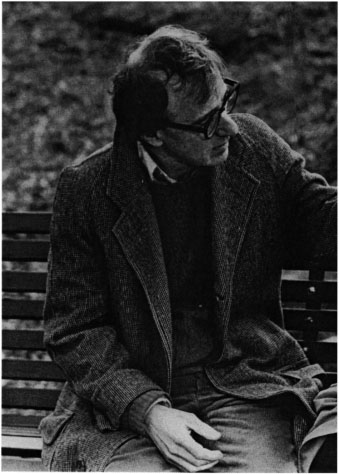

The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (25 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

The reconciliation of Elliot and Hannah stands on the extremely tenuous ground of her ignorance of his year-long affair with her sister, a disparity in knowledge which must, at the very least, adversely affect the two sisters’ relationship with each other as well.

29

Both of the marriages which this third Thanksgiving’s guest list ratify promise to founder on the same problem that doomed Lee’s previous relationship (her need to take as lovers substitute father figures, the latest a Columbia professor) and haunted Holly’s relationships with men: their parents’ refusal to acknowledge them, a new cycle of which will be initiated at this closing celebration by Norma’s preprandial toast announcing Hannah’s role in

Othello

. The primary source of tension in Norma and Evans marriage—her drinking—resurfaces at the final Thanksgiving as well, Norma holding a glass of booze from the bottle sitting on the piano as Evan performs “Isn’t It Romantic?” (It is, so long as you ignore the underlying strains existing in the scene.) Somewhat like Lear’s ceremonial division of his kingdom, or the shimmering wedding of Ben’s daughter in

Crimes and Misdemeanors

at which conspirator-in-murder Judah is a venerated and celebrated guest, the beautiful ceremony which opens

Hannah and Her Sisters

, we realize after watching two more of them, creates order at the expense of veracity, artificially mutes too many human realities at play in the room, represents a too great willingness to disregard problems in the name of projecting an illusory decorum. The holiday good cheer which seems to resonate in the film’s ending carries with it opposing undercurrents of falsity and doubt; Hannah, the founder of the feast as well as the putative object of its celebration, occupies the center of the conflicting messages of

Hannah and Her Sisters

.

Allen has been remarkably forthright in acknowledging that for both himself and Farrow, Hannah remained something of an enigma. “We couldn’t find a clear handle on [her character],” he told Bjorkman. “I could never decide whether Hannah was good or bad. It was very hard for me to know whether Hannah was a good sister or a bad sister.”

30

Given that Hannah is all but universally praised by the characters in the film for all of her other characteristics—generosity, sensitivity, maternal instincts, competence, homemak- ing skills, acting ability, and personal independence—the trait in contention is clearly the one articulated by Elliot: “Its hard to be around someone who gives so much and-and needs so little in return.”

“But look—I have enormous needs,” Hannah responds.

“Well, I can’t see them, and neither can Lee or Holly” (p. 157).

Hannah’s emotional self-containment is the quality which troubles her husband and apparently creates ambivalence as well in the screenwriter who, working with the inspiration of her model, Mia Farrow, imagined Hannah into being.

31

Whereas the more numerous voice-over passages allotted to Lee and Holly reflect their thoughts about themselves and their own circumstances, Hannah’s single soliloquy is devoted to a meditation upon her parent’s marriage, one that provides insight into a source of her own maternal dedication—Norma and Evan having been more interested in show business than in child-raising—but which offers no illumination of the “enormous needs” to which she lays claim. The loss of Elliots affections leaves her on the second—and most tension-ridden—of the three Thanksgivings, confessing to him, “Its so pitch black tonight. I feel lost” (p. 158).

