172 Hours on the Moon (2 page)

Read 172 Hours on the Moon Online

Authors: Johan Harstad

“That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard,” Mia Nomeland said, giving her parents an unenthusiastic look. “No way.”

“But Mia, honey. It’s an amazing opportunity, don’t you think?”

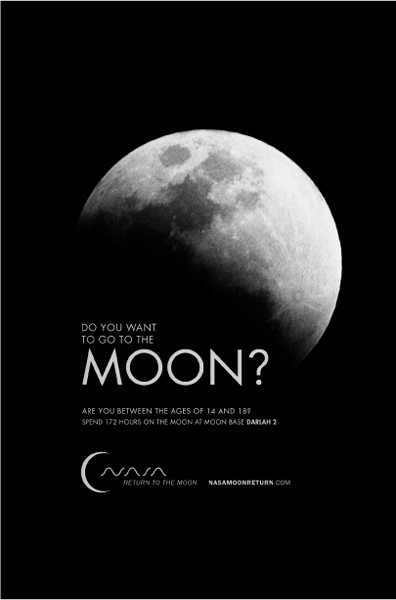

Her parents were sitting side by side on the sofa, as if glued together, with the ad they had clipped out of the newspaper

lying on the coffee table in front of them. Every last corner of the world had already had a chance to see some version of

it. The campaign had been running for weeks on TV, the radio, the Internet, and in the papers, and the name NASA was on its

way to becoming as well known around the globe as Coca-Cola or McDonald’s.

“An opportunity for what? To make a fool of myself?”

“Won’t you even consider it?” her mother tried. “The deadline isn’t for a month, you know.”

“No! I don’t want to consider it. There’s nothing for me to do up there. There’s something for me to do absolutely everywhere

except

on the moon.”

“If it were me, I would have applied on the spot,” her mother said.

“Well, I’m sure my friends and I are all very glad that you’re not me.”

“Mia!”

“Fine, sorry. It’s just that I … I don’t

care

. Is that so hard for you to understand? You guys are always telling me that the world is full of opportunities and that you

have to choose some and let others pass you by. And that there are enough opportunities to last a lifetime and then some.

Right, Dad?”

Her dad mumbled some sort of response and looked the other way.

Her mother sighed. “I’ll leave the ad over here on the piano for a while, in case you change your mind.”

It’s always like this

, Mia thought, leaving the living room.

They’re not listening. They’re just waiting for me to finish talking

.

Mia went up to her room in the attic and started practicing. When it came to her music, she never slacked off. She’d been

playing the guitar for two years, and for a year and a half she’d been a vocalist in the band Rogue Squadron, a name with

a nod to the seventies appropriate for a punk band that sort of sounded like something from another era, maybe 1982. Or 1984.

Even though she didn’t always care about getting every last little bit of her homework done, she made sure she knew her music

history better than anyone.

Her latest discovery was the Talking Heads, a band she had slowly but surely fallen in love with. Or, rather, that she was

doing her best to fall in love with, because she could tell it was good. She still struggled a little when she listened for

a long time. And she wasn’t quite sure if the music was post-punk or rock or just pop, and that made the whole thing even

more complicated. But it had such a cold, electronic eighties sound, she knew it would be a perfect fit for her if she could

just get into the music.

She kept practicing her guitar for an hour and wrote a draft for a new song that worked off a riff she’d stolen from songs

she was totally sure no one had heard. It would be okay to show up with that at her band’s rehearsal tomorrow. After she’d

played through it five times and was pretty sure she remembered the chords, she set her guitar down, plugged her headphones

into the stereo, and pressed

play

. Music from the band she had decided to start liking filled her ears. She lay back on the bed and closed her eyes.

“What are you listening to, Mia?” her dad asked, raising one side of her headphones. He was trying to smooth over the negative

vibe from earlier in the day.

“Talking Heads,” she answered.

“You know they were really popular when I was young.”

Mia gave him a look but didn’t respond.

