Mark Griffin (21 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Now that Vincente was married to one of MGM’s most important assets, the studio would carefully scrutinize any images of him that would be seen by the public. If Minnelli was not exactly the kind of strapping All American Boy that Judy’s legions of fans would have envisioned her blissfully wed to, at least the studio could filter out any questionable examples of Vincente’s “artistic flair.” After all, it was one thing for Minnelli to go full tilt flamboyant with a

Ziegfeld Follies

production number, but altogether another matter for him to appear in public bedecked in a turban as he escorted Judy and their friend Joan Blondell to dinner at Romanoff’s. Vincente and Judy’s friends were happy that the two had formed such a close, supportive bond. And many hoped that mild-mannered Vincente might have a calming influence on his high-spirited wife. But even so, they couldn’t help but wonder . . . What kind of marriage was it exactly?

Ziegfeld Follies

production number, but altogether another matter for him to appear in public bedecked in a turban as he escorted Judy and their friend Joan Blondell to dinner at Romanoff’s. Vincente and Judy’s friends were happy that the two had formed such a close, supportive bond. And many hoped that mild-mannered Vincente might have a calming influence on his high-spirited wife. But even so, they couldn’t help but wonder . . . What kind of marriage was it exactly?

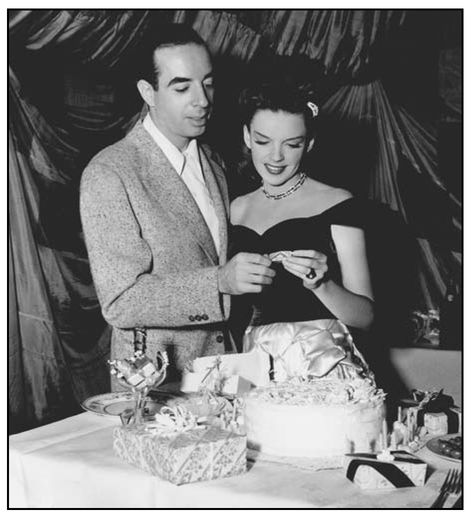

“I admired him before I ever played in one of his pictures,” Garland said of her director-husband. Judy told Hedda Hopper: “He’s one of the hardest working people I’ve ever seen. Players like him. They feel he’s giving his best, so that brings out their best, too.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

The gossip ran the gamut: Garland was attempting to “fix” Minnelli—as in “all he needs is the love of a good woman to make things right.” Or the union was a studio-arranged marriage of convenience that would allow both partners the freedom to pursue extramarital affairs (both heterosexual and homosexual). The more cynically minded observers believed that Minnelli, for all his gentlemanly ways, was a shrewd opportunist hitching his wagon to the studio’s brightest star. But maybe it was the most improbable scenario of all that contained the real truth: Two extravagantly talented, sensitive people turned to one another seeking sanctuary from their intensely pressured lives. What’s more, each could complete the other’s fantasy. “I remember Vincente saying about Judy, ‘She is a great actress and a great star and I will direct her in important parts,’” recalls singer Margaret Whiting, who had befriended Garland years earlier. “I mean, it was obvious that he was interested in her as a director, but I just don’t know what that marriage was all about.”

7

7

In later years, Vincente would describe his New York honeymoon with Judy as a blissful summer idyll complete with heartwarming episodes that might have been deleted sequences from

The Clock

. Three months in Manhattan and away from the confines of Culver City seemed to work wonders

for Garland as she interacted with adoring fans on the street, organized a search for Minnelli’s “neurotic” poodle, experienced live theater, and attempted a new beginning. “Judy gave me a cherished gift—a silent promise,” Vincente remembered. “We were walking in a park by the river. ‘Hold my hand,’ she said softly. I did. It was then that I noticed a vial of pills in her other hand. . . . She threw the pills in the East River. She said she was through with them. But the minute we got back [to Hollywood], anything that would happen at the studio, she would take the pills.”

8

The Clock

. Three months in Manhattan and away from the confines of Culver City seemed to work wonders

for Garland as she interacted with adoring fans on the street, organized a search for Minnelli’s “neurotic” poodle, experienced live theater, and attempted a new beginning. “Judy gave me a cherished gift—a silent promise,” Vincente remembered. “We were walking in a park by the river. ‘Hold my hand,’ she said softly. I did. It was then that I noticed a vial of pills in her other hand. . . . She threw the pills in the East River. She said she was through with them. But the minute we got back [to Hollywood], anything that would happen at the studio, she would take the pills.”

