100 Most Infamous Criminals (7 page)

Read 100 Most Infamous Criminals Online

Authors: Jo Durden Smith

Victor Lustig sold the Eiffel Tower twice!

Chizuo Matsumoto (aka Shoko Asahara)

I

n the 1980s, a partially blind Japanese masseur called Chizuo Matsumoto (aka Shoko Asahara) claimed to have travelled to the Himalayas and to have achieved nirvana there – he said he could now levitate and even walk through walls. A group of believers gathered around him into an organization called AUM Supreme Truth and in spring 1989 they applied to the Tokyo Municipal Government for registration as a religion.

The bureaucrats had their doubts. For Asahara, as he preferred to call himself, had a police record for fraud and assault; and there were already complaints that AUM was abducting children and brainwashing them against their parents. In August, though, they caved in after demonstrations by AUM members, giving it not only tax-exempt status, but also the right to own property and to remain free of state and any other interference.

Less than three months later, a young human rights lawyer who had been battling the cult on behalf of worried parents vanished into thin air, along with his wife and infant son. It later transpired that a television company had shown an interview with the lawyer to senior AUM members before its transmission, but it hadn’t bothered to tell the lawyer this. Nor did it bother to tell the police either, after the lawyer’s disappearance.

In the period between 1989 and 1995, AUM hit the news in a variety of ways, mostly as a public nuisance. But the locals who protested its setting up of yoga schools and retreats in remote rural areas didn’t know the half of it. For during these years AUM – which attracted many middle-class professionals – began using them to stockpile the raw materials used in making nerve agents: sarin and its even more deadly cousin VX. Its members tried to produce conventional weapons, AK-47s, but they also travelled deep into research on botulism and a plasmaray gun. When in 1993 neighbours complained of a foul smell coming from an AUM building in central Tokyo, the police took no action. But then they weren’t to know that scientists there were doing their best to cultivate anthrax.

Then on the night of June 27th 1994, in the city of Matsumoto 150 miles west of Tokyo, a man called the police complaining of noxious fumes, and subsequently became so ill he had to be rushed to hospital. Two hundred others became ill and seven died. Twelve days later, this time in Kamikuishikimura, a rural village three hundred miles north of Tokyo, the same symptoms – chest pains, nausea, eye problems – reappeared in dozens of victims. And though this time no one died, the two attacks had something sinister in common. For the Matsumoto deaths, it was discovered, had been caused by sarin, hitherto unknown in Japan; and the village casualties by a by-product created in its manufacture.

The villagers were convinced that the gas had come from an AUM building nearby and by the beginning of 1995, the newspapers – if not the police – had begun to put two and two together. One paper reported that traces of sarin had been found in soil samples near another AUM retreat; another explained the attack on Matsumoto, for three judges who were to rule on a lawsuit brought against AUM lived in a building there next to a company dormitory where most of the casualties had occurred.

Still the police took no action. Nor did they move when in February a notary, a well known opponent of the sect, was abducted in broad daylight in Tokyo by a van that could be traced to AUM. In early March, passengers on a Yokohama commuter train were rushed to hospital complaining of eye irritation and vomiting; and ten days later the method in which they’d probably been attacked was found. Three attaché cases – containing a liquid, a vent, a battery and small motorized fans – were discovered dumped at a Tokyo station.

Perhaps forewarned of a coming police raid, AUM took preemptive action. At the height of the morning rush hour on March 25th, cult members released sarin on three subway lines that converged near National Police headquarters. Twelve died and over five thousand were injured. There was panic all over Japan. But, though the police did raid some AUM facilities the following day, they still failed to find Asahara and his inner circle. The price they paid was high. For on March 30th a National Police superintendent was shot outside his apartment by an attacker who got away on a bicycle. A parcel bomb was sent to the governor of Tokyo; cyanide bombs were found and defused in the subway system; and when a senior AUM figure was finally arrested, he was promptly assassinated, like Lee Harvey Oswald.

Through all this, Asahara and a number of his ministers were in almost daily touch with selected press. In fact he wasn’t arrested, hiding out in a steel-lined room at AUM’s compound at Kamikuishikimura, until almost two months after the Tokyo attack. And it was only very slowly, even then, that his motives and the extent of his crimes were unravelled.

The ex-masseur had started AUM Supreme Truth, it seems, for the money he could make and he early recruited members from another sect who knew the religion business. But then he’d become infected by his own propaganda and when sect members ran in national elections in 1990 – and lost in a big way – he decided to bring down the government in preparation for a final Armageddon that would take place in 1997. Everything he undertook from then on was bent to this single purpose. In an atmosphere of obsessive secrecy, he organized bizarre initiation rituals and assassinated or abducted anyone who stood in his way. He demanded that members give up their worldly goods to him and had them killed if they refused. He operated prostitution clubs, made deals with drug syndicates, and instigated break-ins at government research laboratories. . .

The full extent of his crimes is still not yet known. For the trials and appeals of both Asahara and his high officers continues. Meanwhile, so does his cult – under a new name Aleph. It’s still remarkably popular.

Jacques Mesrine

P

resident Giscard d’Estaing regarded the failure to catch Jacques Mesrine as a national disgrace. Much of the rest of the population were delighted. For they sneakingly saw Mesrine as a combination of D’Artagnan, Robin Hood and Errol Flynn: a glorious example of France’s daring and ingenuity. True, he might have killed a few times – and that was regrettable. But his wit! His escapes! His nerve! Besides, he was the most famous criminal in the world – and he was French! When he finally died in a police ambush in Paris in 1979, the police may have hugged each other and danced in the street. But there was something in the heart of every true Frenchman that mourned.

