Mark Griffin (37 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

When the Oscar nominations were announced, Douglas and Quinn found themselves contenders in the Best Actor and Best Supporting Actor categories, respectively. Although Douglas would go home empty handed (though still in character), Quinn copped the Best Supporting Actor prize for his nine-minute turn as Gauguin, prompting rival Mickey Rooney to turn to fellow nominee Robert Stack and lament, “We wuz robbed.”

14

Of course, the real injured party was

Lust for Life

’s director. Despite all of the critical approbation, Minnelli hadn’t even been nominated as Best Director. Once

again, he had been passed over in favor of some dubious contenders. Having an opportunity to pay tribute to one of his idols had proved to be the real reward: “I felt a great affinity for van Gogh. . . . He was too much for anybody. Nobody could live with him for more than a couple of weeks without going mad. Because he gave too much, he wanted too much. And this is the kind of character that is inconsistent and therefore I think brilliant to work out.”

15

14

Of course, the real injured party was

Lust for Life

’s director. Despite all of the critical approbation, Minnelli hadn’t even been nominated as Best Director. Once

again, he had been passed over in favor of some dubious contenders. Having an opportunity to pay tribute to one of his idols had proved to be the real reward: “I felt a great affinity for van Gogh. . . . He was too much for anybody. Nobody could live with him for more than a couple of weeks without going mad. Because he gave too much, he wanted too much. And this is the kind of character that is inconsistent and therefore I think brilliant to work out.”

15

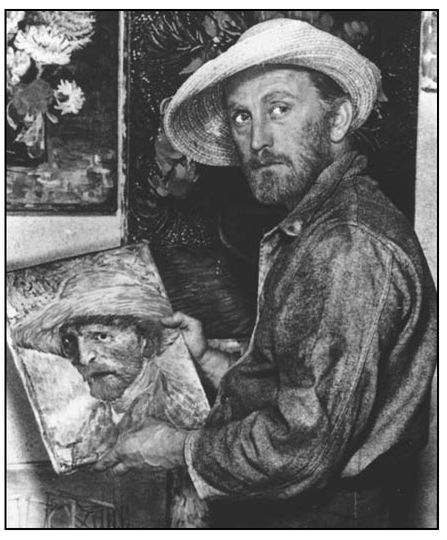

Self-Portrait: Kirk Douglas as van Gogh in

Lust for Life

. “He directs like a madman,” Douglas said of Minnelli. “If you don’t know him, he can drive an actor crazy. But what comes out is beautiful.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Lust for Life

. “He directs like a madman,” Douglas said of Minnelli. “If you don’t know him, he can drive an actor crazy. But what comes out is beautiful.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

23

Sister Boy

“IT HAS NOTHING to do with homosexuality,” Robert Anderson would say of his best-known work,

Tea and Sympathy

. Though others would beg to differ. “

Tea and Sympathy

is definitely about being homosexual,” says film historian Richard Dyer. “It’s about curing homosexuality and the signs of homosexuality are effeminacy.” This echoed the feelings of many who felt that Anderson somehow missed the point of his own story. The author, however, remained insistent: “It’s about a false charge of homosexuality . . . but that is not a gay play.”

1

Tea and Sympathy

. Though others would beg to differ. “

Tea and Sympathy

is definitely about being homosexual,” says film historian Richard Dyer. “It’s about curing homosexuality and the signs of homosexuality are effeminacy.” This echoed the feelings of many who felt that Anderson somehow missed the point of his own story. The author, however, remained insistent: “It’s about a false charge of homosexuality . . . but that is not a gay play.”

1

Tea and Sympathy

, which opened on Broadway in 1953, is set in a prestigious New England prep school. Tom Lee, a sensitive, artistically inclined “off horse,” is assumed to be gay and shunned by his classmates. While the real men on campus are out playing handball or climbing mountains, Tom thinks nothing of getting gussied up in drag to play Lady Teazle in

The School for Scandal

. As if the chintz curtains hanging in his dorm room aren’t bad enough, seventeen-year-old Tom has no interest in becoming a businessman like his father but instead intends to ply his trade as a folk singer who performs “long-hair music.”

