The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year (16 page)

Read The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year Online

Authors: Linda Raedisch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

122 Reindeer Games

On Prancer!

Thanks to the names given them by Clement Moore, not to

mention the work of Arthur Rankin and Jules Bass, we tend

to think of the eight tiny reindeer pulling Santa’s sleigh as males, but the females of

Rangifer tarandus

also sport modest antlers with which they protect their calves from potential predators. Reindeer calves are conceived in September and born in May, so the does are already a few months gone by Christmas Eve. I doubt Santa would want to endanger

the health of a gestating female by asking her to pull a fully loaded sleigh around the globe, so Dasher, Dancer and all

the rest are probably males.

They cannot, however, be bulls, for all that autumnal

rutting has left the mature, sexually potent males too weak to pull the sleigh. The exhaustion following the frenzy of courtship shows itself in the bulls’ antlers, which by early winter have begun to drop off. And when did you ever see

one of Santa’s reindeer with only half a rack?

There is only one kind of reindeer suitable for pull-

ing Santa’s sleigh and that is the

harke

, or castrated male.

The harke, whose testicles were traditionally bitten off by the herdsman, is real Christmas card material. With few

demands on his energy, he is able to keep his fine antlers as well as a thick coat and enough body fat to keep him

going on his world tour. A harke in harness looks very festive indeed, for the old time reindeer harness is an elaborate affair, the leather collar adorned with appliqué, couched tin thread and a variety of bells.

Reindeer Games 123

The Witch’s Drum

Compared to the harke in full regalia, the reindeer in the following craft is a bit of a Plain Jim. That’s because he was inspired by the many reindeer one can see painted on the

Sami shaman’s drum, sometimes known as a “magic drum”

or even a “witch’s drum.” As large as a small child and

roughly oval in shape, the skin of the drum was smoked to

a snowy whiteness then painted all over with figures drawn in the artist’s saliva which was made red by the chewing of alder bark. There are anthropomorphic figures, mountains,

bodies of water, birds, animals, but most of all reindeer. The edge of the drum was hung with amulets made from fur,

hooves and bone.

One of the purposes of this drum was to divine the

future. When the noide had entered his trance, he placed

an

arpa

, a triangular piece of metal or bone (not unlike the planchette from a Ouija board) upon the drum skin. Then

he struck the drum with a stick shaped like a Thor’s ham-

mer. The arpa would then jump about from picture to pic-

ture, giving the drummer an idea of what to expect in the

coming season. Sometimes, the gods spoke through the

drum to request a sacrifice.

We hear quite a bit about these “witches’ drums” in the

Norse sagas and again in the seventeenth century when

Protestant proselytizers took an interest in burning them.

Since they were made of organic material, it’s impossible

to say how long such painted drums had been in use, but

Stone Age pictures of reindeer similar to those seen on the drums have been found in red ochre on sheltered rock faces throughout Lapland.

124 Reindeer Games

Craft: Sacrificial Reindeer Ornament

For this craft, I have suggested a red ribbon in token of the blood which was offered to the Yuletide People in ancient

days, but it need not be a plain red ribbon. The Sami are

famous for their brightly colored tablet-woven bands which often incorporate metallic thread, so don’t be afraid to be festive.

Tools and Materials:

2 squares white felt

Clear tape

Scissors

Needle and white thread

5–6 cotton balls

¼ inch wide red cloth ribbon, about 6 inches long

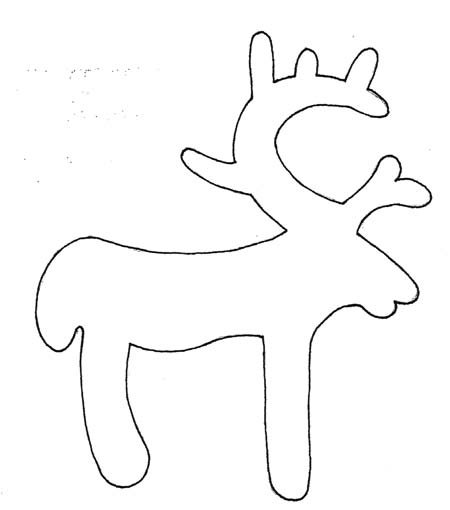

Trace and cut out the template, then stick it to your felt with a generous number of clear tape strips. This beats tracing the image onto the felt which is more work and would leave pen marks on your finished product.

Cut out the antlers first since they are the most intri-

cate. When you have cut out two reindeer this way, lay them one atop the other, making sure all the details line up, and whip-stitch them together. Stitch the antlers first.

Reindeer Games 125

Sacrificial Reindeer Figure 1

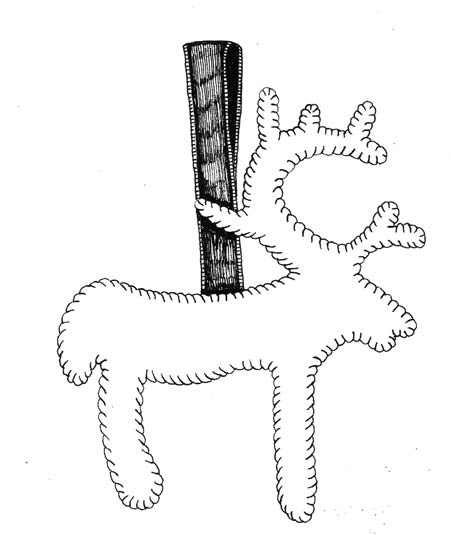

Stuff the figure with wisps of cotton ball as you go. Use

a toothpick to help push the stuffing in. The points of the antlers will be too skinny to stuff.

Don’t forget to add the ribbon. Fold it in half and insert it in the reindeer’s back and whip-stitch right through it.

