Read The Road to Freedom Online

Authors: Arthur C. Brooks

The Road to Freedom (3 page)

Welfare had two pernicious effects, according to Murray. First, the system effectively held people in miserable conditions, harming those it was supposed to help. This was immoral and had to stop. Second, by holding people in this condition, the system created dependency on the state, stripping people of the dignity that comes from earning their own way. Once again, this was immoral because it hurt the recipients themselves.

Such arguments were radical in the mid-1980s. It took more than ten yearsâas major policy reforms always tend to takeâbut the moral case for welfare reform ultimately won the day and was even embraced by a Democratic president. During the Clinton administration, legislation was crafted to reduce the extent to which people could become dependent on the system. It did so by imposing time limits on how long people could receive support and requiring them to work to receive benefits. Welfare reform was signed into law in 1996.

22

Welfare reform was a resounding success. According to the U.S. government, it helped to move 4.7 million Americans from welfare dependency to self-sufficiency within three years of enactment, and the welfare caseload declined by 54 percent between 1996 and 2004.

23

Even more importantly, there is evidence that it improved the lives of those who moved off welfare as a result. A new economic study using the General Social Survey shows that single mothersâdespite lost leisure time and increased stress from finding child care and performing household duties while workingâwere significantly happier about their lives after reforms led them into the workforce.

24

The point to remember here is this: Welfare reform was not passed when welfare became too expensive, but only when the moral case had been made that welfare was destroying the lives of the most vulnerable among us.

â¢

â¢

â¢

THIS BOOK IS

my attempt to make the moral case for free enterprise and then apply that case to the leading policy issues of our day. If you have always believed free enterprise is the best system for America and are looking for the right arguments to win the debate, you will find those arguments in this book. And if you're not so sure free enterprise is the best answer for America, then I hope I might persuade youâas I have been persuaded.

I did not grow up committed to the free enterprise systemârather the opposite, in fact. I was raised in Seattle, one of the most progressive cities in America, in a family of artists and academics. No one in my world voted for Ronald Reagan. I had no friends or family who worked in business. I believed what most everybody in my world assumed to be true: that capitalism was a bit of a sham to benefit rich people, and the best way to get a better, fairer country was to raise taxes, increase government services, and redistribute more income.

I am a believer in free enterprise today only because of the studies I pursued starting in my twenties. I didn't go to a fancy university; I didn't even make it to college until I was twenty-eight years old and, then, only by correspondence courses at night. In a way, I got lucky; I didn't have to fit into any progressive campus social life, or impress any radical professors. I just had a stack of books on economics and a lot of data about the real world to study after I came home from work each day.

As I began to question my old views, some around me reacted with alarm. At one point when I was around age thirty, my mother took me aside and said, “Arthur, I need you to tell me the truth. . . . Have you been voting for Republicans?”

In truth, there had been no Road-to-Damascus political conversion experience, just a slow realization that what I thought I

knewâabout how to help the poor, about what made America different from other nations, and what gave people the best set of opportunities for their livesâdidn't hold up to the evidence.

So I am not just a conservative ideologue or reflexive supporter of big business. In fact, I share the concerns of many on the left that freedom and opportunity are imperiled by corporate cronies, who inevitably are linked to the government through special deals and inside access. In this book, I'll argue that Washington's auto industry bailouts and its “Cash for Clunkers” program (handing out government grants to buy cars) are opposite sides of the same coin. Misbehavior on Wall Street was spawned by the predatory government-sponsored enterprises that started the housing crisis. Find me an opportunistic politician chumming the political waters with tax loopholes, and I'll show you a corporate shark.

I believe that if we want a better future, liberated from statism and corporate cronyism, the answer is the system that removes these shackles: free enterprise. In this book you will see why I have come to believe free enterprise is a beautiful, noble systemâso revolutionary in an imperfect worldâthat rewards aspiration instead of envy. It must be protected and strengthened for the sake of our self-realization, for a fairer society, and for the poor and vulnerableânot just because it is the best system to make us richer, but because it is the most moral system that allows us to flourish as people.

A S

YSTEM

T

HAT

A

LLOWS

U

S TO

E

ARN

O

UR

S

UCCESS

W

hen I was a college professor, I used to teach a course called “Social Entrepreneurship” for students studying nonprofit management. Every year, graduates would ask me for career advice. For many, the choice was between trying to start their own nonprofits and landing a safe job in the management of an existing nonprofit. I told them honestly that they were in for a lot of poverty if they started their own enterprise, but generally advised them to go for it anyway. I knew they would be much happier if they did.

Entrepreneurs of all types rate their well-being higher than any other professional group in America, according to years of polling by the Gallup organization.

1

Why are they so happy? It's not because they're making more money than everyone else; they aren't. According to the employment website

careerbuilder.com

in 2011, small business owners actually make 19 percent

less

money per year than government managers (and that's ignoring the huge benefits advantage that government workers have over

their private-sector counterparts).

2

Nor are entrepreneurs happy because they're working less than other people. Forty-nine percent of the self-employed clock more than forty-four hours per week, versus 39 percent of all workers.

3

So entrepreneurs work more and make less money than others. But they're happier people. What's their secret? In this chapter, I'll answer this question. It turns out to be the secret to everyone's happiness as well, regardless of whether or not they run their own businesses. I'll offer proof that money itself brings little joy to life, but that the free enterprise system brings what all people truly crave:

earned success.