“You know, it’s an amazing opportunity, Mia, the moon. I —

we —

just want what’s best for you. You know that.”

She groaned but tried to smile at him anyway. “Dad, please. Just drop it, okay?”

But he wouldn’t drop it.

“And for your band, have you given that any thought? Don’t you guys want to be famous? I don’t think it would hurt Rough Squadron

in terms of publicity if the vocalist were a world-famous astronaut.”

“

Rogue

Squadron,” she corrected.

“Anyway,” he replied, “you know what I mean.” And then he left, shutting her door carefully behind him.

Mia lay down on her bed again. Was there something to what he said? No, there wasn’t. She was a musician, after all. Not some

astronaut wannabe. She turned her music on again, and vocalist David Byrne sang: “

I don’t know what you expect staring into the TV set. Fighting fire with fire.”

It was almost May, but the air was still chilly in Norway. The trees lining the avenue were naked and lifeless with the exception

of a couple of leaves here and there, which had opened too early. Two weeks had passed since Mia’s parents had suggested their

silly idea to her.

Now she was standing outside school, scraping her boots back and forth over the ground as she waited for Silje to come back

from the bathroom. Lunch break would be over soon, and around her other students were scurrying back into the building for

fear they’d be late. But Mia was not in any hurry. The teachers always came to class a few minutes late anyway. They sat up

there in the teachers’ lounge eating dry Ritz crackers and drinking bitter coffee while they trash-talked individual students.

Mia felt her school was the kind of place where the teachers, with a few decent exceptions, should have gone into pretty much

any profession other than teaching. Janitorial work, for example. Or tending graveyards. Something where they didn’t need

to interact with living people. Most of them had just barely squeaked through their teaching programs about a hundred years

earlier. They had almost infinite power here, and they did their best to remind the students of that every chance they got

— because they all knew that this authority disappeared like dew in the sunlight the second they left school grounds and headed

out into the real world, where they were forced to interact with people their own age.

Silje came out of the bathroom. She and Mia were the only ones who hadn’t gone back inside yet.

“Cool boots,” Silje said.

“I’ve been wearing them all day,” Mia replied drily. “Didn’t you notice?”

“Not until now. Where’d you get them?”

Mia looked down at her worn, black leather boots that laced up just above the ankle. “Online. Italian paratrooper boots.”

“Awesome,” Silje said. “Well, should we go in?”

“What do you have now?”

“Math,” Silje said.

“I have

Deutsch

. With ‘the Hair,’” Mia said with a sigh.

They went back in and took the stairs up to the second floor.

“Are we rehearsing tonight?” Silje asked right before they went their separate ways.

“I think so. Leonora’s going to call me as soon as she knows if she can.”

“Let me know, okay? I can be there at seven. Not before.”

“Seven’s fine. Hey, I wrote a new song yesterday.”

“You did? What’s it called?”

“ ‘Bomb Hiroshima Again,’ I think. I haven’t decided yet.”

“Cool,” Silje said with a laugh. “See you later.”

Mia continued on to the third floor and walked into the classroom. The teacher wasn’t there yet, so she skimmed through her

German book to figure out what in the world she was supposed to have read the night before.

The Hair came sailing into the classroom with an inflatable beach ball shaped like a model of the moon in her hands. Mia rolled

her eyes.

Oh my God, not her, too

.

But, yes, the Hair — this tiny lady with the freakishly big hair — had caught moon fever. She disappeared behind her desk

and started blabbering on in German about how exciting the whole thing was and how great it would be if one of her students

ended up being selected.

Mia rolled her eyes again. It was a known fact that the Hair had been at this school too long. She only taught German and

home ec. And then there was her big secret, which everyone knew but which she thought was well kept: The Hair had never been

to Germany. She had only ever left Norway once, to go to Sweden. And that was back in the summer of 1986 or thereabouts, and

she had come home again after four days.