, which opened on Broadway in 1953, is set in a prestigious New England prep school. Tom Lee, a sensitive, artistically inclined “off horse,” is assumed to be gay and shunned by his classmates. While the real men on campus are out playing handball or climbing mountains, Tom thinks nothing of getting gussied up in drag to play Lady Teazle in

The School for Scandal

. As if the chintz curtains hanging in his dorm room aren’t bad enough, seventeen-year-old Tom has no interest in becoming a businessman like his father but instead intends to ply his trade as a folk singer who performs “long-hair music.”

The vulnerable outcast is also more comfortable in the company of women, especially Laura Reynolds, the motherly wife of the burly headmaster. Tom harbors a crush on Laura and feels connected to her as a kindred spirit. Observing how Tom is ostracized and tormented by the other students (all “regular fellows”), Laura befriends him, believing that he is a nice, sensitive kid who doesn’t even know the meaning of the word “queer.” Just before the

curtain falls, in a moment of supreme self-sacrifice, Laura offers herself (body and soul) to Tom with the immortal line, “Years from now . . . when you talk about this . . . and you will . . . be kind.”

curtain falls, in a moment of supreme self-sacrifice, Laura offers herself (body and soul) to Tom with the immortal line, “Years from now . . . when you talk about this . . . and you will . . . be kind.”

It was steamy stuff for 1953. Therefore, it came as no surprise to anyone that MGM, which acquired the rights to the play (for a then impressive $150,000), would not have an easy time convincing Production Code administrators Joseph Breen, Geoffrey Shurlock, and Jack Vizzard that its screen version of

Tea and Sympathy

would be sufficiently sanitized to receive the censor’s stamp of approval. From the moment Minnelli and producer Pandro Berman were assigned to the picture, there were countless discussions regarding how such verboten themes could be presented in a mainstream film. As Vincente recalled, “[Berman said] that if the play had actually been about homosexuality, the motion picture code wouldn’t have permitted us to do it.”

2

Robert Anderson, who was adapting his own work, was prepared to make changes to placate the censors. In a creative trade-off, the author was willing to downplay any elements in the script that smacked of “sexual perversion” as long as Tom and Laura’s adulterous affair remained.

Tea and Sympathy

would be sufficiently sanitized to receive the censor’s stamp of approval. From the moment Minnelli and producer Pandro Berman were assigned to the picture, there were countless discussions regarding how such verboten themes could be presented in a mainstream film. As Vincente recalled, “[Berman said] that if the play had actually been about homosexuality, the motion picture code wouldn’t have permitted us to do it.”

2

Robert Anderson, who was adapting his own work, was prepared to make changes to placate the censors. In a creative trade-off, the author was willing to downplay any elements in the script that smacked of “sexual perversion” as long as Tom and Laura’s adulterous affair remained.

The first compromise involved the elimination of a pivotal character in the play. David Harris, “a good-looking young master,” is forced to resign after his students complain to the dean that the instructor and Tom were discovered together, cavorting “bare-assed” in the dunes. Although the David Harris character appears only once, in the first act, his presence is key. Branded “a fairy” by Laura’s husband, Harris is an all-too-real reminder of what the effeminate, impressionable Tom Lee might eventually morph into. Harris is also the physical embodiment of

Tea and Sympathy

’s real villain: homosexuality itself. The gay threat is more palpable in Anderson’s play than in Minnelli’s film. As Deborah Kerr, who starred in both versions, noted, “The crucial point of the play, that [Tom] had been swimming with a master everyone assumed to be homosexual, had to be omitted altogether. The boy was so innocent he would not even have known what that meant—he went with the man because he was nice to him—and that was all there was to it.”

3

Needless to say, Leo the Lion could never roar before a film containing such blatant homoerotic overtones. In life as in the play, Harris would have to go.

Tea and Sympathy

’s real villain: homosexuality itself. The gay threat is more palpable in Anderson’s play than in Minnelli’s film. As Deborah Kerr, who starred in both versions, noted, “The crucial point of the play, that [Tom] had been swimming with a master everyone assumed to be homosexual, had to be omitted altogether. The boy was so innocent he would not even have known what that meant—he went with the man because he was nice to him—and that was all there was to it.”

3

Needless to say, Leo the Lion could never roar before a film containing such blatant homoerotic overtones. In life as in the play, Harris would have to go.