Given that Lee had broken off the affair with him earlier in the evening, Elliot is liberated from his conflict between his erotic attachment to both sisters, allowing him to comfort and sincerely rededicate himself to Hannah. But the question that she asked him earlier continues to reverberate despite their reconciliation: “Do you, do you find me too … too giving? Too-too-too competent? Too-too, I don’t know, disgustingly perfect or something?” (p. 155). Interestingly, this is precisely the question some viewers have posed about her and, by extension, about the film that bears her name so centrally; it’s certainly the question that Allen is raising about it in expressing doubt about the effectiveness of the film’s ending. Another way to pose this question would be to ask whether Hannah’s projection of cultural serenity and orderliness is more significant than Mickey’s emanations of incessant, nearly masochistic self-questioning, of philosophical irresolution and uncertainty. Arguably, the text answers one way, the subtext another.

The ambiguity Allen admitted to in his feelings about Hannah’s character seems to be dramatized in the fact that both Mickey and Elliot (albeit only briefly) have fled from her, while her sisters betray her, respectively, in her husband’s arms and through an unflattering portrait of her in a play. It is, arguably, Hannah’s professional success, completely unimpeachable virtuousness and patient modesty which make her difficult for her lovers and sisters to contend with. In reconciling with her, Elliot says “I don’t deserve you,” and it appears that this conviction had played a precipitating role in his irrational pursuit of Lee, whose history of alcoholism and negligible worldly accomplishments make her a far less intimidating and much needier romantic partner than Hannah, celebrated star of Broadway stage and family hearth. However, it may be less her personal qualities to which they are so violently responding than to her not completely intentional epitomization of family—of human communality predicated upon home sharing. Given that she provides a home for her unenumerated natural and adopted children, Hannah is the magnet around which all the film’s issues of family congregate, Allen’s attitude toward the family consistently getting expressed through the characters’ relationships with and responses to her.

That Allen is articulating his own ambivalence toward family through his conflicted depiction of Hannah is the point being argued here, one made more uncomfortable by the fact that Hannah and Mia Farrow, in whose Manhattan apartment much of the movie was shot, often seem so inextricably linked to each other in the film. Maureen O’Sullivan, Farrow’s mother in both life and the film, accused Allen of the sort of excessively imitative art of which Holly’s two scripts are undeniably guilty, characterizing her daughter’s role of Hannah as “a complete exposure of herself. She wasn’t being anything—she was being Mia.”

32

Hannah is, of course, a fictional character, one who merely resembles, without replicating, an actual person. Nonetheless, it is difficult not to see significant convergences between Hannah’s characteristic docility and Farrow’s tendency to depict herself as acted upon more than acting throughout her memoir.

33

Underlying both character’s and author’s passivity lies a penchant, no doubt justified, to consistendy depict herself simultaneously as self-sacrificing mother and as victim-of-others. In her memoir, Farrow commented,”It was my mother’s stunned, chill reaction to the script [of

Hannah]

that enabled me to see how [Allen] had taken many of the personal circumstances and themes of our lives, and, it seemed, had distorted them into cartoonish characterizations…. He had taken the ordinary stuff of our lives and lifted it into art. We were honored and outraged.”

34

In obvious and less-than-obvious ways,

Hannah and Her Sisters

seems to confirm Farrow’s comment to Kristi Groteke: “I look at them [the films she made with Allen] and see my life on display for everyone to watch.”

35

It is Allen’s ambivalent attitude toward the life that Hannah/Farrow embodies which gets acted out in

Hannah and Her Sisters

.

Unlike the sudden and, in Hannah’s eyes at any rate, unambiguous resolution of her spiritual/marital crisis, the dramatization of Mickey’s dark night of the soul involves thoughts of suicide (“I just felt that in a Godless universe, I didn’t want to go on living” [p. 169]), and a comical attempt at self-destruc- tion, his psychic struggle culminating in a hard-won affirmation of the surfaces of life as “a slim reed to hang your whole life on, but that’s the best we have.”

