The Thirteenth House (Twelve Houses) (2 page)

Read The Thirteenth House (Twelve Houses) Online

Authors: Sharon Shinn

For Debbie,

who knows the rest of the story

who knows the rest of the story

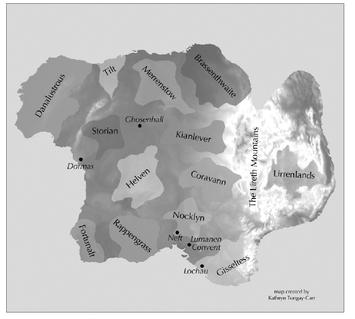

GILLENGARIA

CHAPTER

1

1

T

HE three men sat in the mansion’s elegantly appointed study and discussed their options. They had drawn their chairs close to the fire, because the room was huge and the spring night was chilled and drearily wet. The only true circle of comfort was within the warm glow of the leaping flames. They were all drinking port and relishing the well-being that came from the consumption of an excellent meal and the accomplishment of a difficult task.

HE three men sat in the mansion’s elegantly appointed study and discussed their options. They had drawn their chairs close to the fire, because the room was huge and the spring night was chilled and drearily wet. The only true circle of comfort was within the warm glow of the leaping flames. They were all drinking port and relishing the well-being that came from the consumption of an excellent meal and the accomplishment of a difficult task.

“We could kill him outright,” said the oldest of the men. He was tall, silver-haired, and dressed in very fine clothes. It was not his house, but his proprietary air would make an outsider think so. “That sends a strong message to the king.”

“I am not so fond of looking a man in the eyes and stabbing him in the heart,” one of the others grumbled. He was short, dark-haired, less fashionable, and a little fretful in his manner. He was the sort of man who would point out all the risks in any enterprise, even the ones least likely to bring the whole project down. “I say we hold on to him for a while.”

“There are ways to kill a man that do not involve violence,” said the elder. “Merely forgetting to feed him. Merely neglecting to give him a fire on a night such as this.”

“But those methods take time, which we have very little of,” objected the third one. He was balding and heavyset, even pudgy, the kind of man who would normally appear genial. But tonight there was a calculating expression on his face. Even by friendly firelight, a certain ruthlessness molded his features. “By now, his men will be back in Ghosenhall, telling tales of outlaws on the high road. Surely even such a casual king as Baryn will guess that his regent did not fall afoul of simple highwaymen.”

The elder turned his silver head to give the portly man a considering look. “Then you want him dead more immediately and with more intent?”

“If we kill him, no matter how, there will be consequences,” said the fretful one. “I know you say the servants here are hand-picked, but many a servant has betrayed his lord before this.”

“I vouch for the servants,” said the first man coldly. “There are only four in the whole place, all loyal to me.”

“Have they seen you commit murder before?” the other asked skeptically. “If not, I do not think you can be so sure of them.”

The elder man looked annoyed. “We must make a decision. The man is in our hands. The king will want him back. Do we trade him in return for some concessions? And thereby bring attention to ourselves and show for certain where our alliances lie? Or do we kill him and let his body be found and therefore send a different message to the king? ‘We are readying ourselves for war. We distrust you, and your royal house, and the paltry counselors you have installed to guide your daughter. You cannot mollify us by any measures.’ ”

The other two murmured approval at this stirring speech, and the elder man leaned back in his chair to sip from his glass. “Yes, but what if the king doesn’t interpret our message just how we wish?” asked the short man after thinking it over. “What if he sees

treason

, not an honest cry for change? For we play a tricky game here. We are still very early in the game. Anything could go awry—and here we are in Tilt lands, on Tilt property. Marlord Gregory will be blamed for any cold body found lying about in Tilt fields.”

treason

, not an honest cry for change? For we play a tricky game here. We are still very early in the game. Anything could go awry—and here we are in Tilt lands, on Tilt property. Marlord Gregory will be blamed for any cold body found lying about in Tilt fields.”