But maybe the fact that she was now standing in front of them with that inflatable moon under her arm wasn’t as strange as

one might think. The whole world had come completely unhinged this winter. The newspapers, the radio, the TV, and the Internet

were flooded with moon mania every day, from

trivia and data spouted by experts and professors and astronomers to competitions where you could win all sorts of stuff just

by answering a few simple questions about space travel. Meanwhile, millions of teenagers were busy logging on or standing

in long lines at registration desks in malls or grocery stores in just about every single town in the whole world to make

sure that their names had been entered.

For safety reasons, NASA had decided that the three young people who would be chosen to go must be at least fourteen and that

they couldn’t be older than eighteen. They would also need to be between five feet four inches and six feet four inches tall,

undergo a psychological examination performed by a certified practitioner in their hometown, and pass a general physical examination

in order to obtain a medical “green card.” All applicants should have a near and distant visual acuity correctable to 20/20

and a blood pressure, while sitting, of no more than 140 over 90. And then there were all the tests and training they would

be put through in the unlikely event that they were among the selected few.

While these requirements restricted the number of candidates somewhat, millions of names had been submitted for the big drawing,

and as the days and weeks went by, people were close to bursting with excitement. Gamblers put money on which countries the

lucky three would come from and on whether the winners would include more boys or girls. Talk show hosts invited experts to

speculate about nonsense like the effect of seeing Earth from space on people so young. And then there were the debates that

were as numerous as they were endless about this moon base that no one had ever heard mention of before now.

What was it? Why was it there? What did it do? Could people really trust that it had been built with peaceful intentions?

The Hair reached the end of her speech and switched into broken Norwegian, which often happened whenever she spoke German

for too long. “But listen to this. Someone representing NASA — yes,

the

NASA — called our school to check in with our students about signing up for the lottery. As I’m sure you’ve heard, any school

with one hundred percent participation by their eligible students will be entered in a sweepstakes for a grant for technology

upgrades. The representative from NASA said that a whopping ninety-one from your grade have already signed up and asked us

to encourage the rest of you to do so as well. But only five of you from my German class have taken advantage of this incredible

opportunity.”

No one said anything.

“Well done, Petter, Stine, Malene, and Henning.”

The four students who’d signed up smiled at her smugly.

“And Mia, what a nice surprise. Congratulations.”

Mia stiffened completely and said, “I didn’t sign up for anything.”

“Well, according to NASA, you did.”

Mia leaned over her desk and said loudly, “Well then, they must have made a mistake! I totally

didn’t

sign up for that stupid-ass lottery.”

“Calm down, Mia. It’s nothing to be self-conscious about.”

“I’m not embarrassed about it. It’s just not true. And even if it were, NASA shouldn’t be releasing that kind of information

to anyone.”

The Hair waved her hand dismissively and winked at her, as if

they were both in on some secret. “Evidently it was a condition of the sign-up procedure that you give NASA permission to

reveal your name as a participant in the lottery. But we don’t need to dwell on this. It’s up to each individual to decide

if he or she wants to consider doing it or not.”

“What’s your point?” Mia railed, rage welling up inside. “I told you I didn’t sign up for that thing. What the hell would

I do in space, anyway? Don’t you think I have better things to do? Screw the moon!”

“We don’t use language like that in my classroom, Mia!”

“No,

we

don’t talk at all in your classroom.

You

just go off on hour-long monologues about whatever bullshit you feel like!”

The teacher stood and pointed to the door. “You’re excused from the rest of the class, Mia. I don’t want you here. You can

wait out in the hall.”

Mia didn’t protest. She brushed her German book off the edge of her desk so it landed in her backpack, got up, and left. The

hallway was empty, and from the surrounding classrooms she could hear snippets of Norwegian, math, and English classes going

on. Without thinking, she opened the door to her classroom again and stared straight at the Hair.

“Besides, everyone knows you’ve never been to Germany. Maybe that’s something

you

should be embarrassed about?” For half a second her teacher’s face became long and sad, as if she’d been sentenced to life

in prison for a nasty crime she forgot she’d committed.