8

IN THE MID-’40S, largely owing to the success of James Cagney’s spirited portrayal of George M. Cohan in

Yankee Doodle Dandy

, all-star musical bio - graphies of America’s top tunesmiths were suddenly hot properties, even if they weren’t entirely factual. Warner Brothers presented Cary Grant as a heterosexual Cole Porter in

Night and Day

, while Metro countered with Mickey Rooney as a heterosexual Lorenz Hart in

Words and Music

. When it came time to dramatize the life of

Show Boat

composer Jerome Kern in

Till the Clouds Roll By

, screenwriter Guy Bolton knew this posed something of a challenge. A confidant of Kern’s, Bolton stood in awe of his friend’s considerable talents, but he also knew that the songwriter’s private life wasn’t remotely cinematic.

Yankee Doodle Dandy

, all-star musical bio - graphies of America’s top tunesmiths were suddenly hot properties, even if they weren’t entirely factual. Warner Brothers presented Cary Grant as a heterosexual Cole Porter in

Night and Day

, while Metro countered with Mickey Rooney as a heterosexual Lorenz Hart in

Words and Music

. When it came time to dramatize the life of

Show Boat

composer Jerome Kern in

Till the Clouds Roll By

, screenwriter Guy Bolton knew this posed something of a challenge. A confidant of Kern’s, Bolton stood in awe of his friend’s considerable talents, but he also knew that the songwriter’s private life wasn’t remotely cinematic.

Though it was true that Kern had cheated death by not sailing on the ill-fated

Lusitania

(his alarm clock didn’t go off), most of the “biography” in the film was pure hokum—including Kern looking after the self-absorbed daughter of a fictional writing partner. To compensate for the lack of dramatic action, the film would be laced with continual references to the theatrical luminaries of the past—a sort of cinematic name-dropping. MGM’s stable of stars would portray some of these fabled legends of yesteryear.

Lusitania

(his alarm clock didn’t go off), most of the “biography” in the film was pure hokum—including Kern looking after the self-absorbed daughter of a fictional writing partner. To compensate for the lack of dramatic action, the film would be laced with continual references to the theatrical luminaries of the past—a sort of cinematic name-dropping. MGM’s stable of stars would portray some of these fabled legends of yesteryear.

The role of Broadway’s Marilyn Miller was reserved for Metro’s even more beloved answer: Judy Garland. While June Allyson, Lena Horne, and Angela Lansbury would have to make do with dance director Robert Alton,

ad

Garland’s sequences were entrusted to Minnelli, now considered Judy’s own personal auteur. Of course, Vincente was well versed in the legend of Marilyn Miller, and he was eager to re-create some of her best-loved numbers—including “Look for the Silver Lining” and “Who?”—on screen. In 1925, Miller had one of her greatest successes with

Sunny

, the saga of a circus bareback rider. The stage show was fondly remembered for its splashy, big-top setting. MGM,

of course, was expected to outdo the original production, and Minnelli’s Technicolored circus made Barnum and Bailey look positively sedate.

ad

Garland’s sequences were entrusted to Minnelli, now considered Judy’s own personal auteur. Of course, Vincente was well versed in the legend of Marilyn Miller, and he was eager to re-create some of her best-loved numbers—including “Look for the Silver Lining” and “Who?”—on screen. In 1925, Miller had one of her greatest successes with

Sunny

, the saga of a circus bareback rider. The stage show was fondly remembered for its splashy, big-top setting. MGM,

of course, was expected to outdo the original production, and Minnelli’s Technicolored circus made Barnum and Bailey look positively sedate.

At one point, the script indicated that during the

Sunny

sequence, Judy was to hurl herself onto the back of a prancing show pony. Obviously, the services of a stunt double would be required, not only because of the risky acrobatic maneuvers involved but also because several months earlier, Judy had discovered that she was pregnant. At age forty-two, Vincente was about to become a father. There was no time to celebrate, as the pressure was on to speed through Garland’s numbers (in a mere two weeks) before the star became too visibly expectant to photograph.

Sunny

sequence, Judy was to hurl herself onto the back of a prancing show pony. Obviously, the services of a stunt double would be required, not only because of the risky acrobatic maneuvers involved but also because several months earlier, Judy had discovered that she was pregnant. At age forty-two, Vincente was about to become a father. There was no time to celebrate, as the pressure was on to speed through Garland’s numbers (in a mere two weeks) before the star became too visibly expectant to photograph.