“Marlord Gregory has been gracious enough to lend us his estate,” said the heavy man in a purring voice. “Surely he cannot cavil at the uses to which we put his house?”

The short man was shaking his head. Someone who was looking closely might have noticed, even in the dark room, that he was wearing an aquamarine stud on the lapel of his jacket. A Tilt man, wearing the Tilt colors. “Gregory is very clever. He does not see how the wind blows, not yet, and he has not shown even his most loyal vassals what cards he holds. He dislikes the king—yes, and this ridiculous regent set up to rule over us if something happens to Baryn—but he is not so sure he wants to usher in the age of Gisseltess rule, either.”

The silver-haired man gave a growl of annoyance. “Trust a Tilt to merely want to stir the pot without wanting to taste the stew,” he said in a voice holding some contempt. “Gregory cannot have it both ways. Either he works for revolution, or he does not. And revolution, my friend, is dressed in the garb of Gisseltess and wears the falcon clipped to its cloak.” Someone looking closely at

him

would have noticed that very same falcon embroidered on his vest. A man of Gisseltess.

him

would have noticed that very same falcon embroidered on his vest. A man of Gisseltess.

The portly man gave a light laugh. “Revolution wears more motley colors than that,” he said. “The maroon of Rappengrass, the scarlet of Danalustrous—you can find them all, if you look hard enough.” Though he himself wore no such identifying marks; it would have been hard to guess which House he represented—or plotted against. He continued. “All of us want the same things—the recognition and prestige that are due to us, which have not come our way under this king.”

“And who’s to say it will come under Halchon Gisseltess?” demanded the Tilt man. “Eh? If he steals the throne from under Baryn’s nose? Who’s to say he will turn over any land or power to the lords of the Thirteenth House?”

“So he will call together the nobles of the Thirteenth House,” the portly man said in a mocking voice. “He will say, ‘Too long you have been regarded as the “lesser lords.” Too long have you been vassals to the marlords of the Twelve Houses who consider themselves your superiors in every way! Let us redistribute the property and give you a higher place in society.’ ”

“He swears he will reward us all with lands and titles of our own,” said the Gisseltess man. “If we help him win the throne.”

“I have been promised many things by marlords in the past,” said the Tilt man in a bitter voice. “Many of those promises have been forgotten.”

“And many have been remembered,” the older man said sharply. “Halchon has honor.”

“As do all men who depose their king,” replied the heavy fellow in a sardonic tone.

The older man spread his hands. “Late to be having doubts now that Romar Brendyn is locked in the attic of this house!” he exclaimed. “Whether we kill him now or we trade him back to his king, we have committed ourselves to civil dissent. And I tell you plainly, if we do

not

kill him, we have less room to maneuver, for we will have shown our hands. We will have stated in the clearest possible fashion that we are in opposition to our king. Whereas if he is dead . . . well, who knows whose hand may have done him in? We might be entirely guiltless. No one will be able to point at us and say, ‘You did this thing.’ We might change our minds altogether about which side we choose in this war, and no one will be the wiser.”

not

kill him, we have less room to maneuver, for we will have shown our hands. We will have stated in the clearest possible fashion that we are in opposition to our king. Whereas if he is dead . . . well, who knows whose hand may have done him in? We might be entirely guiltless. No one will be able to point at us and say, ‘You did this thing.’ We might change our minds altogether about which side we choose in this war, and no one will be the wiser.”

“You want to kill him then,” said the Tilt man. “You see no choice.”

“I see many choices,” said the Gisseltess man, “but I admit that I would like to see him dead.”

They both looked at the heavyset man, the one who had been so very cagey up till now, careful what he committed himself to either in writing or in words. Yet he had been the one to supply the funds and the manpower; he was in it up to his neck, no matter what the outcome. He was silent a long moment, as if debating, as if considering for the very first time which of the possible outcomes he preferred and what consequences they might set in motion. At last, his shoulders seeming both bulky and weightless in the shadows thrown by the firelight, he gave a shrug.

“Well, I don’t suppose—” he began, but his voice was interrupted by a furious pounding that seemed to come from the front of the house.

