Out of Tune (16 page)

Authors: Margaret Helfgott

Claire said recently: “My relationship with all of David’s family was an excellent one. I could see how close they were, which

I liked since I had come from a very close family myself. David had taken me to visit his parents a few times before we were

married. His father always welcomed him by putting his arm around him. After the first time we visited, David was very happy

because, he said, “My mom and dad liked you very much.”

“Peter and Rae often came to visit us. Peter was kind and good-natured. We used to chat about life in Eastern Europe. My children

all liked him very much—he told them jokes and stories from the circus and played the violin for my daughter, who also became

friendly with David’s youngest sister Louise.”

Claire was stunned by what she saw in

Shine

: “During the whole time that I was with him, David never once told me that his father had beaten him or ill-treated him in

any way. He always talked about his father with love. He told me how lonely he had felt in England, and how many times he

had thought to himself that perhaps he should never have left. He told me that it was at those times that he realized how

wrong it would have been if he had gone alone to America after Isaac Stern’s visit.”

There is no sense in which David was “lying dying on the floors of halfway houses” after his return from London, as Scott

Hicks claimed at the official pre-Oscar press conference in Los Angeles. Nor was his life devoid of music until Gillian“rescued”

him. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s David spent a great deal of time at the piano and gave many concerts, especially during

the period when he was under Claire’s solicitous eye.

Allan Macpherson, a former classical music radio producer who knew both David and Claire very well throughout this time, recalls:

“In his first year with Claire, David’s playing and mental condition improved. Claire asked Carl Berent, who had successfully

trained two State winners in the ABC Concerto and Vocal Competition, to train David. David liked Carl and felt comfortable

with him. Carl was fully aware of David’s mental condition and could communicate with him better than anyone else I knew.”

At the time he met Claire, according to Macpherson, David could play long and difficult pieces but lacked finesse. The first

thing Carl persuaded him to do was to slow his playing down, in some cases to half speed, as David tended to race his pieces

and bravura passages. He also transformed David’s somewhat “bashy” sound into a more sophisticated tone. He worked with him

to prepare a recital of solo pieces, improving David’s keyboard technique as well as his conceptual approach to music; and

he inculcated the romance, drama, and tragedy that the pieces required. They worked together on “Pictures at an Exhibition”

by Mussorgsky, the Sonata in B Minor by Liszt, “Gaspard de la Nuit” by Ravel, “Lisle Joyeuse” by Debussy, the “Appassionata”

Sonata by Beethoven, and the Ballade in G Minor and Polonaise in E Minor by Chopin.

Macpherson was intimately involved in classical musical circles in Western Australia at the time and wrote regularly on classical

music for various magazines. “David was quite remarkable to hear,’ he recalls. “He played powerfully and managed difficult

bravura passages with great dexterity and accuracy. He was in excellent physical condition. I remember that he had broad shoulders

and that his back muscles rippled through his shirt when he played. There was no sign of the hunchback or disabled demeanor

he was to develop later.

“He was friendly, even ingratiating, but mostly shy,” Macpherson continues. “His only eccentricities were noisy breathing

and face-pulling while he performed. He kept his face very close to the keyboard and sometimes muttered along with the music

as he played. When I helped him and Carl by turning the pages David spoke little but frequently said ‘yes, Yes, yes.’ David

was different. My first impression of him was that he was an inhabitant of another place, another world. Everyone made a tremendous

fuss of him and I am sure that he enjoyed the attention.”

In 1972, David’s mental condition again took a turn for the worse. He became morose and languid, stopped exercising, and even

gave up playing the piano for several weeks. That year he failed to qualify for the ABC Concerto and Vocal Competition, which

greatly upset him. “Claire tried to do everything for him—she even negotiated with the ABC to enable David to give broadcasts

of piano works, but his playing was so poor and he was so uncommunicative that they abandoned the project,” says Macpherson.

With Carl and Claire’s help, however, David’s playing improved again. In July 1973 he gave a triumphant performance of Shostakovich’s

Concerto for Piano, Trumpet and Strings with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra. Under the heading “Pianist Dazzles at

Concert,” the music critic of

The West Australian newspaper,

Mary Tannock, gave it a glowing report: “Local pianist David Helfgott stole the show at the Perth Concert Hall last night

… Mr Helfgott gave a dazzling display. He brilliantly juxtaposed frenzied clarity in the first movement with even-tempered

expressiveness in the second. The detail and momentum of the entire interpretation was superb.”