Originally, the

Sunny

episode was to have included Judy’s rendition of Kern’s winsome “D’Ya Love Me?” Despite Garland’s heartfelt delivery, the number was deleted from the release print of

Clouds

—and it’s a good thing. The surviving footage reveals an oddly uninspired and barely choreographed number. Flanked by a pair of listless clowns, Garland looks uncharacteristically ill at ease. Her comedic grimace when the playback concludes speaks volumes.

Sunny

episode was to have included Judy’s rendition of Kern’s winsome “D’Ya Love Me?” Despite Garland’s heartfelt delivery, the number was deleted from the release print of

Clouds

—and it’s a good thing. The surviving footage reveals an oddly uninspired and barely choreographed number. Flanked by a pair of listless clowns, Garland looks uncharacteristically ill at ease. Her comedic grimace when the playback concludes speaks volumes.

In sharp contrast, the mounting of the buoyant “Who?” was a cinematic bull’s eye. Minnelli encircles Garland, who is gowned in vibrant canary yellow, with a bevy of top-hatted chorus boys in tails. As the star twirls and taps her way through the number, Vincente’s camera keeps pace—an active and fully engaged participant in the proceedings.

Bob Claunch, one of the pompadoured dancers appearing alongside Garland, recalled that working with the frequently tardy star was always worth the wait. “Naturally, I had heard things about her,” Claunch says:

The dancers would talk about their associations with her because they had worked on other films of hers. They knew that she was sick a lot but at that time, nobody really knew what was going on with her. There was a lot of waiting around. I thought to myself at one point, “Where the hell is Judy Garland? She’s supposed to be the star of this. . . .” Finally, Garland came in. And just from seeing [dance instructor] Jeanette Bates do the routine one time, that’s all Judy needed. She did the dance without a rehearsal or anything. We did a master shot. And she left. It was remarkable. I still can’t believe it.

9

9

As expectant parents, both Minnelli and Garland were endlessly amused by the spectacle of a visibly pregnant Judy rushing up to one dashing chorus boy after another and confronting each one with the leading question, “Who?” As Judy and Vincente prepared for the birth of their child, the father-to-be

surely experienced a great complexity of emotions. Only a few years earlier, gossipers on the lot had whispered that Minnelli was “not marrying material,” let alone cut out for fatherhood. In fact, around the studio Judy’s pregnancy had been dubbed “The Immaculate Conception.” Still others in Minnelli’s circle—even those who “knew the score”—believed that Vincente’s quiet demeanor, gentle personality, and fondness for fantasy would make him an excellent father.

surely experienced a great complexity of emotions. Only a few years earlier, gossipers on the lot had whispered that Minnelli was “not marrying material,” let alone cut out for fatherhood. In fact, around the studio Judy’s pregnancy had been dubbed “The Immaculate Conception.” Still others in Minnelli’s circle—even those who “knew the score”—believed that Vincente’s quiet demeanor, gentle personality, and fondness for fantasy would make him an excellent father.

Till the Clouds Roll By

opened in December 1946. The musical would garner much praise for the latest Minnelli-Garland collaboration. Judy’s sequences in the film are imbued with such vitality and presented with such panache that Minnelli’s portion effectively upstages the rest of the movie. In later years, he would helm sequences for other director’s movies (

The Bribe

,

The Seventh Sin

,

All the Fine Young Cannibals

) and usually do so without credit. Nevertheless, a Minnelli moment, whether anonymous or not, had a way of standing out, not only in terms of artful composition but also in the way a scene “felt.”

opened in December 1946. The musical would garner much praise for the latest Minnelli-Garland collaboration. Judy’s sequences in the film are imbued with such vitality and presented with such panache that Minnelli’s portion effectively upstages the rest of the movie. In later years, he would helm sequences for other director’s movies (

The Bribe

,

The Seventh Sin

,

All the Fine Young Cannibals

) and usually do so without credit. Nevertheless, a Minnelli moment, whether anonymous or not, had a way of standing out, not only in terms of artful composition but also in the way a scene “felt.”

