The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year (20 page)

Read The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year Online

Authors: Linda Raedisch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

According to legend, the first “Lussi,” as she was known in earlier times, was a local girl who appeared in the pre-dawn hours of a winter’s morning to deliver food to the starving villagers of western Sweden. These days, she shows up with a coffeepot and a basket of saffron buns or

Lussekatter

. These 35. See “Boys blocked from bearing ‘girls-only’ Lucia crown” at http.//www.thelocal.se/16308/20081212/.

158 Winter's Bride

“Lussi cats,” may point to the Norse fertility goddess, Freya, whose chariot was pulled by cats. Unfortunately, there is no record of such “cat buns” before 1620, at which time they

were baked for St. Nicholas’ Day in the sometime German,

sometime Danish province of Holstein.

Recipe: Lussekatter

These buns come in a wide variety of traditional shapes

bearing such imaginative names as Goat Cart, Peacock and

Priest’s Hair. The general name by which they are known is Lussekatter, meaning “Lucy cats.” The most common shape

is the “S” scroll presented here, which many Swedes identify as the Cat itself. Others call it the boar or simply the Twist.

Two “C” scrolls placed back to back might also be the Cat

or a set of Wagon Wheels. Because they’re labor intensive, Lussekatter can be made ahead of time, frozen and warmed

in the oven before the sun comes up on December 13. Serve

them with coffee and candlelight.

Ingredients:

½ cup (1 stick) unsalted butter plus a little more for

greasing

1 cup whole milk

1 goodly pinch saffron threads

5 cardamom pods or ½ teaspoon ground cardamom

(both optional)

½ cup sugar plus a little more for sprinkling

1 package active dry yeast

2 eggs, beaten, plus 1 egg white for glaze

4–4½ cups white flour

1⁄3 cup dried currants

Winter's Bride 159

Put the stick of butter in a small pot with the milk and heat on low just until the butter is melted. While you are waiting, crumble the saffron threads between your fingers or

grind them in a small mortar and pestle, then add them to

the butter/milk mixture and let stand. Spilt open your cardamom pods, if you are using them, and let the dark seeds

drop into the mortar. Crush. (No need to wash the mortar

and pestle in between the saffron and the cardamom.) Mix

the crushed cardamom seeds, sugar, yeast and one cup flour in a large bowl. Gradually stir in the warm saffron mixture.

Add beaten eggs and the rest of the flour a little at a time.

On a floured surface, knead the dough for about 10

minutes. Shape into a ball and place in a large, butter-

smeared bowl. Cover with a damp towel and leave in a

warm place to rise for about 45 minutes. Punch the dough

down and turn onto a lightly floured surface. Cover with

the towel and let rest about 5 minutes.

In the meantime, soak the currants in a bowl with hot

water. After 5 minutes, drain currants and set aside.

Pinch off a piece of dough to make a ball slightly larger

than a golf ball. Roll it into a rope between your hands and shape into an “S” scroll or, if you prefer, make a slightly more realistic cat’s head by flattening a small ball for the cat’s face, then pinching two smaller balls into ears. Place buns on a greased or foil-lined cookie sheet.

Cover your first sheet of buns with the damp towel and

let rise about 10 minutes while you prepare the second sheet.

160 Winter's Bride

Lussekatter

Just before you put your buns in the oven, brush them

with a beaten egg white and firmly press dried currants into dough for accents. Sprinkle buns with sugar and bake at

375 F for 10–15 minutes.

Night Walks with Heavy Steps

Like Denmark, Norway adopted the modern Lucia pro-

cession during World War II, thereby eclipsing the distant memory of a much older, darker spirit. This Lussi or Lussi-brud, i.e. “Lucy Bride,” was the witch-like leader of the

Lussiferd

, her own special detachment of the Wild Hunt. On December 13, this troop of goblins swept down on the Norwegian farmhouses to help themselves to bread and beer. If

Winter's Bride 161

there were any naughty children inside, Lussi herself might slip down the chimney to teach them a lesson.

“Night walks with heavy steps,” opens one of sev-

eral Scandinized versions of the old Neapolitan folk song,

“Santa Lucia.” In addition to marking the winter solstice

Old Style, December 13 was also one of the medieval Ember

Days, fasting days interspersed throughout the seasons to

remind humankind to repent. Cookies, buns and fish were

all right, but meat was forbidden. On Ember Days, the rich were supposed to give food to the poor, just as the legend-ary Lucia doled out loaves from her basket. Whether the

night of the full moon, solar event, cross-quarter day or one of that handful of leftover days at the end of the year, whenever a date was designated as extraordinary, the door was

left open to supernatural interference. As one of the Ember Days

and

the longest night of the year,

Lussinatt

was double trouble.

In Latvia, the werewolves came out on St. Lucy’s Eve,

while in Austria, as in old Norway, it was a night of witches.

In the mountains, things were relatively calm, but where the land flattened out toward the Hungarian plain, it was necessary to carry a frying pan full of glowing coals and blackthorn (

Prunus spinosa

) twigs through the house to smoke out those witches and goblins that might otherwise plunder the winter stores. In southern Austria, large round pancakes were baked in the hot ashes of the fireplace—the sun goddess’ wagon wheels, perhaps?—and a braided yeast bread

known as a

Luziastriezel

was baked as an antidote for the

162 Winter's Bride

bite of a rabid dog.36 To the north and east in Burgenland, it did not matter how many pancakes you made or how thick

the smoke rolling through the parlor; you could still expect a visit from the dreaded

Lutzelfrau

.

The Lutzelfrau

Known also as

Fersenlutzel

or “Heel Lucy” because she threatened to cut your hamstrings, and

Budelfrau

and

Pudelmutter

, an old mother who let presents rain down from her voluminous skirts, this witch was both discipli-narian and gift-giver in one. If you were lucky, you would never see her; she would throw her gifts in at the door

which had been mysteriously left ajar. But more often she

would step inside in all her horrific glory.

