The Triumph of Seeds (33 page)

Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

Evolution behaves much like a gardener, saving only the most successful experiments. And there is nothing necessarily inviolate about the triumph of seeds. Just as the spore plants yielded their dominance, so might seeds eventually give way to something new. In fact, this process may already be underway. With over 26,000 recognized species, orchids make up the most diverse and highly evolved plant family on earth. Yet their seeds are hardly seeds at all. Break open an orchid pod and the seeds puff out like dust, microscopic blips that essentially lack seed coats, defensive chemicals, or any discernable nutrition. They are still baby plants, but in Carol Baskin’s analogy, they don’t have the box or the lunch. In fact, they can only germinate and grow if they land in soil that contains just the right kind of symbiotic fungi. As such, orchid seeds have very little to offer people—no fuels, fruits, foods, or fibers, no stimulants or useful drugs. Only one species out of all those thousands produces a seed product with any commercial value—vanilla. If orchids didn’t have beautiful flowers, we would hardly be aware of them at all.

Paleobotanists like Bill DiMichele take the long view on plant evolution, watching traits, species, and whole groups wax and wane through the fossil record. Bill doesn’t think the reign of seeds will end anytime soon. “Orchids are freeloaders,” he assured me. In addition to their reliance on fungi, most species are epiphytes, using other plants for support and structure. And their attractive flowers rarely contain nectar or accessible pollen, a system of trickery that

would fall apart if other plants didn’t offer reliable rewards. Still, if nearly one out of every ten species in the global flora is an orchid, it’s hard not to believe that they’re on to something. The success of using simple, dust-like seeds reminds us that complexity is a symptom of evolution, not a consequence. All the elaborate and remarkable features found in seeds—from nourishment to endurance to protection—will persist only so long as they benefit future generations. Seeds embody the biology of passing things down. In a sense, that is also the root of their deep cultural significance. Seeds give us a tangible connection from past to future, a reminder of human relationships as well as the natural rhythms of season and soil.

Last fall, Noah and I collected the seeds of bellflower and pink mallow from my mother’s overgrown flower garden. I brought them home to pep up a patch of bare ground in front of the Raccoon Shack. On an afternoon in early spring, we shoveled up the soil of our small plot, pulled a few weeds, and brought out the seeds. Noah inspected them closely, commenting on the blackish nubs of mallow in their webbed pouches, and the tiny bellflowers, like flecks of golden dust. When it came time to plant, he threw exuberant fistfuls across the turned earth, and then added something of his own—four kernels of popcorn carefully saved from a snack earlier in the day.

As luck would have it, we chose a perfect moment for planting. Steady rain that afternoon watered in the seeds and then the skies cleared, giving us days and days of sunshine. The mallows germinated quickly, surging upward with wisps of seed coat still clinging to their new leaves. Two weeks have passed, and as I write these lines I can hear Eliza outside my office window, pointing out the baby plants to Noah. “There’s another

malva

,” she tells him, using the botanical name. “See it?”

He answers yes, and later shows the seedlings proudly to me—brave green specks brightening a backdrop of dirt. By the time this book goes to print, they will be in bloom.

*

The crux of the matter is simple division. Plants with an even number of chromosomes can easily give half that allotment to their pollen or sperm cells, which then unite to form a seed. Crossing diploid and tetraploid plants, however, produces individuals with three sets of chromosomes, a number that cannot be divided evenly. Triploid plants may be healthy, but they are sterile, unable to make viable pollen or eggs, and therefore unable to form seeds.

