Mark Griffin (12 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

IT WAS COMPOSER VERNON DUKE who suggested that Minnelli next direct a musical version of the S. N. Behrman play

Serena Blandish

. Minnelli liked the idea but took it a step further—a musical version of

Serena Blandish

—but with an all-black cast. He envisioned Cotton Club headliner Lena Horne in the title role of a young woman being groomed to meet high society. And if Minnelli had his way, Ethel Waters would strut her stuff as the irrepressible Countess Flor Di Folio.

Serena Blandish

. Minnelli liked the idea but took it a step further—a musical version of

Serena Blandish

—but with an all-black cast. He envisioned Cotton Club headliner Lena Horne in the title role of a young woman being groomed to meet high society. And if Minnelli had his way, Ethel Waters would strut her stuff as the irrepressible Countess Flor Di Folio.

In April 1938, it was announced that S. J. Perelman would be tackling the adaptation, and the incomparable Cole Porter was set to compose the score. It seemed that

Serena

had all the makings of another Minnelli-designed blockbuster. But then, as quickly as the project came together, it began to unravel. In September, the

New York Times

broke the news: “Not that anyone ever took it too seriously, but Vincente Minnelli has dropped his plan to present a Negro version of

Serena Blandish

, leaving Mr. M. to consider other ventures.”

6

Serena

had all the makings of another Minnelli-designed blockbuster. But then, as quickly as the project came together, it began to unravel. In September, the

New York Times

broke the news: “Not that anyone ever took it too seriously, but Vincente Minnelli has dropped his plan to present a Negro version of

Serena Blandish

, leaving Mr. M. to consider other ventures.”

6

Mr. M. had also been toying with the idea of mounting “a surrealistic fantasy set to jig time.” Tentatively entitled

The Light Fantastic

, the new show was being planned as a third collaboration for Minnelli and Bea Lillie. Vincente also hoped that for this outing, his friend Dorothy Parker would contribute a sketch or two. All of this was put aside, however, when legendary impresario Max Gordon offered Minnelli an opportunity to design a new musical. With a score supplied by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II (the same team that had revolutionized Broadway a dozen years earlier with

Show Boat

), there were great expectations for the new production,

Very Warm for May

.

s

The Light Fantastic

, the new show was being planned as a third collaboration for Minnelli and Bea Lillie. Vincente also hoped that for this outing, his friend Dorothy Parker would contribute a sketch or two. All of this was put aside, however, when legendary impresario Max Gordon offered Minnelli an opportunity to design a new musical. With a score supplied by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II (the same team that had revolutionized Broadway a dozen years earlier with

Show Boat

), there were great expectations for the new production,

Very Warm for May

.

s

Advance publicity promised that the musical would be “reminiscent of the song and dance fun-fests that used to tenant The Princess Theatre.” The story, which concerned young performers in a summer stock theater getting mixed up with gangsters, was infused with the kind of “let’s put on a show!” exuberance that would soon become a trademark of the Mickey Rooney- Judy Garland musicals of the ’40s. Needless to say, this was material that a fugitive from the Minnelli Brothers Mighty Dramatic Company Under Canvas could relate to completely.

Hammerstein would direct the book, and Minnelli would stage the musical numbers. The cast included future stars Eve Arden, June Allyson, and

Vera-Ellen. In the role of “Smoothy Watson,” a handsome young dancer named Don Loper was cast. He would become one of Vincente’s closest friends and a fixture in the Freed Unit at MGM. “Don Loper’s big claim to fame was that he danced with Ginger Rogers in

Lady in the Dark

,” remembers Tucker Fleming. “In later years, he became quite a designer and he had a big house in Bel Air and he used to entertain a lot—straight parties and gay parties. Even at the gay parties everybody had to wear black tie. He was very pretentious. Wore patent leather shoes. . . . He was very social and the type of guy that would have appealed to Vincente.”

Vera-Ellen. In the role of “Smoothy Watson,” a handsome young dancer named Don Loper was cast. He would become one of Vincente’s closest friends and a fixture in the Freed Unit at MGM. “Don Loper’s big claim to fame was that he danced with Ginger Rogers in

Lady in the Dark

,” remembers Tucker Fleming. “In later years, he became quite a designer and he had a big house in Bel Air and he used to entertain a lot—straight parties and gay parties. Even at the gay parties everybody had to wear black tie. He was very pretentious. Wore patent leather shoes. . . . He was very social and the type of guy that would have appealed to Vincente.”

