands which get flooded and entirely impassable, even on foot, the moment the ice and snow begin to melt. Any enemy transport, especially the bringing up of supplies on any scale, will then be entirely impossible.

"Russian supplies during the wet spring-time would be possible only along the major hard roads. The intersections of these roads, however—Kholm, Staraya Russa and Demyansk—are firmly in German hands. Moreover, the Corps with its battle-tried six divisions commands the only real piece of high ground in the area. It is therefore impossible for the Russians with their numerous troops to hold out in the wet lowlands without supplies in spring.

"What matters, therefore, is to hold these road junctions and the high ground around Demyansk until the spring thaw. Sooner or later the Russians will have to give in and abandon that ground, especially as strong German forces will be attacking them from the west."

The officers and men listened and nodded. They understood. They were determined to hold "the county," as they called their pocket in an allusion to their general's title.

The battle began. It was the first major battle of encirclement in which the German troops were the encircled. For the first time in military history an entire Corps of six divisions with roughly 100,000 men—virtually a whole Army — was successfully supplied by air. It was on the Valday Hills in Russia that the first airlift in military history went into operation.

Some 500 transport aircraft supplied the 100,000 men of II Corps with everything they needed for survival and fighting—day in, day out. The machines flew regardless of blizzards and frosts, of fog or winter thunderstorms, and regardless of the furious anti-aircraft fire of the Soviets.

About 100 aircraft had to make the flight into the pocket and back each day. On certain days there were as many as

150. This meant that during every hour of the short winter days 10 to 15 aircraft had to land and take off from the two makeshift airstrips.

The feats of these transport units under Colonel Morzik, the Chief of Air Transport, were unparalleled at the time. The scope of the operation is illustrated by two figures: 64,844 tons of cargo were flown into the pocket and 35,400 men— wounded or transferred—were flown out.

The airlift was a decisive contribution to success. But it also mortgaged future German strategy: the German transport squadrons were decimated. Many pilots were killed.

More disastrous still was the fact that the success at Demyansk confirmed Hitler in his decision, nine months later, to

hang on to Stalingrad, because he believed he would be similarly able to keep the encircled Sixth Army with its approximately 300,000 men supplied from the air.

Major Ivan Yevstifeyev, born in 1907, commanded the famous 57th Brigade, the spearhead of the Soviet Second Striking Army, on the Volkhov. He was an outstanding officer, courageous, a skilful leader in the field, and with the full background of a Soviet General Staff training.

When he was taken prisoner he remarked, "It was bound to happen like this, with so much stupidity in our Supreme Command." The report which he wrote shows that the news of the Second Striking Army being pinched off at the bottleneck of the clearing Erika had had a disastrous effect in Moscow. It meant the shattering of Stalin's hopes of liberating Leningrad and annihilating the German Army Group North. Stalin was looking for a scapegoat.

And just as he had dismissed General Sokolovskiy, the Army Commander-in-Chief, during the first week of January for attacking on a broad front and not breaking through, so General Klykov and his Chief of Staff were now sacked because they broke through on too narrow a front. But who was to save the situation now? Who could blow out the bung from the bottleneck and free the bulk of the two Armies encircled in the huge pocket?

Stalin's choice turned out to be a man who was then one of the stars of the Soviet Generals' Corps—Andrey Andrey- evich Vlasov. In the late summer of 1941 Vlasov had courageously defended Kiev for two months, and subsequently, as Commander-in-Chief Twentieth Army, thrown back the northern wing of the German offensive against Moscow at Solnechnogorsk and Volokolamsk. He had been rewarded with orders, praise, fame, and the position of a deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Army Group Volkhov. Now he was to go into action again to prove his generalship.

Vlasov was the son of a small peasant, born in 1901. At considerable sacrifice his father sent him to a priests' seminary. Lenin's revolution decided him to become a Communist, to join the Red Army, to become a regular officer and eventually a general. Owing to the fact that during the thirties he was in China as Chiang Kai-shek's military adviser, he escaped the great purges which claimed Marshal Tukhachevskiy and most of his friends as victims. When Vlasov eventually returned to Russia there was no limit to his career. Very soon his fame as an organizer was proclaimed throughout the Soviet military Press.

Other books

Scattering Like Light by S.C. Ransom

A Christmas Prayer: An Autistic Child, a Father's Love, a Woman's Heart (Christmas Romance) by Rondeau, Linda Wood

The Equinox by K.K. Allen

One night in Daytona (One Night Stands #1) by Ann Grech

The Midwife's Revolt by Jodi Daynard

Cursed by Chemistry by Kacey Mark

Find the Innocent by Roy Vickers

Captain Bjorn (Tales from The Compass Book 1) by Anyta Sunday, Dru Wellington