The New Policeman (16 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

Larry O’Dwyer walked slowly but, he hoped, authoritatively, up and down the main street of Kinvara. Everyone who passed stopped to ask him for the latest news and to give him their theory on the missing people. This, Larry was almost certain, was not why he had become a policeman, but he succeeded in remaining courteous and respectful. Only one person tried his patience, and that was Thomas O’Neill.

He began by asking the usual questions and continued on to give Larry an account of one of the widely accepted theories. But as he spoke he looked at him rather too closely for comfort.

“I know you,” he said, when Larry had congratulated him on the pertinence of his theory and assured him that he and his colleagues would bear it in mind. “It’s coming to me now.”

Larry hoped that it wasn’t. He could really do without the kind of trouble that a man of Thomas’s age and status could create for him. Spotting Phil

Daly on the other side of the road, he made rapid excuses and crossed over to talk to him.

Phil asked the usual questions, but if he had a theory he kept it to himself. “I was looking for you last week,” he said. “I wanted to invite you to a céilí.”

“Oh,” said Larry. “I wish you’d found me.”

“Yeah,” said Phil ruefully. “It was good. But it was at the Liddy house. I don’t suppose there’ll be another one now. Not for a good while, anyway.”

“You never know,” said Larry. “I’d say the lad could still turn up.”

The rest of the day sped past, despite the lack of activity. The only noteworthy thing that happened was the sudden appearance, from the quiet street that ran down past the community center, of a white donkey. Nobody knew who owned it or where it had come from. Very few people kept donkeys anymore.

It shouldn’t really have been police business, but since Larry was in the village anyway and had nothing much else to do, he got drawn into the debate about what should be done with it. It was a placid creature and a source of great amusement to the schoolchildren, but it was a nuisance to traffic and couldn’t be allowed to stay there. Sergeant Early blew a minor

fuse when Larry radioed him for advice, and for a while Larry was at a loss to know what to do. He stood outside Fallon’s with his arm round the donkey’s neck until the word got around and one of the local horse owners came and agreed to take charge of it until someone came to claim it.

THE WHITE DONKEY

Kate Thompson

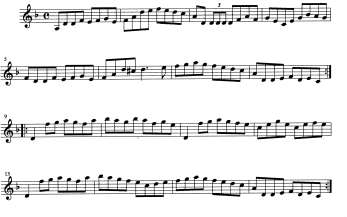

There was, after all, a pigeon on the gate. While he was waiting for Aengus, J.J. took out the fiddle and ran the bow over the strings to see what he could come up with. The notion still lingered in his mind that if he could only remember “Dowd’s Number Nine” the whole time situation might miraculously resolve itself. When he failed, he had a go at remembering some of the tunes he had played with the others in Winkles that evening, and when he came to a dead end with those, he played “The Pigeon on the Gate.”

“That’s the wrong ‘Pigeon on the Gate,’” said Aengus, emerging from the hazel.

J.J. looked at the bird. Aengus took the fiddle and played a different tune. It was in the same key and the

first few notes were the same, but it was a mellower, more haunting tune. J.J. hadn’t heard it before, but he had yet another version. He took the fiddle back. “Where’s this pigeon then?” he asked, and played it.

Aengus shrugged. “Could be anywhere.” J.J. played “The Bird in the Bush.” Aengus laughed and danced a few lively steps on the road. J.J. was enjoying himself, but Aengus took the fiddle back and put it away. “You’re a poor teacher,” he said. “Very slack for a ploddy.”

“A what?”

“A ploddy,” said Aengus. “You have a name for us. Did you think we wouldn’t have one for you?”

“But…ploddy?”

“Is it any worse than fairy?” said Aengus. He slung the fiddle over his shoulder again and they walked on up the road. There was something odd about him, and it was a while before J.J. realized what it was.

“You changed your shirt,” he said.

Aengus looked down at himself as though he wasn’t sure what he was wearing. “Oh, yes,” he said. “I didn’t mention that, did I?”

“Mention what?”

“The leprechaun laundry. That was my business with them. They wash clothes.”

J.J. found it unlikely, but who was he to argue? “They wash your shirts,” he said, “and you pay them with gold?”

“Well,” said Aengus, “that’s what they’ll be hoping, yes.”

Behind them the frantic hammering faded into the distance and died away. When they stopped again to wait for Bran, J.J.’s thoughts returned to the changelings.

“Do you go back for them?” he asked Aengus. “Your children?”

“No, no,” said Aengus. “We just forget about them. They come back when they’re ready.”

“What, you mean they just turn up?”

“They do. They’re usually about your age when they get here, give or take a year or two.”

“But how do they get through?” said J.J. “And how do they even know they’re…” He hesitated, then decided that, since Aengus had called him a ploddy, there were no holds barred. “How do they know they’re fairies?”

They had reached the highest point on the road and Aengus turned in at a gap in the hedge. There was a path, as there was in J.J.’s world, which led toward the hazel woods at the bottom of Eagle’s Rock.

“You know about cuckoos, I suppose,” said Aengus.

“A bit,” said J.J. “I know they lay their eggs in other birds’ nests.”

“They do,” said Aengus. “And then they head straight back home to Africa. The chicks hatch out in Ireland, grow up in Ireland, learn to fly in Ireland, and then, when they’re ready, they head off for Africa as well.”

“Really?” said J.J. “But how do they know how to get to Africa?”

“The same way our children know how to get here,” said Aengus.

“It must be some sort of instinct,” said J.J.

“It might be,” said Aengus, “though I suspect that word ‘instinct’ might be used by your scientists to explain any kind of animal behavior that they don’t understand. Did you know that cuckoos were originally from here?”

“No,” said J.J., though now that he was thinking about it he remembered that he’d heard them referred to as “fairy birds.”

