the Emigrants (24 page)

Authors: W. G. Sebald

back to those days, I see shades of blue everywhere - a single empty space, stretching out into the twilight of late afternoon, crisscrossed by the tracks of ice-skaters long vanished.

The memoirs of Luisa Lanzberg have been very much on my mind since Ferber handed them over to me, so much so that in late June 19911 felt I should make the journey to Kissingen and Steinach. I travelled via Amsterdam, Cologne and Frankfurt, and had to change a number of times, and sit out lengthy waits in the Aschaffenburg and Gemünden station buffets, before I reached my destination. With every change the trains were slower and shorter, till at last, on the stretch from Gemünden to Kissingen, I found myself in a train (if that is the right word) that consisted only of an engine and a single carriage - something I had not thought possible. Directly across from me, even though there were plenty of seats free, a fat, square-headed man of perhaps fifty had plumped himself down. His face was flushed and blotched with red, and his eyes were very close-set and slightly squint. Puffing noisily, he dug his unshapely tongue, still caked with bits of food, around his half-open mouth. There he sat, legs apart, his stomach and gut stuffed horribly into summer shorts. I could not say whether the physical and mental deformity of my fellow-passenger was the result of long psychiatric confinement, some innate debility, or simply beer-drinking and eating between meals. To my considerable relief the monster got out at the first stop after Gemtinden, leaving me quite alone in the carriage but for an old woman on the other side of the aisle who was eating an apple so big that the full hour it took till we reached Kissingen was barely enough for her to finish it. The train followed the bends of the river, through the grassy valley. Hills and woods passed slowly, the shadows of evening settled upon the countryside, and the old woman went on dividing up the apple, slice by slice, with the penknife she held open in her hand, nibbling the pieces, and spitting out the peel onto a paper napkin in her lap. At Kissingen there was only one single taxi in the deserted street outside the station. In answer to my question, the driver told me that at that hour the spa clientèle were already tucked up in bed. The hotel he drove me to had just been completely renovated in the neo-imperial style which is now inexorably taking hold throughout Germany and which discreetly covers up with light shades of green and gold leaf the lapses of taste committed in the postwar years. The lobby was as deserted as the station forecourt. The woman at reception, who had something of the mother superior about her, sized me up as if she were expecting me to disturb the peace, and when I got into the lift I found myself facing a weird old couple who stared at me with undisguised hostility, if not horror. The woman was holding a small plate in her claw-like hands, with a few slices of

wurst

on it. I naturally assumed that they had a dog in their room, but the next morning, when I saw them take up two tubs of raspberry yoghurt and something from the breakfast bar that they had wrapped in a napkin, I realized that their supplies were intended not for some putative dog but for themselves.

I began my first day in Kissingen with a stroll in the grounds of the spa. The ducks were still asleep on the lawn, the white down of the poplars was drifting in the air, and a few early bathers were wandering along the sandy paths like lost souls. Without exception, these people out taking their painfully slow morning constitutionals were of pensioner age, and I began to fear that I would be condemned to spend the rest of my life amongst the patrons of Kissingen, who were in all likelihood preoccupied first and foremost with the state of their bowels. Later I sat in a cafe, again surrounded by elderly people, reading the Kissingen newspaper, the

Saale-Zeitung.

The quote of the day, in the so-called Calendar column, was from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and read:

Our world is a cracked bell that no longer sounds.

It was the 25th of June. According to the paper, there was a crescent moon and the anniversary of the birth of Ingeborg Bachmann, the Austrian poet, and of the English writer George Orwell. Other dead birthday boys whom the newspaper remembered were the aircraft builder Willy Messerschmidt (1898-1978), the rocket pioneer Hermann Oberath (1894-1990), and the East German author Hans Marchwitza (1890-1965). The death announcements, headed

Totentafel,

included that of retired master butcher Michael Schultheis of Steinach (80). He was extremely popular. He was a staunch member of the Blue Cloud Smokers' Club and the Reservists' Association. He spent most of his leisure time with his loyal alsatian, Prinz. -

Pondering the peculiar sense of history apparent in such notices, I went to the town hall. There, after being referred elsewhere several times and getting an insight into the perpetual peace that pervades the corridors of small-town council chambers, I finally ended up with a panic-stricken bureaucrat in a particularly remote office, who listened with incredulity to what I had to say and then explained where the synagogue had been and where I would find the Jewish cemetery. The earlier temple had been replaced by what was known as the new synagogue, a ponderous turn-of-the-century building in a curiously orientalized, neo-romanesque style, which was vandalized during the Kristallnacht and then completely demolished over the following weeks. In its place in Maxstrasse, directly opposite the back entrance of the town hall, is now the labour exchange. As for the Jewish cemetery, the official, after some rummaging in a key deposit on the wall, handed me two keys with orderly labels, and offered me

