Mark Griffin (26 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

THE MOST ELABORATE Hollywood production that Vincente Minnelli and Judy Garland collaborated on was not

Meet Me in St. Louis

or

The Pirate

but their own marriage. Surely the screen’s brightest star and MGM’s most gifted director would be able to create a life together that was as spectacular and stunning as anything they had produced on the screen.

Meet Me in St. Louis

or

The Pirate

but their own marriage. Surely the screen’s brightest star and MGM’s most gifted director would be able to create a life together that was as spectacular and stunning as anything they had produced on the screen.

Their union may have been completely improbable, but as any screenwriter worth his salt knew, an unlikely love affair sold more tickets than Buck Rogers, Deanna Durbin, and Charlie Chan combined. Judy may have hoped that, as Vincente had helped her to blossom on film, he would aid her off-the-lot

transformation as well. Courtesy of “the Minnelli Touch,” Mayer’s “hunchback” would disappear and a stylish and sophisticated woman of the world would emerge. And with a wedding ring on his finger and a precocious daughter who regularly turned up on his sets, perhaps Vincente was convinced that he would at last silence all the whispers about him. The marriage had been designed to save both of them, but in the end, it proved to be the one MGM production that was missing the studio’s essential component: a happy ending.

transformation as well. Courtesy of “the Minnelli Touch,” Mayer’s “hunchback” would disappear and a stylish and sophisticated woman of the world would emerge. And with a wedding ring on his finger and a precocious daughter who regularly turned up on his sets, perhaps Vincente was convinced that he would at last silence all the whispers about him. The marriage had been designed to save both of them, but in the end, it proved to be the one MGM production that was missing the studio’s essential component: a happy ending.

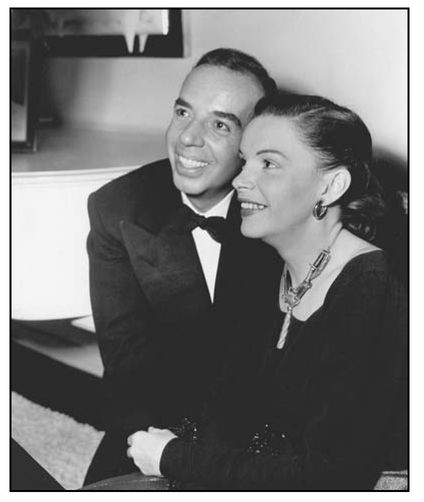

Vincente and Judy in the late 1940s. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

“Looking back on it, I think that marriage was just too much for both of them,” says MGM publicist Esme Chandlee:

Of course, Minnelli was not the strongest figure in the world. Judy was tempestuous. He wasn’t. Though in some ways, you had two personalities that were so completely alike because they were both terribly nervous people. You could always sense the nervousness about Minnelli when you were talking to him. I think maybe Minnelli was “both ways” and that really tolled on him. It was always kind of odd that he got married and had a child to begin with. And with all that was going on with Judy, I don’t think that marriage was the happiest time of his life, either. Though I never heard one of them ever say a bad word about the other. Ever. I think they respected one another—both professionally and as people—but eventually, they realized that being married to each other just didn’t work.

8

8

Given his introverted nature and a need to frequently escape into his own inner world, Minnelli found himself overwhelmed by the torrent of emotion and expectation that his wife sent flowing in his direction every day. Despite Judy’s incomparable talents and widespread acclaim, Minnelli would recall that “her desire for constant approval was pathological.”

9

How could Vincente ever provide all of the validation and reassurance Judy required? At times, it seemed as though Minnelli was tasked with undoing the years of psychological and emotional damage that had been done to Garland—by her mother, Mayer, the studio, and the vagaries of a life lived in the glare of the spotlight. No matter how much tenderness, support, and understanding Vincente could have offered, it would never be enough.

9

How could Vincente ever provide all of the validation and reassurance Judy required? At times, it seemed as though Minnelli was tasked with undoing the years of psychological and emotional damage that had been done to Garland—by her mother, Mayer, the studio, and the vagaries of a life lived in the glare of the spotlight. No matter how much tenderness, support, and understanding Vincente could have offered, it would never be enough.

Eventually, both husband and wife were harboring deep-seated resentments. To Minnelli, the fact that Garland lied to her psychiatrists (according to Vincente, she had seen as many as sixteen) was unforgivable. “Our relationship was drastically damaged,” he recalled.