That is what I believe the Founders meant by the pursuit of happiness.

THESE DAYS

, many scholars around the world are studying happiness. It may sound like a squishy topic, but it turns out there is a lot of good evidence on who is happy and who isn't.

We'll look at that in a minute. But first, let's discuss what people

think

will make them happy. At one point, I explored this question, albeit informally. I asked everybody I metâon planes, at parties, whereverâwhat was the one thing that would make them happier that very day. Some of the responses were funny; a few of them were unprintable.

A surprising number of people mentioned something about money. I say “surprising,” because we're all supposed to know that money doesn't buy happiness. Yet a lot of people, including those who are financially comfortable, feel that a little more money would improve their happiness. Is this true? The answer, according to the research on the subject, is not so simple.

One study on money and happiness examines different countries. Are citizens in rich countries happier than those in poorer

countries, on average? In 1974, University of Pennsylvania economist Richard Easterlin studied this question and concluded that people in rich countries are generally

not

happier than people in poorer ones.

4

The exceptions to this rule are desperately poor nations in areas like sub-Saharan Africa that are characterized by starvation and disease. But for countries above the level of subsistenceâand especially rich, developed countriesâmoney brings little extra happiness. This finding is known as the Easterlin Paradox.

5

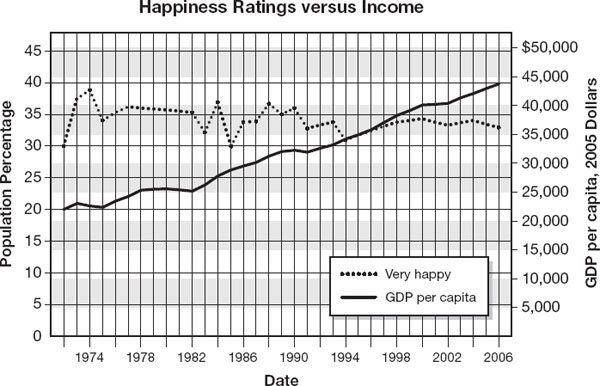

Looking at data for the United States over several decades, then, we shouldn't be too shocked to see that people have gotten a lot richer, but not much happier, on average. In 1972, about 30 percent of Americans told the General Social Survey they were very happy. The average American at that time earned about $25,000 a year, in 2004 dollars. By 2004, the average income had increased to $38,000 (a 50 percent increase in real income).

6

All income groups, from rich to poor, saw substantial income increases. Yet the percentage of very happy Americans stayed virtually unchanged, at 31 percent.

The story is the same in other developed countries. In Japan, real average income was six times higher in 1991 than in 1958. During the postâWorld War II period, Japan converted at historically unprecedented speed from a poor nation into one of the world's richest. Yet average Japanese happiness didn't change at all over this period.

7

Maybe the problem is that these increases in average income are too gradual to stimulate happiness. It makes sense to me that three percent income increases, year after year, wouldn't give people a big reason to say they are happier about their lives. But perhaps sudden, huge income increases would do the trick. After all, that's what people think when they imagine getting rich overnight.

Figure 2.1

. While average income in America has risen over the decades, average happiness has not. (Source: James A. Davis, Tom W. Smith, and Peter V. Marsden, General Social Surveys, 1972â2004 [Storrs, Conn.: The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut, 2004].)

Have you ever played the party game where people say what they would do if they won the lottery? The answers are usually predictable, but provide a bit of insight into each person's character and dreams. Some people say they'd travel more or change jobs; others say they would buy things. When men are trying to impress women, they sometimes say, “I'd start a foundation.” (Sure they would.)

Whatever they want to do with the money, people always say

good

things would result if they hit the lottery and that their lives would get better. I've never heard anybody say, “If I won the jackpot, I'd make some horrible life choices including marrying somebody who doesn't love me. Next, I'd buy a bunch of things I don't really want. Then, I'd start an ugly alcoholic downward spiral.”

But, in fact, the latter scenario is closer to what actually happens when people hit the jackpot. A study by researchers at the

University of Michigan looked at major lottery winners, people who won millions and millions of dollars all at once.

8

The researchers wanted to see how much happier the winners were after they had struck it rich.

The results were depressing. While the winners experienced an immediate happiness boost right after winning, it didn't last. Within a few months, their happiness levels receded to where they had been before winning. As time passed, they found they were actually worse off in happiness than before they had won. The novelty of buying new things wore off. Meanwhile, the small, simple things in life (such as talking to friends or going for a walk) were less pleasurable than they had been in the old days.

One reason money doesn't buy happiness is that people adapt to new economic circumstances incredibly quickly. Maybe you've noticed that you get the most enjoyment from a pay raise the day you find out about it, even more than when you get to spend it, and much more than you will a year after it has become a regular part of your paycheck. Economic gains and losses give pleasure or pain when they happen, but the effect rapidly wears off. People are excellent at perceiving changes to their surroundings or circumstances; they're not so good at sustaining any special sensation from the status quo.

Getting richer is like speeding up a treadmill: There's more activity, but you never get any closer to a goal. According to Adam Smith, a great believer in the benefits of people pursuing economic interests for personal satisfaction, “the mind of every man, in a longer or shorter time, returns to its natural and usual state of tranquility. In prosperity, after a certain time, it falls back to that state; in adversity, after a certain time, it rises up to it.”

9

Economists refer to the tendency to adapt as the “hedonic treadmill” and have demonstrated how it works in experiments.