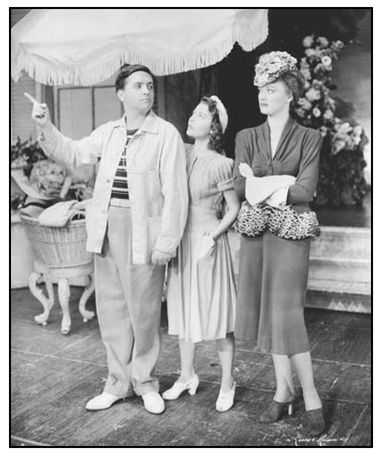

Hiram Sherman, Grace MacDonald, and Eve Arden in

Very Warm for May

. Minnelli would write off the 1939 Broadway musical as “my first disaster.” In later years, Arden would refer to the show as “Very Cold for October.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Very Warm for May

. Minnelli would write off the 1939 Broadway musical as “my first disaster.” In later years, Arden would refer to the show as “Very Cold for October.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Very Warm for May

premiered at The Playhouse in Wilmington, Delaware, in October 1939. The local press was encouraging, and the audience response was equally enthusiastic. The gorgeous ballad “All the Things You Are” seemed destined for the Hit Parade. It looked as though Minnelli had another hit on his hands. Then, producer Max Gordon arrived on the scene and decided it was time to

produce

.

premiered at The Playhouse in Wilmington, Delaware, in October 1939. The local press was encouraging, and the audience response was equally enthusiastic. The gorgeous ballad “All the Things You Are” seemed destined for the Hit Parade. It looked as though Minnelli had another hit on his hands. Then, producer Max Gordon arrived on the scene and decided it was time to

produce

.

Minnelli and choreographer Harry Losee were informed that their services were no longer required. Hassard Short (who had worked on some of Cole Porter’s musicals) and Albertina Rasch were called in to restage scenes and revise the choreography. Gordon began pressuring Hammerstein to drop the show’s gangster subplot. Although he initially resisted Gordon’s “suggestion,” Hammerstein eventually gave in. When

Very Warm for May

opened at the Alvin Theatre on November 17, 1939, it was a very different musical from the one audiences in Wilmington had enjoyed. Remarkably, even with a sizable

chunk of its story missing, the show was well received. “Strangely enough, on opening night we were greeted with laughter, applause, and even bravos,” remembered Eve Arden, queen of the wisecrackers. “Max Gordon, our producer, was ecstatic. I had a chilling feeling that he was being premature, knowing the unpredictability of critics, and I was right.”

7

Very Warm for May

opened at the Alvin Theatre on November 17, 1939, it was a very different musical from the one audiences in Wilmington had enjoyed. Remarkably, even with a sizable

chunk of its story missing, the show was well received. “Strangely enough, on opening night we were greeted with laughter, applause, and even bravos,” remembered Eve Arden, queen of the wisecrackers. “Max Gordon, our producer, was ecstatic. I had a chilling feeling that he was being premature, knowing the unpredictability of critics, and I was right.”

7

Out of respect for Kern and Hammerstein’s previous achievements, the critics stopped short of savaging the show—though just barely. Although Max Gordon had expected an extended run to rival the 289 performances that Rodgers and Hart’s

Babes in Arms

had racked up a year earlier, the Alvin’s box office remained unnervingly quiet. After a dismal 59 performances, the curtain came down on what Minnelli would dismiss as “my first disaster” and Arden would come to refer to as “Very Cold for October.” Only one element of

Very Warm for May

had a life beyond its final curtain call. The winsome “All the Things You Are” would be recorded by a host of popular singers, from Sinatra to Streisand.

Babes in Arms

had racked up a year earlier, the Alvin’s box office remained unnervingly quiet. After a dismal 59 performances, the curtain came down on what Minnelli would dismiss as “my first disaster” and Arden would come to refer to as “Very Cold for October.” Only one element of

Very Warm for May

had a life beyond its final curtain call. The winsome “All the Things You Are” would be recorded by a host of popular singers, from Sinatra to Streisand.