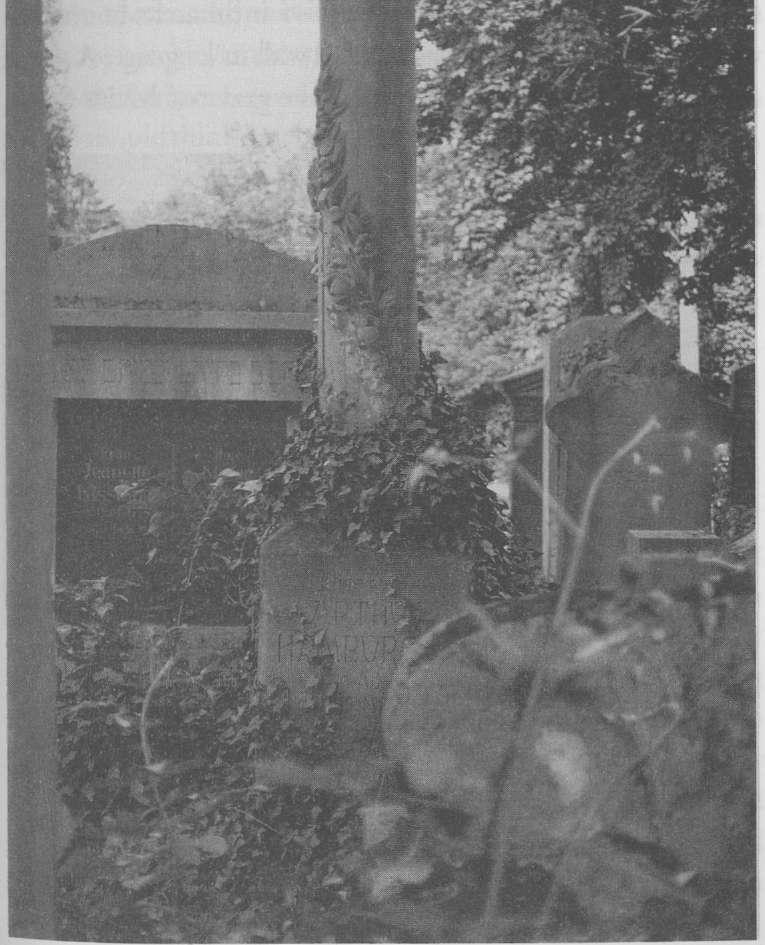

the following somewhat idiosyncratic directions: you will find the Israelite cemetery if you proceed southwards in a straight line from the town hall for a thousand paces till you get to the end of Bergmannstrasse. When I reached the gate it turned out that neither of the keys fitted the lock, so I climbed the

wall- What I saw had little to do with cemeteries as one thinks of them; instead, before me lay a wilderness of graves, neglected for years, crumbling and gradually sinking into the ground amidst tall grass and wild flowers under the shade of trees, which trembled in the slight movement of the air. Here

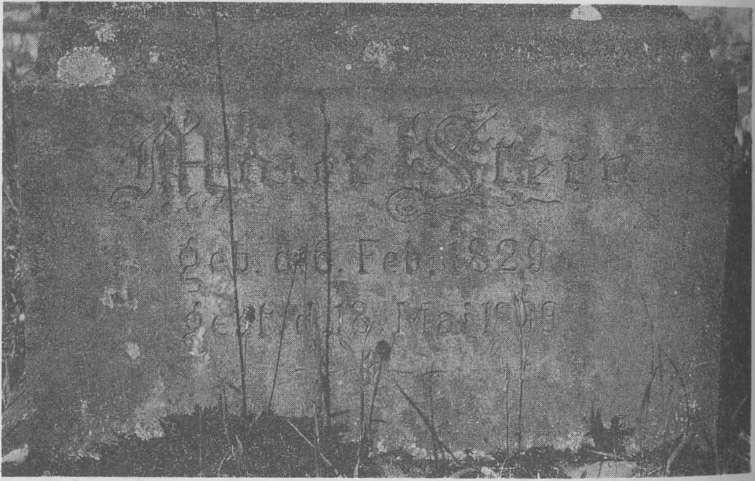

and there a stone placed on the top of a grave witnessed that someone must have visited one of the dead - who could say how long ago. It was not possible to decipher all of the chiselled inscriptions, but the names I could still read -Hamburger, Kissinger, Wertheimer, Friedlànder, Arnsberg, Auerbach, Grunwald, Leuthhold, Seeligmann, Frank, Hertz, Goldstaub, Baumblatt and Blumenthal — made me think that perhaps there was nothing the Germans begrudged the Jews so much as their beautiful names, so intimately bound up with the country they lived in and with its language. A shock of recognition shot through me at the grave of Maier Sterm,

who died on the 18th of May, my own birthday; and I was touched, in a way I knew I could never quite fathom, by the symbol of the writer's quill on the stone of

Friederike

Halbleib, who departed this life on the 28th of March 1912-I imagined her pen in hand, all by herself, bent with bated breath over her work; and now, as I write these lines,

it

feels as if / had lost her, and as if / could not get over the los.

1

despite the many years that have passed since her departure. I stayed in the Jewish cemetery till the afternoon, walking up and down the rows of graves, reading the names of the dead, but it was only when I was about to leave that I discovered a more recent gravestone, not far from the locked gate, on which were the names of Lily and Lazarus Lanzberg, and of Fritz and Luisa Ferber. I assume Ferber's Uncle Leo had had it erected there. The inscription says that Lazarus Lanzberg died in Theresienstadt in 1942, and that Fritz and Luisa were deported, their fate unknown, in November 1941. Only Lily, who took her own life, lies in that grave. I stood before it for some time, not knowing what I should think; but before I left I placed a stone on the grave, according to custom.