Hang your finished reindeer on your Christmas tree or

one dedicated to the Yuletide People.

126 Reindeer Games

Sacrificial Reindeer Sketch 2

The Horns of Abbots Bromley

Until about 1660, reindeer were an integral part of the

Christmas season in the Staffordshire village of Abbots

Bromley. Since then, the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance has

been held in early September, but in the late sixteenth century, it was performed at New Year’s and Epiphany. At that time, and possibly earlier, the six pairs of antlers were set in carved wooden heads, three painted red, three white, the heraldic colors of the village’s most prominent families.

The colors have since changed, but, when not in use, the

antlers are still kept in St. Nicholas’ Church.

Reindeer Games 127

The dance takes place outside hallowed ground. The

Deer Men, as they are called, are not the only participants in this dance, but they are certainly the main attraction.

They do not actually wear the antlers, but hold the sticks with the wooden heads at chest level while supporting the

weight of the antlers on their shoulders. In

The Lost Gods

of England

, Brian Branston relates the Horn Dance to an incident in 1255 in which a company of thirteen cheeky

poachers mounted a stag’s head on a pole in the middle of

Rockingham Forest in apparent mockery of the king. Bran-

ston goes on to ask the reader if it is too much to believe that in both cases the participants were acting as shamans in a once widespread prehistoric tradition. The fact that

the Abbots Bromley horns are reindeer antlers would sug-

gest that it is not, since reindeer have been extinct in England for thousands of years. Unfortunately for Branston,

the antlers were not actually handed down from the Age of

the Cave Painters. They are, however, quite old, having been carbon dated to the eleventh century, at which time they

belonged to six castrated males—exactly the kind of rein-

deer that might be expected to pull Santa’s sleigh. Even if one were to dispute the dating, England’s Ice Age hunters

never domesticated the reindeer and therefore would not

have been in a position to castrate any of them.

The Abbots Bromley antlers must have been acquired

through trade or as part of some unusual dowry. Most

likely, Staffordshire was not their first stop on their way down from Lapland. Had they still been attached to the

skulls, they might very well have ended up in some hunt-

ing lodge in Needwood Forest, but free-floating rein-

128 Reindeer Games

deer antlers have little commercial value unless one plans to carve them into combs, buttons or cup handles. Whoever installed them at Abbots Bromley would have been a

connoisseur of the unusual, or he was in his cups when he

bought them. I would not be at all surprised if they had

been won in a card game.

Another theory goes that they were brought to town by

a settler from Norway. White and red are, after all, the traditional Scandinavian Yule colors. Is it too much to believe that the same settler commissioned the first seasonal Horn Dance to remind him of his homeland? No doubt it is.

Nowadays, the heads are painted white and brown, not

because there are no more Norwegians in the village but

because those prominent families of the sixteenth century

have dwindled into oblivion.

The earliest written record of the Horns’ appearance in

what was then known as the Abbots Bromley Hobby-horse

Dance dates to around 1630. The dance itself was already

mentioned in 1532, but we cannot be sure the horns were

part of it. As elsewhere in England, a hobby-horse remains the central figure in the dance, though most people now

come to see the Horns. And that is exactly why the Abbots

Bromley dancers would have incorporated them into their

ritual in the first place: because they had them, and the

other Midlands villages did not. The purpose of the performance is clearly described in the account from the seven-

teenth century: to solicit monetary donations which went

to spruce up the church and provide cakes and ale for the

poor.

Reindeer Games 129

Happily, these details meant little to the folklorists who first poked their noses and their pens into the histories of such village traditions. To them, as to the later Branston, the Horns and the dancers in their gaily patterned breeches were relics of Europe’s long shamanic winter. Such a capti-vating idea is hard to dispel. Eric Maple, writing in 1977, a full twenty years after Branston, refers to the Horn Dance as “Another survival from ancient times.”31 Maple, who

regards the performance as a fertility rite, reckons that the Deer Men’s overriding mission is to carry blessings to the fields.

In the end, whoever hauled the six pairs of antlers into

town all those centuries ago should now be hailed as a hero, for while hundreds of other hobby-horse dances have bitten the dust, the Horn Dance is still going strong. And

though they probably weren’t expecting it, it appears that the good citizens of Abbots Bromley have received a lasting gift from the Yuletide People.

31. See Eric Maple,

Supernatural England

, pages 41–42. While Maple’s telegrammatic style can be a time saver, I recommend Ronald Hutton’s

The Stations of the Sun

, pages 90–91 for a more sober treatment of the subject.

A Christmas Bestiary

A bestiary was a book of animals: not a catalogue of accu-

rate descriptions, but a flight of medieval fancy in which the reader was supposed to draw Christian lessons from

the habits and aspects of all sorts of creatures from lions to roosters to mermaids. There is no such moralizing in

this chapter, though there is plenty of fancy. The fancies are not mine but those of our ancestors who, unlike the clerical bestiary author locked in his scriptorium, all had up-close, personal encounters with the animals in question: the horse, the goat, the pig or boar, the cat, the wolf and the dog.

The names of four of these creatures—I suppose you

could call them monsters—are preceded by the world

“Yule.” In the case of the Yule Buck and Yule Cat, these

are direct translations from the various Scandinavian lan-

guages. I use the names “Yule Horse” and “Yule Boar” as

generic terms encompassing a variety of costumes, charac-

ters and phenomena. Of the four, the Yule Boar is certainly

131

132 A Christmas Beastiary

the most confounding, for within the tradition we find not just a spectral Christmas pig but also a boar-shaped loaf of bread (or marzipan) and the unquiet ghost of a child. One

might not immediately associate the spectral dog or the

werewolf with Christmas, but they each once held a place

therein, back in the days when the streets were not yet festooned with lights during the Twelve Nights of Christmas