Till the Clouds Roll By

would clean up at the box office as almost every MGM musical did in the 1940s. For millions of Americans, going to the movies was a must. The dazzling images of luxurious glamour and double-feature doses of fantasy provided “those wonderful people out there in the dark” with a kind of vital emotional sustenance. You may be broke, knocked up, or limp wristed, but there is always hope for you at the movies. Panty hose may be rationed, but just look at Lucille Bremer decked out in a stunning Sharaff ball gown. At home, the roof is leaking, the rent is late, and nobody understands you. But who cares? Fred Astaire is dancing on the ceiling and Gene Kelly is singing in the rain. An MGM musical was better than a sermon on Sunday for those true believers seeking salvation.

would clean up at the box office as almost every MGM musical did in the 1940s. For millions of Americans, going to the movies was a must. The dazzling images of luxurious glamour and double-feature doses of fantasy provided “those wonderful people out there in the dark” with a kind of vital emotional sustenance. You may be broke, knocked up, or limp wristed, but there is always hope for you at the movies. Panty hose may be rationed, but just look at Lucille Bremer decked out in a stunning Sharaff ball gown. At home, the roof is leaking, the rent is late, and nobody understands you. But who cares? Fred Astaire is dancing on the ceiling and Gene Kelly is singing in the rain. An MGM musical was better than a sermon on Sunday for those true believers seeking salvation.

For Vincente Minnelli, the creation of this kind of rarefied fantasy fulfilled the same psychological and emotional need. While real life had provided the suffocation of a small town, a developmentally disabled brother, and not nearly enough color, the movies—even for the man directing them—possessed the power to transport.

12

Undercurrent

“I’M SURE WE’LL GET ALONG,” Katharine Hepburn announced to Minnelli prior to the start of shooting on

Undercurrent

. According to Vincente, “It sounded like an order and a threat. Never had I met anyone with such self-assurance. She made me nervous. And here was I, theoretically the captain of the ship, being made to tiptoe through my assignment.”

1

Undercurrent

. According to Vincente, “It sounded like an order and a threat. Never had I met anyone with such self-assurance. She made me nervous. And here was I, theoretically the captain of the ship, being made to tiptoe through my assignment.”

1

The assignment was an unusual one for Minnelli—one of those noirish women’s pictures like

Mildred Pierce

,

Nora Prentiss

, or

The Two Mrs. Carrolls

that were in vogue both during and just after the war. Broadway’s Edward Chodorov based his screenplay on a three-part

Woman’s Home Companion

serial by Thelma Strabel entitled

You Were There

. In some ways, both Strabel’s story and Chodorov’s adaptation seemed to be emulating Alfred Hitchcock’s similarly themed but infinitely more satisfying

Suspicion

, in which a terrified Joan Fontaine suspects that suave husband Cary Grant is a murderer.

Mildred Pierce

,

Nora Prentiss

, or

The Two Mrs. Carrolls

that were in vogue both during and just after the war. Broadway’s Edward Chodorov based his screenplay on a three-part

Woman’s Home Companion

serial by Thelma Strabel entitled

You Were There

. In some ways, both Strabel’s story and Chodorov’s adaptation seemed to be emulating Alfred Hitchcock’s similarly themed but infinitely more satisfying

Suspicion

, in which a terrified Joan Fontaine suspects that suave husband Cary Grant is a murderer.

The soft-spoken Fontaine was one thing, but would audiences believe the fiercely independent Hepburn as a damsel in distress? Producer Pandro S. Berman thought so. While at RKO, Berman had shepherded some of Hepburn’s more memorable vehicles (

Sylvia Scarlet

,

Stage Door

) into production. By the 1940s, both the well-respected producer and his star of choice were in residence at MGM. Berman was convinced that the offbeat combination of Hepburn, Minnelli, and a glossy thriller based on Strabel’s novelette would result in a box-office knockout. With Robert Taylor and Robert Mitchum mixed into the batter as Hepburn’s hunky costars, how could

Under current

miss?

Sylvia Scarlet

,

Stage Door

) into production. By the 1940s, both the well-respected producer and his star of choice were in residence at MGM. Berman was convinced that the offbeat combination of Hepburn, Minnelli, and a glossy thriller based on Strabel’s novelette would result in a box-office knockout. With Robert Taylor and Robert Mitchum mixed into the batter as Hepburn’s hunky costars, how could

Under current

miss?

Other books

The Fundamentals of Play by Caitlin Macy

The Glorious Adventures of the Sunshine Queen by Geraldine McCaughrean

Wilder's Mate by Moira Rogers

The Sparrow (The Returned) by Jason Mott

The Winter Bear's Bride (Dubious Book 2) by Mina Carter

The Arcanum by Janet Gleeson

Deciding Love by Janelle Stalder

The Glass Factory by Kenneth Wishnia

The Flame of Wrath by Christene Knight

Touched by Darkness (Young Creator Trilogy) by Christiane Shoenhair