Then there was the matter of Laura’s act of erotic charity. According to the Motion Picture Production Code’s restrictions, the very married den mother could assist the effete protagonist in unleashing his manhood, but she’d have to be punished for it. The Production Code insisted that it be made clear to audiences that although Laura’s mission was a “noble” one,

there would be devastating consequences as a result of her philanthropic infidelity. Anderson was forced to tack on a contrived prologue and epilogue. It was now revealed that the headmaster’s wife was banished from her marriage and the school and was last known to be residing “somewhere near Chicago”—a fate worse than death in the eyes of MGM and the Legion of Decency.

there would be devastating consequences as a result of her philanthropic infidelity. Anderson was forced to tack on a contrived prologue and epilogue. It was now revealed that the headmaster’s wife was banished from her marriage and the school and was last known to be residing “somewhere near Chicago”—a fate worse than death in the eyes of MGM and the Legion of Decency.

Yet another serious Production Code violation involved Tom’s misguided effort to prove his manhood by visiting the town whore, Ellie Martin. “The element of the boy’s attempt to sleep with the prostitute is thoroughly unacceptable as written,” proclaimed Joseph Breen. Clearly any filmmaker intent on bringing

Tea and Sympathy

to the screen had his work cut out for him.

ao

Tea and Sympathy

to the screen had his work cut out for him.

ao

“Persistence has paid off for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in the case of

Tea and Sympathy

,” the

New York Times

reported in September 1955. “The Production Code Administration was prepared to resist its filming. Homosexuality, or rather the suspicion of such that motivates the play, and adultery are proscribed by the Code . . . but Dore Schary, head of the studio, and Pandro S. Berman believed there was a way to resolve the problem.”

4

Although Berman assured the

Times

that Minnelli’s movie would “retain all the essentials” of the play, it was clear that

Tea and Sympathy

could push the envelope—but only so far. Episodes and overt dialogue (“All right, so a woman doesn’t notice these things. But a man knows a queer when he sees one . . .”) that had been acceptable in Elia Kazan’s Broadway production would never pass muster in a feature produced by a major Hollywood studio.

Tea and Sympathy

,” the

New York Times

reported in September 1955. “The Production Code Administration was prepared to resist its filming. Homosexuality, or rather the suspicion of such that motivates the play, and adultery are proscribed by the Code . . . but Dore Schary, head of the studio, and Pandro S. Berman believed there was a way to resolve the problem.”

4

Although Berman assured the

Times

that Minnelli’s movie would “retain all the essentials” of the play, it was clear that

Tea and Sympathy

could push the envelope—but only so far. Episodes and overt dialogue (“All right, so a woman doesn’t notice these things. But a man knows a queer when he sees one . . .”) that had been acceptable in Elia Kazan’s Broadway production would never pass muster in a feature produced by a major Hollywood studio.

Deborah Kerr had won raves on Broadway as Laura Reynolds and she was enthusiastic about recreating her role on film under Minnelli’s direction. The censors had her worried, however, as she revealed in a letter to Vincente: “Adultery is o.k.—impotence is o.k. but perversion is their bête noir!! . . . It

really

is a play about persecution of the individual, and compassion and pity and love of one human being for another in crisis. And as such can stand alone I think—without the added problem of homosexuality. But above all—it needs a sensitive and compassionate person to make it—and that is why I’m so thrilled at the prospect of your doing it.”

5

really

is a play about persecution of the individual, and compassion and pity and love of one human being for another in crisis. And as such can stand alone I think—without the added problem of homosexuality. But above all—it needs a sensitive and compassionate person to make it—and that is why I’m so thrilled at the prospect of your doing it.”