But as is often the case with people suffering from schizo-affective disorder, David’s condition gradually grew worse. Living

with him, admits Claire, could be very difficult. Allan Macpherson recalls that “when David reentered the ABC competition

a year later and was not even placed, he cried and muttered so much that Claire had to get the paramedics to help get him

home. Claire’s effort in looking after David was nothing short of superhuman. She cared for David a great deal, and looked

after him continuously without any support from outside agencies. She became a focus of love for him, a kind of whole world,

just like the piano. Claire was only a small woman and David almost engulfed her. He would lock his arms around her shoulders

and continually kiss her on the cheek, stroke her arms, and fondle her clothing. He would behave like this in company, which

I think became embarrassing for Claire. When he was not touching her, he would stare at her transfixed as if experiencing

a religious vision.”

Claire now says that in spite of his condition at that time, David was nevertheless far better then than he is now. “You could

conduct a proper conversation with him and his piano playing was also better. He did not smoke or drink lots of tea or coffee;

and he did not kiss or hug or touch people, including almost total strangers, to the extent he does now.”

In 1974, things continued to decline and David’s behavior grew more erratic. Claire remembers that he would physically cling

to her and when she had to go to give cooking lessons, she always wondered where he would be when she got home. Sometimes,

he would spend hours practicing, but at other times he would run to the beach, a couple of miles away, and swim for hours.

Once she had to fetch the lifeguards to bring him back to shore because he just wouldn’t get out of the water.

One day, after searching everywhere for David, Claire discovered that he had admitted himself to Graylands Psychiatric Hospital.

“He had done so without telling me first. I was extremely upset. I had realized that he would never fully recover, but I thought

that with treatment his illness could be controlled without the need for further hospitalization. I went to see him every

day. Peter and other family members were always there. I sat with him for hours and also often phoned. David told me over

and over again that the pianist Horowitz had been in a mental hospital and had come out healthy and playing again. `It doesn’t

matter if I am a bit different,’ he said, I’ll be okay.’”

Naturally, this was a terrible time for the entire Helfgott family. I visited David frequently. It was very upsetting for

us to see him so heavily medicated and looking so distraught.

When David was allowed to leave the hospital in April 1975, he decided to move back into the family home, explaining to Claire

that his family could devote all their attention to him, whereas she had her own children to care for. Claire said: “As much

as he said he needed me and loved me, he needed the warmth of his parents even more.”

In the meantime, David had fallen in love with another woman, whom he had met in the hospital. Claire and David saw less and

less of each other, and eventually divorced. Claire recalls, “At that time I thought it better to stay away from David as

there was not much more I could do for him under the circumstances.”

Scott Hicks chose to leave Claire out of

Shine

altogether. One reason for this may be that including her would have altered the impression that Gillian was David’s savior,

and that David probably remained a virgin into middle age. In the film Gillian injects love, music, and light into what is

depicted as David’s otherwise gray and miserable world; then toward the end of the story, they are shown having sex.

But perhaps the real reason for leaving Claire out was that even Hicks could not quite stomach the things that Gillian had

to say about her. Of the many cruel, spiteful things included by Gillian in her book, perhaps the most unpardonable is what

is written about Claire. Referring to her by her Hungarian name, Clara, Claire is described as “the world’s greatest bitch.”

Gillian quotes David as saying that marrying Claire was “the greatest mistake of his life” and that their marriage was “made

in hell and consecrated by and presided over by the Devil.” She writes that Claire “would publicly ridicule and bully” David

and that “David shivered at the memory” of Claire.

Just in case we miss the point, Gillian has entitled the chapter about Claire “Made in Hell,” but opens it with a line about

herself: “David was totally

Joyeux’

about my decision to marry him.”

Not surprisingly, Claire is distraught by what has been written about her. In its first few months Gillian’s book sold an

astonishing 60,000 copies in Australia alone and was high up on the best-seller lists in the United States and several other

countries. Claire told me that as a result she has suffered enormous distress and all kinds of medical problems. She asked

the publisher to remove the sections referring to her from the book, as well as demanding an apology from Gillian. Both requests

have been refused. (At least four other people, including myself, have written to the Australian publisher, Penguin, to complain

about the way we are portrayed in Gillian’s book. I have also agreed to honor Claire’s request not to reveal her last name

as she has already received more than enough harassment from the press and others as a result of Gillian’s book.)

“David’s mind has been poisoned against me by Gillian,” says Claire. “What she quotes David as saying is pure fabrication

and fantasy. She has simply put the words into his mouth. It’s very easy to get David to agree to anything. He would mimic

everything put to him. As for the Tactual’ claims in Gillian’s book, such as the one that I sold David’s piano in order to

make some money for myself, these are too ludicrous to be dignified with a reply. I think everyone can see who is making the

money.”

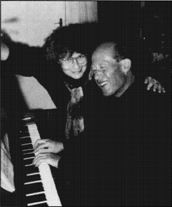

(From cover)

Margaret with David at his

beloved piano in August 1996.

(MELVYN TUCKEY)

Peter Elias Helfgott, probably on his way

back into Poland to see his family again.