1491 (27 page)

Contact with Indians caused Europeans considerably more consternation. Columbus went to his grave convinced that he had landed on the shores of Asia, near India. The inhabitants of this previously unseen land were therefore Asians—hence the unfortunate name “Indians.” As his successors discovered that the Americas were not part of Asia, Indians became a dire anthropogonical problem. According to Genesis, all human beings and animals perished in the Flood except those on Noah’s ark, which landed “upon the mountains of Ararat,” thought to be in eastern Turkey. How, then, was it possible for humans and animals to have crossed the immense Pacific? Did the existence of Indians negate the Bible, and Christianity with it?

Among the first to grapple directly with this question was the Jesuit educator José de Acosta, who spent a quarter century in New Spain. Any explanation of Indians’ origins, he wrote in 1590, “cannot contradict Holy Writ, which clearly teaches that all men descend from Adam.” Because Adam had lived in the Middle East, Acosta was “forced” to conclude “that the men of the Indies traveled there from Europe or Asia.” For this to be possible, the Americas and Asia “must join somewhere.”

If this is true, as indeed it appears to me to be,…we would have to say that

they crossed not by sailing on the sea, but by walking on land.

And they followed this way quite unthinkingly, changing places and lands little by little, with some of them settling in the lands already discovered and others seeking new ones. [Emphasis added]

Acosta’s hypothesis was in basic form widely accepted for centuries. For his successors, in fact, the main task was not to discover whether Indians’ ancestors had walked over from Eurasia, but which Europeans or Asians had done the walking. Enthusiasts proposed a dozen groups as the ancestral stock: Phoenicians, Basques, Chinese, Scythians, Romans, Africans, “Hindoos,” ancient Greeks, ancient Assyrians, ancient Egyptians, the inhabitants of Atlantis, even straying bands of Welsh. But the most widely accepted candidates were the Lost Tribes of Israel.

The story of the Lost Tribes is revealed mainly in the Second Book of Kings of the Old Testament and the apocryphal Second (or Fourth, depending on the type of Bible) Book of Esdras. At that time, according to scripture, the Hebrew tribes had split into two adjacent confederations, the southern kingdom of Judah, with its capital in Jerusalem, and the northern kingdom of Israel, with its capital in Samaria. After the southern tribes took to behaving sinfully, divine retribution came in the form of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser V, who overran Israel and exiled its ten constituent tribes to Mesopotamia (today’s Syria and Iraq). Now repenting of their wickedness, the Bible explains, the tribes resolved to “go to a distant land never yet inhabited by man, and there at last to be obedient to their laws.” True to their word, they walked away and were never seen again.

Because the Book of Ezekiel prophesizes that in the final days God “will take the children of Israel from among the heathen…and bring them into their own land,” Christian scholars believed that the Israelites’ descendants—Ezekiel’s “children of Israel”—must still be living in some remote place, waiting to be taken back to their homeland. Identifying Indians as these “lost tribes” solved two puzzles at once: where the Israelites had gone, and the origins of Native Americans.

Acosta weighed the Indians-as-Jews theory but eventually dismissed it because Indians were not circumcised. Besides, he blithely explained, Jews were cowardly and greedy, and Indians were not. Others did not find his refutation convincing. The Lost Tribes theory was endorsed by authorities from Bartolomé de Las Casas to William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania, and the famed minister Cotton Mather. (In a variant, the Book of Mormon argued that some Indians were descended from Israelites though not necessarily the Lost Tribes.) In 1650 James Ussher, archbishop of Armagh, calculated from Old Testament genealogical data that God created the universe on Sunday, October 23, 4004

B.C.

So august was Ussher’s reputation, wrote historian Andrew Dickson White, that “his dates were inserted in the margins of the authorized version of the English Bible, and were soon practically regarded as equally inspired with the sacred text itself.” According to Ussher’s chronology, the Lost Tribes left Israel in 721

B.C.

Presumably they began walking to the Americas soon thereafter. Even allowing for a slow passage, the Israelites must have arrived by around 500

B.C.

When Columbus landed, the Americas therefore had been settled for barely two thousand years.

The Lost Tribes theory held sway until the nineteenth century, when it was challenged by events. As Lund had in Brazil, British scientists discovered some strange-looking human skeletons jumbled up with the skeletons of extinct Pleistocene mammals. The find, quickly duplicated in France, caused a sensation. To supporters of Darwin’s recently published theory of evolution, the find proved that the ancestors of modern humans had lived during the Ice Ages, tens or hundreds of thousands of years ago. Others attacked this conclusion, and the skeletons became one of the

casus belli

of the evolution wars. Indirectly, the discovery also stimulated argument about the settlement of the Americas. Evolutionists believed that the Eastern and Western Hemispheres had developed in concert. If early humans had inhabited Europe during the Ice Ages, they must also have lived in the Americas at the same time. Indians must therefore have arrived before 500

B.C.

Ussher’s chronology and the Lost Tribes scenario were wrong.

The nineteenth century was the heyday of amateur science. In the United States as in Europe, many of Darwin’s most ardent backers were successful tradespeople whose hobby was butterfly or beetle collecting. When these amateurs heard that the ancestors of Indians must have come to the Americas thousands of years ago, a surprising number of them decided to hunt for the evidence that would prove it.