10

To Judy, the fact that Vincente seemed to side with the studio during her battles with Metro’s front office offered damning evidence that Minnelli wasn’t really married to her but to his own career.

10

To Judy, the fact that Vincente seemed to side with the studio during her battles with Metro’s front office offered damning evidence that Minnelli wasn’t really married to her but to his own career.

16

The Time in His Mind

IT STARTED WITH A TITLE. “Ira, I’ve always wanted to make a picture about Paris,” Arthur Freed said to Ira Gershwin one night in November 1949 after a pool game. “How about selling me the title

An American in Paris

?” Ira agreed, but only if the picture attached to the title contained exclusively Gershwin music. “I wouldn’t use anything else, that’s the object,” was Freed’s response.

1

At that point, the producer wasn’t certain whether his next musical would star Fred Astaire or Gene Kelly, but one thing was certain—with wall-to-wall Gershwin music, this latest Freed Unit endeavor was virtually a guaranteed success even if Bela Lugosi ended up belting “I’ve Got Rhythm.”

An American in Paris

?” Ira agreed, but only if the picture attached to the title contained exclusively Gershwin music. “I wouldn’t use anything else, that’s the object,” was Freed’s response.

1

At that point, the producer wasn’t certain whether his next musical would star Fred Astaire or Gene Kelly, but one thing was certain—with wall-to-wall Gershwin music, this latest Freed Unit endeavor was virtually a guaranteed success even if Bela Lugosi ended up belting “I’ve Got Rhythm.”

In terms of the score, the Gershwin songbook offered an embarrassment of riches. “During early meetings on the project with Arthur, Vincente, Gene and Alan [Jay Lerner] around the piano at my house, somewhere between 125 and 150 songs were played and studied as possibilities,” Ira Gershwin remembered.

2

Among those tunes that would make the final cut were such standards as “’S Wonderful,” “Love Is Here to Stay,” and the rollicking “By Strauss,” which Vincente had introduced in

The Show Is On

.

2

Among those tunes that would make the final cut were such standards as “’S Wonderful,” “Love Is Here to Stay,” and the rollicking “By Strauss,” which Vincente had introduced in

The Show Is On

.

The story, however, didn’t come as easily. Ira Gershwin was reportedly disappointed with

Rhapsody in Blue

, the highly fictionalized, song-studded biopic of 1945 featuring Robert Alda as an ersatz George Gershwin. Taking a lesson from this well-intentioned Warner Brothers extravaganza, Freed decided that

An American in Paris

should not attempt another version of the George Gershwin saga set to the composer’s own work. An original story that somehow referred to the title was required.

Rhapsody in Blue

, the highly fictionalized, song-studded biopic of 1945 featuring Robert Alda as an ersatz George Gershwin. Taking a lesson from this well-intentioned Warner Brothers extravaganza, Freed decided that

An American in Paris

should not attempt another version of the George Gershwin saga set to the composer’s own work. An original story that somehow referred to the title was required.

Both Freed and Kelly would later claim credit for discovering a

Life

magazine article about artists on the G.I. Bill of Rights who stayed on in Paris to paint after the war. The expatriate concept also melded nicely with the fact that in the 1920s, George Gershwin had studied art in Paris—his years there inspiring his immortal tone poem

An American in Paris

, which he described as “a rhapsodic ballet.” Gershwin musical plus the art world could only equal Minnelli, and in February 1950, MGM officially announced that Vincente would helm the production, which would star Gene Kelly, whose presence would be felt in practically every facet of the film’s development.

Life

magazine article about artists on the G.I. Bill of Rights who stayed on in Paris to paint after the war. The expatriate concept also melded nicely with the fact that in the 1920s, George Gershwin had studied art in Paris—his years there inspiring his immortal tone poem

An American in Paris

, which he described as “a rhapsodic ballet.” Gershwin musical plus the art world could only equal Minnelli, and in February 1950, MGM officially announced that Vincente would helm the production, which would star Gene Kelly, whose presence would be felt in practically every facet of the film’s development.

“I think it was in the late spring of 1949 when Arthur Freed first mentioned

An American in Paris

to me,” Alan Jay Lerner recalled. “It must have been some time in November when I finally got some notion of what I was going to do. And that was

a kept man falls in love with a kept woman

. That was the problem that I started with and tried to develop.”