Just up the street from the funeral atmosphere at the Alvin, the Booth Theatre was staging an original play entitled

The Time of Your Life

, which had opened to rapturous reviews. Heralded as “a prose poem in ragtime,” the drama had been written by William Saroyan—a bearish, hugely talented, and more than slightly eccentric true original. Unlikely as it seems, after Saroyan and Minnelli were introduced, they became buddies, though Saroyan biographer John Leggett believes that the playwright may have harbored some ulterior motives in befriending Vincente. “Saroyan was always imagining that by getting to know some influential person, that he would advance his career,” Leggett says. “Minnelli would have appealed to him simply because of his Broadway stature.”

8

The Time of Your Life

, which had opened to rapturous reviews. Heralded as “a prose poem in ragtime,” the drama had been written by William Saroyan—a bearish, hugely talented, and more than slightly eccentric true original. Unlikely as it seems, after Saroyan and Minnelli were introduced, they became buddies, though Saroyan biographer John Leggett believes that the playwright may have harbored some ulterior motives in befriending Vincente. “Saroyan was always imagining that by getting to know some influential person, that he would advance his career,” Leggett says. “Minnelli would have appealed to him simply because of his Broadway stature.”

8

To Minnelli, Saroyan seemed a good choice as the book writer for a proposed all-black revue with no less than Rodgers and Hart furnishing the score. Minnelli and producer Bela Blau commissioned Saroyan to write the script, paying him $200 to begin the project, which was in some ways

Serena Blandish

revisited. “[Saroyan and Minnelli] took the subway to Harlem,” says Leggett. “They went to the Apollo Theatre and they were impressed by seeing the black male dancers there and out on the street. It pleased Saroyan’s imagination but I don’t think they every really got anywhere with that project.”

t

Serena Blandish

revisited. “[Saroyan and Minnelli] took the subway to Harlem,” says Leggett. “They went to the Apollo Theatre and they were impressed by seeing the black male dancers there and out on the street. It pleased Saroyan’s imagination but I don’t think they every really got anywhere with that project.”

t

At one point, Yip Harburg replaced Rodgers and Hart as the revue’s composer. Saroyan continued to churn out sketches at an incredible rate, amazing Minnelli with his swiftness. Despite the remarkable talents involved, the all-black revue never materialized. Even so, memories of his visit to the Apollo and the lindy-hoppers dancing in the streets would remain in Minnelli’s mind when it came time to direct his first film.

IT WAS ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT introductions in the history of Hollywood: Arthur Freed meets Vincente Minnelli. In terms of movie musicals, it was almost as noteworthy as the day Fred met Ginger, though, in later years, nobody could recall the details of the meeting. Did Yip Harburg make the introductions, or was it Roger Edens? Minnelli remembered it happening in the spring of 1939, while others believed that the two first met during the run of

Very Warm for May

. Whatever the circumstances, the point was that Arthur Freed had come calling and Vincente knew that this could be opportunity knocking.

Very Warm for May

. Whatever the circumstances, the point was that Arthur Freed had come calling and Vincente knew that this could be opportunity knocking.

A native-born South Carolinian, Freed had tirelessly scaled the show-business heights, first as a Tin Pan Alley tunesmith. In collaboration with composer Nacio Herb Brown, Freed would make his mark supplying lyrics for such sublime standards as “You Were Meant for Me,” “Good Morning,” “The Wedding of the Painted Doll,” and one of the most enduring and instantly recognizable tunes in the history of popular music, the unforgettable “Singin’ in the Rain.”

Just as the movies were beginning to talk, Freed found himself at MGM, and his songs graced the soundtrack of 1929’s Best Picture Academy Award winner

, The Broadway Melody

. A decade later, Freed served as the uncredited associate producer on

The Wizard of Oz

, one of the finest films (musical or otherwise) to come out of Hollywood and the movie that made Judy Garland, “the little girl with the great big voice,” a major star.

, The Broadway Melody

. A decade later, Freed served as the uncredited associate producer on

The Wizard of Oz

, one of the finest films (musical or otherwise) to come out of Hollywood and the movie that made Judy Garland, “the little girl with the great big voice,” a major star.