“BLIND LEADERS OF THE BLIND”

In 1872 one such seeker—Charles Abbott, a New Jersey physician—found stone arrowheads, scrapers, and axheads on his farm in the Delaware Valley. Because the artifacts were crudely made, Abbott believed that they must have been fashioned not by historical Indians but by some earlier, “ruder” group, modern Indians’ long-ago ancestors. He consulted a Harvard geologist, who told him that the gravel around the finds was ten thousand years old, which Abbott regarded as proof that Pleistocene Man had lived in New Jersey at least that far in the past. Indeed, he argued, Pleistocene Man had lived in New Jersey for so many millennia that he had probably

evolved

there. If modern Indians

had

migrated from Asia, Abbott said, they must have “driven away” these original inhabitants. Egged on by his proselytizing, other weekend bone hunters soon found similar sites with similar crude artifacts. By 1890 amateur scientists claimed to have found traces of Pleistocene Americans in New Jersey, Indiana, Ohio, and the suburbs of Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

Unsurprisingly, Christian leaders rejected Abbott’s claims, which (to repeat) contradicted both Ussher’s chronology and the theologically convenient Lost Tribes theory. More puzzling, at least to contemporary eyes, was the equally vehement objections voiced by professional archaeologists and anthropologists, especially those at the Smithsonian Institution, which had established a Bureau of American Ethnology in 1879. According to David J. Meltzer, a Southern Methodist University archaeologist who has written extensively about the history of his field, the bureau’s founders were determined to set the new disciplines on a proper scientific footing. Among other things, this meant rooting out pseudoscience. The bureau dispatched William Henry Holmes to scrutinize the case for Pleistocene proto-Indians.

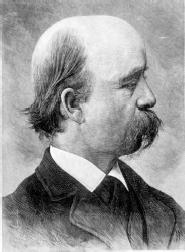

C. C. Abbott

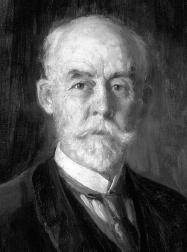

William Henry Holmes

Holmes was a rigorous, orderly man with, Meltzer told me, “no sense of humor whatsoever.” Although Holmes in no way believed that Indians were descended from the Lost Tribes, he was also unwilling to believe that Indians or anyone else had inhabited the Americas as far back as the Ice Ages. His determined skepticism on this issue is hard to fathom. True, many of the ancient skeletons in Europe were strikingly different from those of contemporary humans—in fact, they were Neanderthals, a different subspecies or species from modern humans—whereas all the Indian skeletons that archaeologists had seen thus far looked anatomically modern. But why did this lead Holmes to assume that Indians must have migrated to the Americas in the recent past, a view springing from biblical chronology? Underlying his actions may have been bureau researchers’ distaste for “relic hunters” like Abbott, whom they viewed as publicity-seeking quacks.

Holmes methodically inspected half a dozen purported Ice Age sites, including Abbott’s farm. In each case, he dismissed the “ancient artifacts” as much more recent—the broken pieces and cast-asides of Indian workshops from the colonial era. In Holmes’s sardonic summary, “Two hundred years of aboriginal misfortune and Quaker inattention and neglect”—this was a shot at Abbott, a Quaker—had transformed ordinary refuse that was at most a few centuries old into a “scheme of cultural evolution that spans ten thousand years.”

The Bureau of American Ethnology worked closely with the United States Geological Survey, an independent federal agency founded at the same time. Like Holmes, Geological Survey geologist W. J. McGee believed it was his duty to protect the temple of Science from profanation by incompetent and overimaginative amateurs. Anthropology, he lamented, “is particularly attractive to humankind, and for this reason the untrained are constantly venturing upon its purlieus; and since each heedless adventurer leads a rabble of followers, it behooves those who have at heart the good of the science…to bell the blind leaders of the blind.”

To McGee, one of the worst of these “heedless adventurers” was Abbott, whose devotion to his purported Pleistocene Indians seemed to McGee to exemplify the worst kind of fanaticism. Abbott’s medical practice collapsed because patients disliked his touchy disposition and crackpot sermons about ancient spear points. Forced to work as a clerk in Trenton, New Jersey, a town he loathed, he hunted for evidence of Pleistocene Indians during weekends on his farmstead. (In truth, the Abbott farm

had

a lot of artifacts; it is now an official National Historic Landmark.) Bitterly resenting his marginal position in the research world, he besieged scientific journals with angry denunciations of Holmes and McGee, explanations of his own theories, and investigations into the intelligence of fish (“that this class of animals is more ‘knowing’ than is generally believed is, I hold, unquestionable”), birds (“a high degree of intelligence”), and snakes (“neither among the scanty early references to the serpents found in New Jersey, nor in more recent herpetological literature, are there to be found statements that bear directly upon the subject of the intelligence of snakes”).

Unsurprisingly, Abbott detested William Henry Holmes, W. J. McGee, and the “scientific men of Washington” who were conspiring against the truth. “The stones are inspected,” he wrote in one of the few doggerel poems ever published in Science,

And Holmes cries, “rejected,

They’re nothing but Indian chips.”

He glanced at the ground,

Truth, fancied he found,

And homeward to Washington skips….

So dear W.J.,

There is no more to say,

Because you’ll never agree

That anything’s truth,

But what issues, forsooth,

From Holmes or the brain of McGee.