Here she comes, an old peasant woman in kerchief,

mask and ash-smeared face. She appears completely for-

eign, for surely no one so ugly has ever lived in the vil-

lage. She certainly looks nothing like the teenaged sister or housemaid who slipped out a little while ago and hasn’t come back yet. First, this pushy old hag inspects the floors, the furniture, the cupboards and the dishes inside them to make sure everything has been properly washed, dusted,

waxed and polished. Then she turns her attention to the

children. Have they also been scrubbed? Have they been

sweeping, studying, praying, obeying their parents and

36. There are a handful of ancient goddesses and goddess-like figures who often appeared with dogs, among them Diana, St. Wal-burga and the Lowland Nehalennia. The dogs might reflect these goddesses’ early identities as huntresses or as queens of the dead, for the dog was a popular escort to the underworld. Going her own way was the fertility goddess Freya with her string of cats.

Winter's Bride 163

getting to bed on time? Convinced that all is in order, she finally decides against abducting any of the children.

Before she goes, she gives her skirts a shake, letting fall an abundance of sweets, fruits and nuts interspersed with

turnips and potatoes. The root vegetables are seized by the older children who know there are sure to be coins hidden

inside. As the children scramble for the prizes rolling all over the floor, the Lutzelfrau disappears. A little while later, the older sister returns—and didn’t she just pass the strang-est character on the way home?

Lucka

Yet another sort of Lucy haunted the formerly German-

speaking areas of Bohemia. Like her Austrian counterparts, the Lucka of Neuhaus was neither young nor pretty, and

underneath her skirts she was not even female. Though the

Lucka, too, has taken a form of the saint’s name, she is more closely related to the old goddess-cum-folk figure, Perchta, specifically, Schnabelpercht or “Beak Perchta.”

The beak remained a prominent feature of the nine-

teenth century Bohemian Lucka, and what a beak it was,

concealing all but the piercing eyes of the impersonator

who, as a rule, was a teenaged boy. The wooden framework

of the beak was covered by a white handkerchief with two

eyeholes cut in it. This was knotted at the back of the neck, after which a large white kerchief was stretched over the

head and tied either under the chin or on top of the head. A woman’s dress and cloak completed the costume. By holding the point of the beak’s framework in his mouth, the

actor could make the pieces clack noisily as he inspected the

164 Winter's Bride

house, stirring up any lingering dust on the furniture with his

Federwisch

or “feather-wipe.” This was not the inef-fectual feather

duster

with which French maids flap about the house but the last joint of a goose’s wing with feathers intact, yet another relic of the bird goddess.

In fact, Lucka may have had another more mysterious

reason for making sure the floors were swept clean: she

did not want anyone to see what sort of footprints she left.

But if there was snow on the ground, as there was sure to

be during Advent in Bohemia, her splayed foot might still

leave behind the pentangular

Drudenfuss

or, “Drude’s foot,”

a sure sign that a

Drude

or bird-woman had passed that way. On December 13, the Drudenfuss was also a Christian

talisman, for the five points of the star correspond to the five letters in the saint’s Latin name, “Lucia.”

Craft: Lucka Mask

Here is a paper version of the old Bohemian disguise which was made of wood splints and linen. If you think you might not have a chance to wear your Lucka mask—who has the

time these days?—you can use smaller circles and make a

few maskettes to hang around the house from December 12

until Christmas Eve.

Tools and Materials:

2 large sheets watercolor or heavy drawing paper

Dinner plate for tracing

Cake plate or round serving platter, also for tracing

Pencil

Scissors

Ruler

Winter's Bride 165

Glue

X-acto or other craft knife

Hole puncher

White yarn or ribbon

Silver glitter, q-tip (both optional)

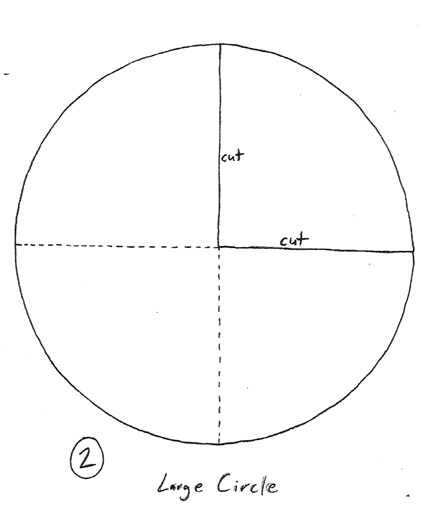

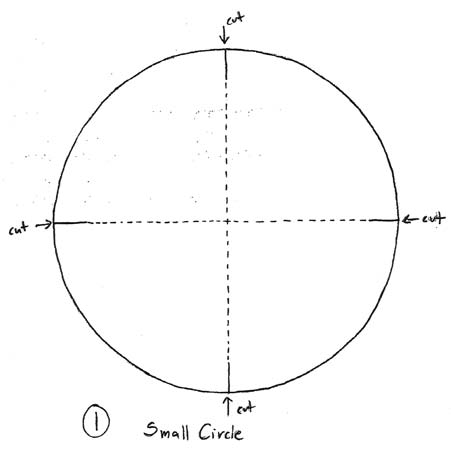

Trace the dinner plate and the cake plate on the two sheets of paper to make one small and one large circle. Cut both

circles out. Fold each circle into quarters and unfold. The dotted lines in Figures 1 and 2 show the creases.

Lucka Mask Figure 1

On the small circle, make four inch-long cuts from the

edge inward, as shown by the solid lines in Figure 1. On

the larger circle, cut out one quarter. (Figure 2) You will only need the other three quarters if you are going to make