3

Fresh from penning Metro’s effervescent

Royal Wedding

, Lerner was now tasked with creating his second original screenplay. During a Palm Springs retreat, he hammered out the first forty pages of what critics would later describe as a “wafer-thin story,” which focused on the romantic entanglements of Kelly’s brash American painter Jerry Mulligan.

An American in Paris

to me,” Alan Jay Lerner recalled. “It must have been some time in November when I finally got some notion of what I was going to do. And that was

a kept man falls in love with a kept woman

. That was the problem that I started with and tried to develop.”

3

Fresh from penning Metro’s effervescent

Royal Wedding

, Lerner was now tasked with creating his second original screenplay. During a Palm Springs retreat, he hammered out the first forty pages of what critics would later describe as a “wafer-thin story,” which focused on the romantic entanglements of Kelly’s brash American painter Jerry Mulligan.

Residing on the Left Bank, above the quaint Café Hugette, Mulligan spends his days painting, trading quips with neighbor Adam Cook (the “world’s oldest child prodigy”), and supplying Parisian moppets with American bubble gum. An ex-G.I. from Perth Amboy, New Jersey, Mulligan is torn between his chic benefactress, the mink-lined Milo Roberts, and pixyish Parisienne Lise Bourvier. Initially, he doesn’t realize that Lise is already engaged to his best friend, showman Henri Baurel, who selflessly cared for the orphaned l’enfant throughout the occupation.

With Kelly in place and Gershwin confidant Oscar Levant essentially playing himself in the form of acerbic pianist Adam Cook (“the only Adam in Paris without an Eve”), Minnelli and company next focused on filling the role of the sprightly nineteen-year-old ingenue who immediately captivates Mulligan. Contract players Cyd Charisse, Vera-Ellen, and Marge Champion were all briefly considered, but Freed was adamant that an actual Parisian mademoiselle be cast as the enchanting gamine who is “not really beautiful and yet has great beauty.” After viewing tests of French music-hall headliner Odile Versois and a teenager from the Ballets des Champs-Elyssées who had been featured in Roland Pettit’s

Oedipus and the Sphinx

, it was decided that the younger candidate possessed the freshness and spontaneity that the part demanded. She was eighteen years old, and her name was Leslie Caron.

Oedipus and the Sphinx

, it was decided that the younger candidate possessed the freshness and spontaneity that the part demanded. She was eighteen years old, and her name was Leslie Caron.

“I never thought this was serious,” Caron recalled of the studio’s interest in casting her as the thirty-eight-year-old Kelly’s love interest. “I thought, ‘Oh, well, I won’t say no to doing a test if they really want me to . . .’ and then I promptly forgot it. I didn’t see why I needed to go to Hollywood.” In fact, Caron had never even seen Kelly, her hypothetical leading man, on the silver screen.

Caron was not only a demure newcomer struggling with English as a second language but also a self-described “odd bird.” And one suddenly transplanted to a place as disorienting as Hollywood. Even so, the young actress received virtually no guidance from her tongue-tied director. “Vincente is not somebody who talks to actors very easily,” Caron observed. “In fact, I can’t remember him giving me more than one piece of direction in three films that we made together. . . . He stutters and puckers his lips until you try exactly what he wants, but he’s not going to tell you, he’s incapable of it.” According to Caron, Vincente’s only intelligible bit of direction to her throughout the entire filming of

An American in Paris

was, “Just be yourself, darling.”

4

An American in Paris

was, “Just be yourself, darling.”

4

Yves Montand was initially considered for the role of the dapper cabaret star Henri Baurel, but the actor was disqualified because of what technical adviser Alan A. Antik described as Montand’s “communistic tendencies.” Minnelli and Freed next hoped to persuade sixty-two-year-old Maurice Chevalier to accept the role as Caron’s fiancé. Chevalier passed, as his character didn’t wind up with the girl at the final fade out. Besides, the French crooner was “persona non-grata,” as there had been reports that he had performed for Nazi sympathizers during World War II. Ultimately, the more age-appropriate Georges Guetary won the role and one of the film’s showstoppers, “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise.”