37

(The emotional urgency of Mickey’s search contrasts as well with the dispassionate precision with which Elliot earlier articulates his conflict between Hannah and Lee, his mode of expression alone continuing to affirm the assumption of cultural elevation embodied by Hannah’s Thanksgiving: “For all my education, accomplishments, and so-called wisdom … I can’t fathom my own heart” [p. 144].) As he watches the Marx Brothers’ film, Mickey manages to affirm his life on remarkably similar grounds to those on which Elliot indicted his own: “I’m thinking to myself, geez, I should stop ruining my life … searching for answers I’m never gonna get, and just enjoy it while it lasts. And … then, I started to sit back, and I actually began enjoying myself” (p. 172). Nothing follows in the film to undermine or ironize this judgment, and it is with good reason that many critics tend to quote from this passage as if it were a sort of consummate Woody Allen creed. In fact, it is most certainly this affirmation of life (or, more exactly, of the Marx Brothers’ Jewish American comedic burlesque of it

38

) which subsequently culminates in Mickey’s interest in Holly, the union rendering possible both his readmission to Hannah’s family and the potential solution of his existential anxieties through fatherhood. Because of his existential baptism in

Duck Soup,

Mickey is back for another Thanksgiving dinner at Hannah’s. He’s going be a dad, and apparently all is right with the world: “The large family and the plentiful food” Douglas Brode contends, “suggest Mickey’s (and Woody’s) understanding of the need to rejoin the human community.”

39

But for all the engaging holiday felicity of this ending, there are sugges-tions in the unacknowledged tensions permeating the scene that for Mickey to rejoin Hannah’s family exacts an extraordinarily high price, since it implies repudiating the self-as-searcher, the identity which many of Allen’s protagonists assert. The cost of the effort to “enjoy [life] while it lasts” may necessitate his embracing of her family ethics reluctance to ask discomfiting questions—to believe as Hannah does that people should conceal their true feelings because others “don’t want to be bothered” with them. (Significantly, all that Mickey and his assistant, Gail—also Jewish—are depicted discussing are Mickey’s deeply felt personal dilemmas and conflicts, the humor of their dialogue predicated upon the classic Jewish American comic formula: talk about what the Goys

never

talk about, and you’ve got funny.)

The affirmation of family in

Hannah and Her Sisters

seems inextricably burdened with the values of this specific family, one with whom Allen has, at best, ambivalent sympathies. It almost seems as if Hannah’s family’s characteristic tactfulness and discretion have their equivalent in the plot’s reluctance to seriously engage some of the issues it has raised: even Di Palma’s justly praised rotating camera scene of emotional confrontation among the three sisters over lunch fails to bring into the open the primary tension underlying it: Lee’s continuing affair with Elliot.

40

In a decade when Hollywood was regularly turning out films—

On Golden Pond, The Hotel New Hampshire

—celebrating the family as a repository of human cohesiveness and order,

Hannah

is Allen’s sincere attempt to create a more substantial vision of that affirmation, his attempt to convince the viewer—and even more so, himself—of its validity. Holly’s disclosure of her pregnancy, then, represents the leap of faith Allen undertook—and would later regret undertaking—in order to register his endorsement of the family-as-repository-of-meaning. As if in retraction of the affirmative construction of family he’d attempted to create in

Hannah and Her Sisters,

three years later in

Crimes and Misdemeanors,

Allen proceeded to make a film in which a man complicit in a murder is released from the terrible guilt he experiences over the deed by the warmth, regard, and love of his family. In

Hannah,

Allen managed to push this affirmation as far as marrying Mickey to Holly and allowing himself the

deus ex machina

of her pregnancy revelation. However, it seems crucial to recognize that the film stops short of visualizing Mickey seated at Hannah’s groaning board of holiday feast, festivity, and unconfronted tensions—that it refused to portray him grinning happily as Norma, blissfully oblivious to the effect it must have on her daughter/ Mickey’s wife, Holly, toasts Hannah’s latest theatrical triumph to the enthusiastic approbation of all in attendance. Consequently, the two worlds of

Hannah and Her Sisters

almost, but don’t quite, converge in the final Thanksgiving scene. Allen obviously understood that dramatizing Mickey’s participation in this annual ceremony would create an image as incredible as that of Mickey mounting a crucifix on his apartment wall or dancing at airports in the garb of Hare Krishna. Even in a film as lushly affirmative in tone and surface as

Hannah and Her Sisters,

there are still some conversions the viewer, like Woody Allen, would simply never accept.