Mesrine was born in Paris in 1937 – and from his earliest years he seems to have been in love with danger. As a schoolboy he was laid-back, fond of argument and good with his fists; as a teenager, he hung out with other tearaways and played hookey to go joyriding. For a while he tried marriage, but he couldn’t settle down, and when he was conscripted into the army he specifically asked to be sent to Algeria, where the French army was fighting a ‘dirty war’ against Muslim anti-colonialists.

He was demobbed with a Military Cross for bravery. But life as a civilian – after seeing action – seemed to bore him. He committed his first burglary, on the flat of a wealthy businessman, in 1959 – and it bore all the hallmarks of what was to come. When a drill snapped as he was boring his way into the safe, he simply left, broke into a hardware store for more and came back to finish the job. He escaped with millions of francs.

His reputation rapidly spread in the underworld – and among the police. In 1962 he was arrested on his way to a bank job and sentenced to three years in prison. Out a year later, he tried to go straight: he got married again and apprenticed himself to an architect. But after showing real aptitude, he was made redundant, and he went back to the high-wire daring and near escapes of crime. Within four years he was the most wanted thief in France; the police were infuriated by his audacious antics. So, after one last major job at a hotel in Switzerland, he took himself off with his latest girlfriend, Jeanne Schneider, to Canada.

They were soon employed, as chauffeur and housekeeper, by a Montreal millionaire. But after rows with other staff, they were sacked. So Mesrine and Jeanne simply kidnapped the millionaire and held him for $200,000 ransom. Unfortunately they were caught and charged both with the kidnap and with the murder of a rich widow they’d befriended in the small town of Percé nearby.

From the beginning Mesrine was outraged: he insisted they’d had nothing to do with the widow’s murder. (They were both eventually acquitted.) But he engineered his and Jeanne’s escape from the Percé jail; and after they were caught again, and tried and sentenced for the kidnap, he organized another spectacular escape from the ‘escape-proof’ St. Vincent de Paul prison at Laval. (He later tried to go back to free the rest of the prisoners, but got into a gunfight with the police along the way.)

The escape made Mesrine a national celebrity in Canada, but his reputation darkened after he shot to death two forest rangers who’d recognized him. So finally, after some extraordinarily insouciant bank hold-ups – he robbed one bank twice because a cashier had scowled at him on the way out the first time – he decided to take the money, and a new mistress, to Venezuela.

In 1973, though, Mesrine was back in France and up to his old tricks. After a string of armed robberies, he was finally arrested. But he again escaped, this time from the Palais de Justice in Compiègne. By now, he was deep into his gentleman-thief, Robin-Hood role. When, during a bank robbery, a young woman cashier accidentally pushed the alarm button, he said,

‘Don’t worry, my dear. I like to work to music,’

and calmly went on gathering the money. On another occasion, when his father was in hospital, dying of cancer and closely watched, he simply dressed up as a doctor – with white coat and stethoscope – and went to visit him.

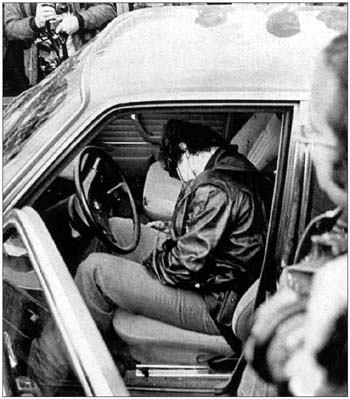

Mesrine was eventually shot dead by Parisian police

When he was finally arrested and then held in Santé Prison, he whiled away the time writing his autobiography. Then, when his case, after three and a half years, came to trial, he gave a demonstration in court that was to seal his reputation. After saying that it was easy enough to buy a key for any pair of handcuffs, he simply took out a key from a match-box hidden in the knot of his tie and opened his own handcuffs.

A year later, after being sentenced to twenty years, he escaped yet again, and continued his bizarre adventures. He walked into a Deauville police station, saying he was an inspector from the Gaming Squad and asked to see the duty inspector. When told he was out, he took himself off and that night robbed a Deauville casino. He also invaded the house of a bank official who’d testified against him at his trial, and forced him to withdraw half a million francs from his own bank. He gave an interview to

Paris Match

, the first of several he gave to journalists; and he even then attempted to kidnap the judge who’d tried him. Though this went badly wrong, he escaped by telling the police whom he met on their way up the stairs: ‘Quick, quick, Mesrine’s up there.’

By the time he was finally caught up with, he was living with a girlfriend in a luxury apartment in Paris; and the police were in no mood to compromise. They staked out the apartment, and then when the couple came out and climbed into his BMW, they were soon hemmed in by two lorries. Unable to move, he was then shot – in effect, executed. The police thereupon kissed each other and danced in the street – and President Giscard d’Estaing was immediately informed of their triumph.

Dr. Marcel Pétiot

D

r. Marcel Pétiot’s crimes, among the most grisly in European history, were motivated by nothing but greed. As he walked to the guillotine in Paris on May 26th 1946, he is said to have remarked:

‘When one sets out on a voyage, one takes all one’s luggage with one.’

This was not a privilege given to any of his more than sixty victims. For at his trial two months before, the jury had been shown forty-seven suitcases that belonged to the men and women he’d murdered – containing over 1500 items of their clothing. All had been found at his death house on the rue Le Sueur.