T

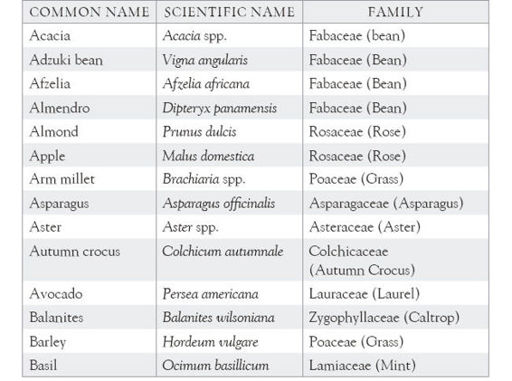

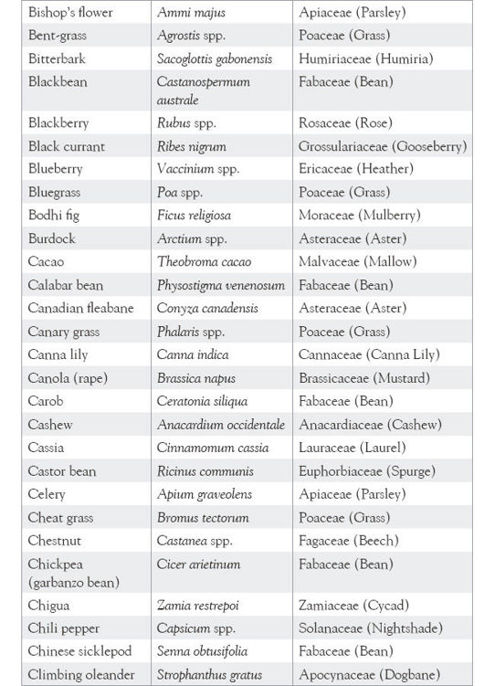

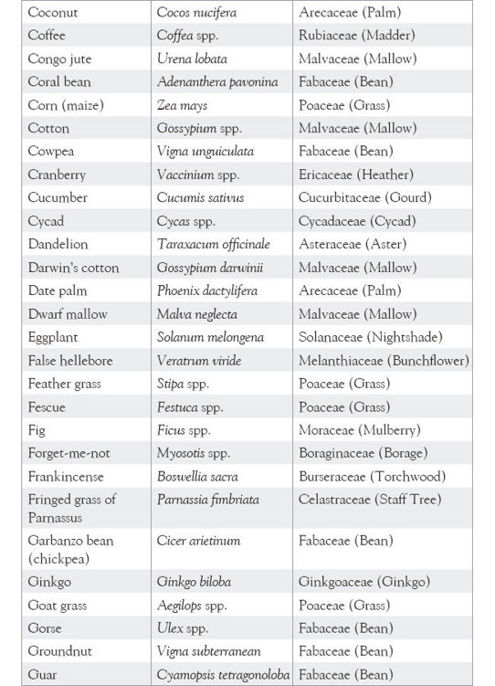

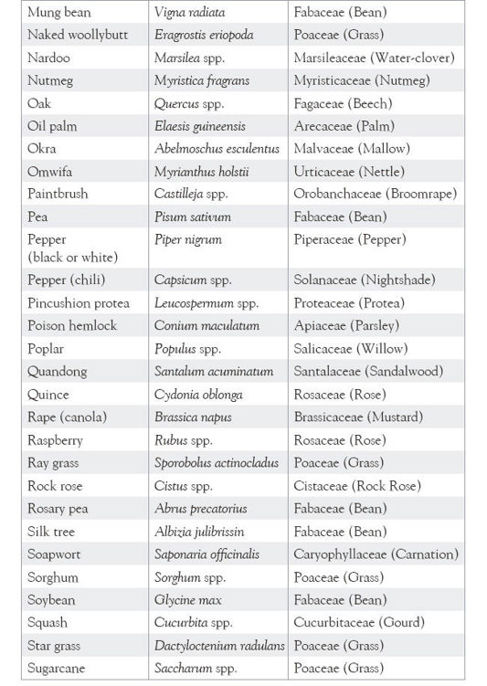

he following list includes common, scientific, and family names for all plant species mentioned in the text.

A

portion of the proceeds from this book will be donated to help preserve the diversity of seeds from both wild and cultivated species. To further these efforts directly, consider making a donation to one of the following organizations.

Seed Savers Exchange

3094 North Winn Road

Decorah, IA 52101, USA

Phone: (563) 382–5990

www.seedsavers.org

Organic Seed Alliance

PO Box 772

Port Townsend, WA 98368, USA

Phone: (360) 385–7192

www.seedalliance.org

Global Crop Diversity Trust

Platz Der Vereinten Nationen 7

53113 Bonn, Germany

Phone: +49 (0) 228 85427 122

www.croptrust.org