Aengus paused to lift Bran into his arms. They were crossing some awkward, stony ground and she was having difficulty. “Same principle, you see?” he

said. “They used to lay their eggs in ploddyland and come home. Their chicks borrowed some of your time to grow up, then followed their parents back here.”

“Then why don’t they still do it?” asked J.J.

“Airplanes,” said Aengus, putting Bran carefully back onto her three feet.

“What about airplanes?” said J.J.

Aengus looked up. “Do you see any?” J.J. scanned the sky. “No.”

“There aren’t any, that’s why. We had to close the sky gates when your crowd learned to fly. It was way too dangerous.”

“There were sky gates?”

“All over the place,” said Aengus. “For the cuckoos. But we couldn’t have planeloads of ploddies landing in on top of us, could we? Besides, they’re dreadful, noisy, smelly things, the same airplanes. Sad, but we had to say good-bye to the cuckoos.”

They walked on along the stony path. It ran through a big rocky meadow; windswept and bleak in J.J.’s world but serene here, and littered with clover and cranesbill. There were no socks to be seen anywhere.

“How did you do it?” asked J.J. “Close the sky gates?”

“I don’t know,” said Aengus. “My dad takes care of

all that stuff. He had to close the sea gates as well when you started building submarines. The merrows are all stuck here now.”

“What if one of them was left open?” said J.J. “By mistake, I mean. Couldn’t the time be coming through there?”

“It wouldn’t follow,” said Aengus. “The time skin is the same there as it is down here. One of them did get left open for a while, actually. Dad just forgot about it. Quite a few planes came through before he copped on to it. The ploddies called it the Bermuda Triangle.”

“But that’s miles away,” said J.J. “How could the planes get into Tír na n’Óg?”

“Our world is the same size as yours, J.J. Same seas, same continents, same everything except time.”

J.J. sat down on a slab of rock. “That’s crazy,” he said. “That means the leak could be anywhere. Anywhere in the whole world!”

There was no answer. J.J. turned to where Aengus had been standing. Bran was lying in the grass, licking her injured leg, but Aengus was nowhere to be seen.

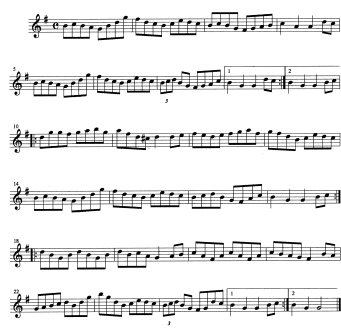

THE CUCKOO’S NEST

Trad

“Aengus?” he called.

“What?” Aengus was standing right behind him, exactly where he had expected him to be when he turned around. But he hadn’t been there last time he looked, he was certain of it.

“I didn’t see you there,” said J.J. “My eyes must be playing tricks on me.”

“How odd,” said Aengus. “You’d never get to the bottom of what goes on in a ploddy mind.”

He walked on across the hillside, and J.J. followed. Ahead of them Eagle’s Rock rose up, a sheer cliff climbing out of the scrubby woods that ran along its base. There was no breeze, and the silence was absolute until a spine-tingling cry rang out from the crag. Bran’s hackles stood up and she growled.

It was the first sound that J.J. had heard her make.

“What was that?” he asked Aengus.

“It wasn’t a leprechaun, anyway,” said Aengus. “They don’t come up this high.”

They went on again. Bran’s hackles stayed raised, but there was no more sound from the rock. At the edge of the wood, where the little path ran in toward Colman’s cave, Aengus turned to J.J.

“Where was it you smelled the tobacco smoke?” J.J. knew those woods well in his own world. There had been a time when he visited them a lot, just to breathe the cool air and enjoy the undisturbed mystery of the place. But here they gave him the creeps. He wasn’t at all sure he wanted to go in.

“About halfway along, I think,” he said. “But I might not have smelled anything, now I come to think of it. I could have imagined it.”

“That’s what ploddies always say about leaks,” said Aengus. “Come on.”

He led the way in among the trees. The sun’s light slanted through the branches, covering the mossy floor with patchy shadows. Bran was still on edge and J.J. sensed that, despite his nonchalant air, Aengus was as well. As they passed a young blackthorn, a little

flock of wrens ticked and whirred at them like a bush-full of tiny clocks. Other than that there was no sound in the woods, apart from their own careful footsteps. “Around here?” said Aengus after a while.

“A bit farther on, I think,” J.J. whispered. “It’s hard to tell.”

After another hundred meters he pulled at Aengus’s elbow. “About here, I think.”

“Right.” Aengus stopped and looked all around. “I’m going to have to go through for a while.”

“Go through?” said J.J.

“I won’t be gone long, but I can’t check out the wall without going through it.” He handed J.J. the fiddle. “You’ll be safe enough here with Bran.”

“Okay,” said J.J.

“Don’t talk to any goats, all right?”

“Goats?” said J.J., but Aengus was already gone, slipping lightly away between the straight stalks of the hazel and then…

Where?

J.J. wished that Bran wasn’t so nervous. She was lying down again, but not in the usual way. She wasn’t resting. Her ears were pricked, and she was staring fixedly in the direction of the crag, as though expecting something to appear at any moment. J.J. sat on a

mossy rock. It was damp, despite the dryness of the day, but he didn’t get up again. He was developing the most awful feeling that he was being watched.

He put the fiddle case down on the ground, but he wasn’t inclined to open it. He felt far too exposed. The damp was soaking into his jeans, but still he stayed where he was.

“Good girl, Bran,” he said quietly, as much to mask the silence as anything. In response, she growled again, a low rumble from deep in her chest. J.J. broke out in goose bumps. Bran was staring through the trees. There was something there.