In casting the pivotal role of Milo Roberts, the competition again boiled down to two contenders: Nina Foch and Celeste Holm, the latter having just snared a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination for her role in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s blistering bitchfest

All About Eve

. After hearing Foch read the scene in which Milo tells Mulligan that her family “is in oil—suntan oil,” it became obvious that no further testing was necessary. “It was decided that Nina had just the right amount of

savoir-faire

, worldliness, sweetness and bitchiness,” Gene Kelly would later observe.

5

All About Eve

. After hearing Foch read the scene in which Milo tells Mulligan that her family “is in oil—suntan oil,” it became obvious that no further testing was necessary. “It was decided that Nina had just the right amount of

savoir-faire

, worldliness, sweetness and bitchiness,” Gene Kelly would later observe.

5

“I’d already been a small-time movie star at Columbia,” Nina Foch recalled. “I was under contract and I made one picture after the other.” On the way up, the cool, patrician Foch had endured such low-grade schlock as

The Return of the Vampire

and

Cry of the Werewolf

:

The Return of the Vampire

and

Cry of the Werewolf

:

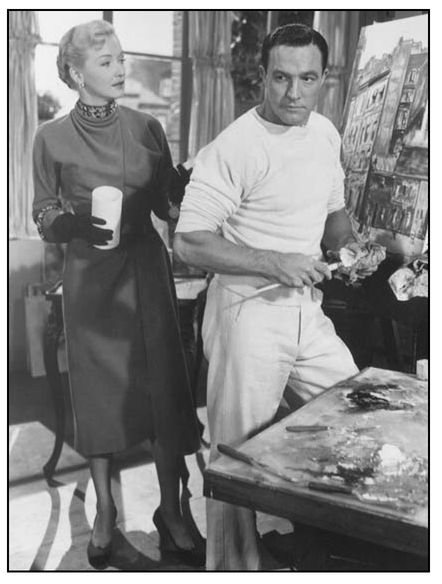

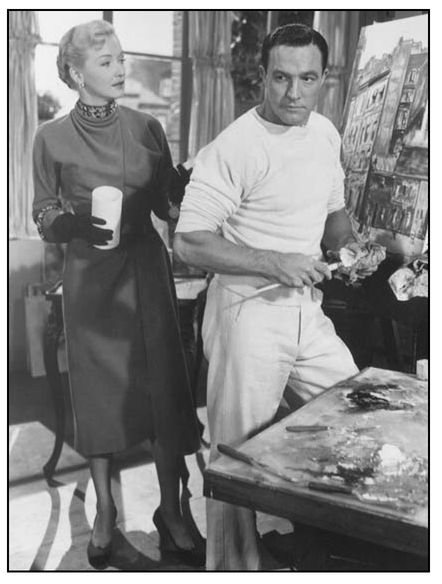

Milo Roberts (Nina Foch) hovers over her handsome, multitalented protégé Jerry Mulligan (Gene Kelly) in

An American in Paris

. According to Foch, some of her best work wound up on the cutting room floor.

An American in Paris

. According to Foch, some of her best work wound up on the cutting room floor.

PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

I hadn’t been happy at Columbia. I didn’t like the people. I didn’t like the movies. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing there. Most of the stuff you do, you do because you’re in the profession. I mean, all of this crap we talk about movies after we’ve made them. . . . Usually we’re trying to figure out something clever to say to the press that’s after you. Half of the time, we’ve made it up and then by the time we’ve said it twenty-seven times, we start to believe it. That’s not true about

An American in Paris

. That was an honor to be in. The Arthur Freed Unit, you know. This was a very classy thing. At the time, I knew I was in something special but I had no clue as to how special.

6

An American in Paris

. That was an honor to be in. The Arthur Freed Unit, you know. This was a very classy thing. At the time, I knew I was in something special but I had no clue as to how special.

6

Other books

Forever and Always by Leigh Greenwood

Dangerous by Sylvia McDaniel

Tangling With Ty by Jill Shalvis

Daniel Ganninger - Icarus Investigations 03 - Snow Cone by Daniel Ganninger

Gemma by Charles Graham

Materia by Iain M. Banks

Summer in Eclipse Bay by Jayne Ann Krentz

Groom in Training by Gail Gaymer Martin

Darkening Chaos: Book Three of The Destroyer Trilogy by Gladden, DelSheree