5

Were the words “sensitive” and “compassionate” Kerr’s way of suggesting that there was more than a touch of Vincente Minnelli in Tom Lee? And

what did Minnelli think about directing a story that was so undeniably similar to his own experience that it practically bordered on documentary? The scenes of Tom Lee being bullied and persecuted for his effeminacy must have dredged up some unhappy memories of Delaware and Minnelli’s own years as a playground pariah. Laura giving herself to Tom so that he can prove his manhood and convince himself that he’s unquestionably heterosexual seemed to many Hollywood insiders to be a page right out of the Minnelli-Garland wedding album. What’s more,

Tea and Sympathy

is all about people performing—not in a theatrical milieu but in everyday life. Tom Lee actually rehearses the role of “regular fellow” to avoid being taunted; Laura’s husband, Bill, is playacting his way through a conventional marriage; and even Tom’s brawny roommate, Al Thompson, admits that despite his locker-room swagger, he’s never been alone with a girl. All the world’s a stage, even in a Minnelli melodrama.

what did Minnelli think about directing a story that was so undeniably similar to his own experience that it practically bordered on documentary? The scenes of Tom Lee being bullied and persecuted for his effeminacy must have dredged up some unhappy memories of Delaware and Minnelli’s own years as a playground pariah. Laura giving herself to Tom so that he can prove his manhood and convince himself that he’s unquestionably heterosexual seemed to many Hollywood insiders to be a page right out of the Minnelli-Garland wedding album. What’s more,

Tea and Sympathy

is all about people performing—not in a theatrical milieu but in everyday life. Tom Lee actually rehearses the role of “regular fellow” to avoid being taunted; Laura’s husband, Bill, is playacting his way through a conventional marriage; and even Tom’s brawny roommate, Al Thompson, admits that despite his locker-room swagger, he’s never been alone with a girl. All the world’s a stage, even in a Minnelli melodrama.

There’s no evidence that Vincente ever resisted the project because he felt that Tom Lee’s story hit too close to home. Instead, the most Minnelli would allow—at least publicly—was that “ostrich-wise, the censors refused to admit the problem of sexual identity was a common one.”

6

6

As production began in March 1956, Minnelli may have felt like an outsider on his home turf. Along with Deborah Kerr, several members of the stage production had been retained for the film. During the Broadway run of

Tea and Sympathy

, the actors had not only bonded with one another but with Kazan, whom they revered. John Kerr (who had appeared in Minnelli’s

The Cobweb

) would reprise his role as the hero in touch with his feminine side, and Leif Erickson would again play Bill Reynolds, Tom’s burly housemaster—a character Vincente suggested was “perhaps a latent homosexual himself.”

7

Tea and Sympathy

, the actors had not only bonded with one another but with Kazan, whom they revered. John Kerr (who had appeared in Minnelli’s

The Cobweb

) would reprise his role as the hero in touch with his feminine side, and Leif Erickson would again play Bill Reynolds, Tom’s burly housemaster—a character Vincente suggested was “perhaps a latent homosexual himself.”

7

Broadway’s Dick York was unavailable to reprise his role in the film as Tom’s roommate. Jack Larson, forever identified as Jimmy Olsen of

The Adventures of Superman

series, met with Minnelli to discuss the part. “He had eyes like Bette Davis was supposed to have,” Larson recalls. “I found him effeminate. I guess they would have politely called it

epicene

. He was very courteous to me. He could have been a Noel Coward leading man but he wasn’t handsome at all. There was nothing attractive about him and there was a languor to him. I sat with him in his office, which was very fancy. Everything was in very good taste. . . . There weren’t any little Greek statues around.”

8

Minnelli was impressed with Larson, but at Robert Anderson’s urging the part was ultimately awarded to Darryl Hickman, who years earlier had appeared in

Meet Me in St. Louis

.

The Adventures of Superman

series, met with Minnelli to discuss the part. “He had eyes like Bette Davis was supposed to have,” Larson recalls. “I found him effeminate. I guess they would have politely called it

epicene

. He was very courteous to me. He could have been a Noel Coward leading man but he wasn’t handsome at all. There was nothing attractive about him and there was a languor to him. I sat with him in his office, which was very fancy. Everything was in very good taste. . . . There weren’t any little Greek statues around.”

8

Minnelli was impressed with Larson, but at Robert Anderson’s urging the part was ultimately awarded to Darryl Hickman, who years earlier had appeared in

Meet Me in St. Louis

.