“Yep,” “Nope,” and “Terrific” were considered unusually long-winded responses for Arthur Freed, so he got right to the point: “How would you like to work at Metro, Vincente?” Minnelli was ordinarily as tongue-tied as Freed but his answer came quickly: “I’ve been there.” Vincente explained that his experience at Paramount had soured him on the movies. Freed persisted. “They simply didn’t understand you. Come on out for five or six months, take enough money for your expenses. . . . If you don’t like it at any time you can leave.” Minnelli would be working for Freed but without a title. He’d be devising musical numbers, maybe even directing some. What’s more,

he’d be doing it at the biggest studio in Hollywood. Said Minnelli: “Before I knew it had happened, I had already started.”

9

he’d be doing it at the biggest studio in Hollywood. Said Minnelli: “Before I knew it had happened, I had already started.”

9

Suddenly, Minnelli found himself going Hollywood all over again, but this time there was a significant difference: The movies were ready for Vincente Minnelli. “I was getting a fraction of my salary at Paramount,” he noted with obvious disappointment. But otherwise, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer would prove to be a gold mine for Arthur Freed’s colorful new protégé.

As Minnelli was packing his bags, he received word that his mother had died at the age of sixty-eight in St. Petersburg, Florida. After Mina’s death, Vincente’s elderly father and his brother, Paul, would be cared for by his Aunt Amy. While Vincente would keep up a correspondence with his relatives and he provided for them financially, his new employer would keep him so busy that extended visits were out of the question. Besides, Minnelli had a new family now. It was called the Freed Unit.

MGM’s Dream Team: Minnelli and producer Arthur Freed on the set of

The Clock

, 1945. Director Stanley Donen said of his Metro colleagues, “Arthur Freed thought Vincente Minnelli was remarkable. He gave him anything he asked for. . . . He fought for it and got it.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

The Clock

, 1945. Director Stanley Donen said of his Metro colleagues, “Arthur Freed thought Vincente Minnelli was remarkable. He gave him anything he asked for. . . . He fought for it and got it.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

6

“A Piece of Good Luck”

MINNELLI ARRIVED IN CULVER CITY on April 22, 1940. According to the terms of his contract with the studio, he’d be serving in a “general advisory capacity in connection with the preparation for and production of photoplays which contain musical numbers” as well as “the creation, preparation and direction of musical numbers.”

As he didn’t have a title and wasn’t assigned to a specific picture, Minnelli was encouraged to roam around and observe the inner workings of the massive studio, which churned out fifty-two pictures a year. MGM may have been an assembly line like every other studio in town, and perhaps the most conservative of the majors, but it prided itself on producing gleaming Rolls-Royces, not Fords. If 20th Century Fox featured Alice Faye as

Lillian Russell

, MGM could claim Greta Garbo as

Queen Christina

. Sure, Paramount may have had Gary Cooper, but Metro had “The King,” Clark Gable. Even when an MGM film (say, one produced by Joe Pasternak) wasn’t legitimately top of the line (say,

Song of Russia

), it was always slicked up so that it appeared so. With what seemed to be infinite resources at its disposal, Metro had the ability to conjure up Paris in 1883, Oscar Wilde’s London, the San Francisco earthquake of 1903, or Munchkinland.

Lillian Russell

, MGM could claim Greta Garbo as

Queen Christina

. Sure, Paramount may have had Gary Cooper, but Metro had “The King,” Clark Gable. Even when an MGM film (say, one produced by Joe Pasternak) wasn’t legitimately top of the line (say,

Song of Russia

), it was always slicked up so that it appeared so. With what seemed to be infinite resources at its disposal, Metro had the ability to conjure up Paris in 1883, Oscar Wilde’s London, the San Francisco earthquake of 1903, or Munchkinland.

Other books

The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier

Something Suspicious in Sask by Dayle Gaetz

Promethea by M.M. Abougabal

Dogsong by Gary Paulsen

The Treble Wore Trouble (The Liturgical Mysteries) by Schweizer, Mark

Frenzy (The Frenzy Series Book 1) by Casey L. Bond

Her Dying Breath by Rita Herron

Fuck Valentine's Day by C. M. Stunich

Basher Five-Two by Scott O'Grady

The Jacobs Project: In Search of Pinocchio (SYMBIOSIS) by King, Samuel