The three of them looked at each other with wide-eyed dismay. “Was that the door?” said the Gisseltess man in disbelief. “Has someone come calling—at this place, at this time, on such a night?” They had chosen the mansion to conduct their business for a variety of reasons, one of them being its remote inaccessibility. Only someone familiar with the rocky northern stretches of Tilt would have any idea where the house lay, or know which of marlord Gregory’s many vassals was its landlord.

“Perhaps it was only thunder, rattling the casements,” offered the heavyset man.

The Gisseltess man stalked to the window and threw back the heavy curtain. Nothing could be seen but a liquid blackness, midnight washed clean by heavy rain. “I can tell nothing from here.”

“Perhaps—”

But there it was again, a hailstorm of blows on wood, and now the sound of upraised voices crying out for admittance. “Will the servants answer?” the Tilt man asked in a voice barely above a whisper, as if those standing outside below could hear him if he spoke aloud.

There was more rough knocking on the door. “They will have to,” the Gisseltess man said with some grimness. “Or I fear our callers will bring the house down.”

The three of them were on their feet by now, and they moved silently to their own door, closed firmly on the rest of the house, and held themselves still to listen. Voices in the hall, some calm, some excited—no doubt the admirable butler greeting these most unwelcome visitors. The three men waited, unmoving, barely breathing, attempting to catch a word or a sentence that would explain how these travelers had so disastrously come calling. Within minutes, the voices died down to a murmur and then were gone entirely.

“He’s escorted them to some parlor or another,” the Gisseltess man said. “He’s admitting them to the house.”

“But why—”

“He must have his reasons.”

Indeed, a few moments later, they could hear the measured sounds of the butler’s footsteps ascending the stairs. Before he could knock on the door, the older man jerked it open.

“Well?” he demanded. “Who has arrived? Surely you realize this is not a house that can afford to take in chance-met travelers.”

The butler nodded with complete tranquillity. He looked to be quite ancient, his face lined and wrinkled, his gray hair so thin around his face it was almost only a memory of hair. But his eyes were imperturbable and hinted at so many secrets known that he could not begin to recount them all. “These were not the sorts of people who could be turned out into the weather,” he said—adding, after a pause so long it might almost be considered insolent, “my lord.”

The fretful Tilt man hissed out a long-held breath. “Who, then? Who are they?”

The butler addressed the older man as if the other had not spoken. “One is a servant girl, two are guards. But the head of their party is a woman who is clearly highborn. Twelfth House. Serramarra, I believe. She has fallen ill on the road and looks to be in a high fever, which is why they have sought shelter here.”

The Gisseltess man regarded the butler steadily. “Did you recognize her or are you just guessing?”

The butler chose not to answer directly. “She has long golden hair and exceptionally fine features,” he said. “Her clothes were quite expensive. I saw the crest of Danalustrous on her cloak and on her servant’s luggage.”

Another hiss from the short, anxious man. “Kirra Danalustrous,” he said bitterly. “Malcolm’s shiftling daughter.”

The butler nodded. “So I believe. My lord.”

There was a moment’s silence while the Gisseltess man clearly tried to decide what to do next. “What have you done with her? And her retinue?”

“At the moment they are in the small parlor. My lord. I have asked the housekeeper to make up a room for them on the second floor. In the other wing. Her servant girl is quite affected and refuses to leave her side for even a moment. Her guards are—”

Other books

My Lady of Cleves: Anne of Cleves by Margaret Campbell Barnes

Racing for Freedom by Bec Botefuhr

Lucidity by Raine Weaver

The Dog Said Bow-Wow by Michael Swanwick

Wrong Alien (TerraMates Book 6) by Lisa Lace

Caversham's Bride (The Caversham Chronicles - Book One) by Raven, Sandy

Murder in Pug's Parlour by Myers, Amy

Eastern Approaches by Fitzroy MacLean

Consensus Breaking (The Auran Chronicles Book 2) by M. S. Dobing

Forty Signs of Rain by Kim Stanley Robinson