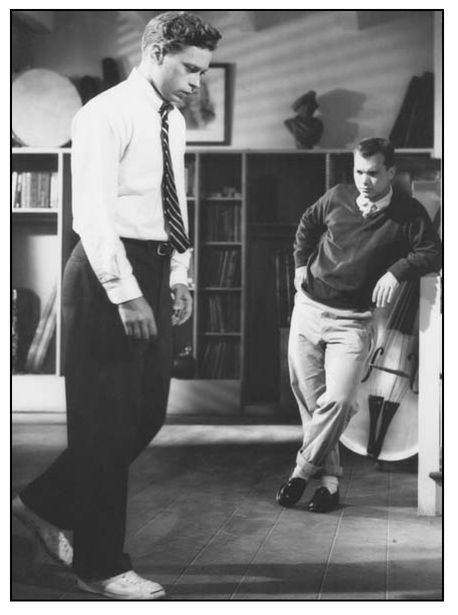

“Minnelli could be so prissy. I mean, he would drive me nuts,” Hickman says. “I remember going in to shoot the ‘walking’ scene with John Kerr, who

never talked to me. I remember standing there from nine o’clock in the morning until noon because we went to lunch without ever having rehearsed the scene.” The infamous “walking” scene, in which Al teaches light-in-his-loafers Tom Lee to walk like a man, was one of the most mind-blowing sequences in the film and later a highlight of the 1995 gay-themed documentary

The Celluloid Closet

.

never talked to me. I remember standing there from nine o’clock in the morning until noon because we went to lunch without ever having rehearsed the scene.” The infamous “walking” scene, in which Al teaches light-in-his-loafers Tom Lee to walk like a man, was one of the most mind-blowing sequences in the film and later a highlight of the 1995 gay-themed documentary

The Celluloid Closet

.

Man Power: Tom Robinson Lee (John Kerr) asks his roommate Al (Darryl Hickman) to help him perfect his manly stride in 1956’s

Tea and Sympathy

. “I don’t think he was that secure about himself,” Hickman says of his director. “I think he made up for whatever lack of self-confidence he may have had as a person in his work. . . . I would say that he had a very important inner world that the films represented.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Tea and Sympathy

. “I don’t think he was that secure about himself,” Hickman says of his director. “I think he made up for whatever lack of self-confidence he may have had as a person in his work. . . . I would say that he had a very important inner world that the films represented.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

According to Hickman, Minnelli obsessed endlessly over the visual details in the scene. Valuable production time was eaten up as Vincente returned to his window-dressing roots with a vengeance. The director arranged various props on the set (including a bust of Beethoven) so that they were

just so

and maneuvered his actors as though they were Marshall Field mannequins. “It looks artificial to me when I watch myself doing it,” Hickman says of his Minnelli-dictated delivery:

just so

and maneuvered his actors as though they were Marshall Field mannequins. “It looks artificial to me when I watch myself doing it,” Hickman says of his Minnelli-dictated delivery:

He had me doing things with my arms, my hands, and with objects, and it was so precise. You know, if you’re a real actor’s director, you don’t do that to

an actor. It makes you very self-conscious. It makes you feel like a robot. And a really good actor’s director like George Cukor would never do something like that to an actor. I don’t think Minnelli, with all of his success and with all of his wonderful work that he did in films, was ever really an actor’s director. First of all, if you’re a really good actor and you have the stature, you say, “Go fuck yourself . . . I’m going to do this the way I want to do it.” I mean, he certainly didn’t tell Deborah Kerr what to do.

9

an actor. It makes you very self-conscious. It makes you feel like a robot. And a really good actor’s director like George Cukor would never do something like that to an actor. I don’t think Minnelli, with all of his success and with all of his wonderful work that he did in films, was ever really an actor’s director. First of all, if you’re a really good actor and you have the stature, you say, “Go fuck yourself . . . I’m going to do this the way I want to do it.” I mean, he certainly didn’t tell Deborah Kerr what to do.

9

Other books

Food Over Medicine by Pamela A. Popper, Glen Merzer

Miss Lacey's Last Fling (A Regency Romance) by Hern, Candice

The Weird Sisters by Eleanor Brown

Broken (Endurance) by Thomas, April

Loving by Danielle Steel

Most Eligible Cowboy (Peach Valley Romance Book 1) by Carly Morgan

A Toast Before Dying by Grace F. Edwards

Quantum Poppers by Matthew Reeve

Goldilocks by Ruth Sanderson

Blood Men by Paul Cleave