1938 (32 page)

Authors: Giles MacDonogh

Weizsäcker clearly thought the personal audience a terrible idea, while Chamberlain for his part seemed reluctant to see the gravity of the situation. The British had never had any serious intention of fighting for Czechoslovakia. This message either failed to get through or was not seriously entertained by the Germans in the opposition so bent on ridding their country of Hitler. Beck was out of the picture, but continuity was to some extent assured by the new chief of staff, Halder, who agreed to depose Hitler on September 2.

At an emergency meeting of the British cabinet on August 30, it had been decided to make Beneš accept Henlein’s Karlsbad Program and accord virtual autonomy to the Germans. Responding to British pressure, Beneš tried making concessions: He was prepared to take in four Sudeten German ministers, declare three German autonomous districts, and make sure that a third of all civil servants were ethnic Germans from now on. His more reasoned tone received British backing, but Hitler instructed Henlein to stay firm and make no concessions.

On the 3rd Keitel and Brauchitsch arrived at the Berghof to run over the plans for the invasion of Czechoslovakia. The army was to be ready at the border on September 28. Two days later, Beneš tried to spike Hitler’s strategy by asking Henlein up to the Hradschin on the 5th and requesting that he write down his demands in full so that he might grant them. He promptly did this on the 7th, thereby removing the casus belli. All Henlein could do was point to the ill treatment of some ethnic Germans in Moravia and seek fresh instructions from Germany. Meanwhile his second-in-command, Karl Frank, was instructed to increase the number of such incidents.

It was said that the Czechs were prepared to give Henlein a ministry to shut him up. The ministry he wanted was the Interior. The story gave rise to inevitable witticisms. It is said that the premier, Hodza, had suggested that Henlein instead receive the portfolio for the colonies. At this Henlein countered, “That’s impossible—Czechoslovakia has no colonies.” “What of it?” replied Hodza. “Has not Italy a Minister of Finance and Germany a Minister of Justice?”

On the evening of September 4th, the chief warmongers—Hitler, Goebbels, and Ribbentrop—flew to Nuremberg for the annual party rally. Goebbels was looking forward to a week of putting pressure on the Czechs. That same day France called up its military reserves, and the Hungarians quietly introduced conscription. War was becoming inevitable.

The rally opened on the 6th with Hess delivering what Goebbels called “a good sermon.” The Tribune of Honor at the opening ceremony exhibited evidence that Hitler continued to exert a powerful erotic pull on the women of the world. At one end was Stephanie zu Hohenlohe and at the other Lord and Lady Redesdale, the parents of Unity Mitford. Princess Stephanie was wearing her gold Party badge. The rally kicked off with the “Cultural Conference,” and Hitler made a portentous speech about art, as was his wont. It contained an unusually tolerant line about freemasons: Hitler said that “only a man lacking in national respect” would allow them to get in the way of his enjoying Mozart’s

Magic Flute

.

Once the cultural overture was out of the way, the Nazi leaders descended into their habitual rabble-rousing tirades and malicious squabbles. Rosenberg launched an attack on the pope’s pretensions to power. He would have had support from Goebbels; a new Kulturkampf against the Church was never far from the gauleiter’s mind. Goebbels was thrilled that he had succeeded in eliminating the exemption from military service previously enjoyed by theological students. Now they had to serve in the front line as stretcher-bearers.

Backbiting was not confined to the leaders: Their aim was to eliminate the ideological enemies of the Reich: Jews, freemasons, Marxists, and the Church. Unity took the trouble to warn Hitler that his friend Stephanie was 100 percent Jewish. She was also advising Hitler that Britain would not fight, thereby supporting Ribbentrop. The brief reconciliation between Hitler’s two biggest hawks, Goebbels and Ribbentrop, had ended. Goebbels now thought the foreign minister a “vain, stupid prima donna.” As usual, Hitler appeared to take no notice of the discord among his underlings. He was planning a positive cacophony of saber rattling for the last day of the rally, September 12. The British ambassador, Henderson, was present, eating the local

Bratwürste

and disparaging the Czechs to his SS minder. Officially, he was meant to push the idea of holding a plebiscite in the disputed areas, which would hand the initiative to the Czechs. An article in the

Times

had advocated the cession of the Sudetenland to Germany. The leading Nazis believed this had been placed by the cabinet. Henderson thought Hitler had been led astray by evil people in his entourage, and if the British were to say what a good boy he was, he would behave better. His view was not shared by Halifax, who was now of the opinion that Hitler was mad.

But Hitler was impervious to any form of pressure to desist—be it from his diplomats; his own intelligence service, which brought him news of the Duce’s unhappiness; or the army. Goebbels’s admiration for his master knew no bounds: “He faces danger with the surefootedness of a sleepwalker.” “The Führer says and does what he knows to be right, and never lets himself be intimidated.” “Now the most important things are nerves.” Goebbels was utterly convinced that the Western powers would stay out of any conflict. Despite his outward resolve, Hitler was less certain.

The 7th was cold and wet. Goebbels noted, “Things are ripening more and more into a crisis.” The British, Dutch, and Belgian armies called up their reserves. The British offer of autonomy for the Sudetenland was now insufficient: “We have to have Prague,” he gloated, for news of a couple of German deaths in Mährisch Östrau would permit a new, deafening chorus of Nazi outrage.

At a reception that evening for the diplomatic corps in Nuremberg, the doyen, the outgoing French ambassador, André François-Poncet (whom Spitzy called an “all-licensed fool”), made a speech in which he said, “The best of laurels are those gathered without reducing any mother to tears.” All eyes turned to Hitler. In Berlin there was frenzied activity in resistance circles, where the plan was to seize Hitler and put him on trial before the People’s Court or lock him up in a lunatic asylum. On September 9, following the usual son et lumière, Hitler held an all-night conference in Nuremberg attended by Halder, Brauchitsch, and Keitel. He was contemptuous of the army’s plans and demanded there be an immediate uprising in the Sudetenland.

ON THE 9TH, refreshed from his shooting, Chamberlain met his Inner Cabinet. He rejected Halifax’s proposal of sending a final warning to Germany and revealed his desire to go to Hitler directly, though he nonetheless set about mobilizing the fleet. He also issued a warning to Hitler on the 10th, that France would be duty bound to honor its obligations to the Czechs and Great Britain could not stand aside from any general conflict. Henderson had qualms about delivering this ultimatum, and it remained in his baggage. He had difficulty meeting Hitler anyway and had been frightened that any tough talk—or even a toughly worded note—might upset the German leader. He didn’t even attempt to speak to Ribbentrop, thereby causing exasperation in some quarters. The message the Germans received was that Britain would agree to the cession of the German areas but would not permit a strike against Prague. “That would be disappointing, as it is only the half-measure,” wrote Goebbels, who showed that he was well-aware of Chamberlain’s message despite Henderson’s refusal to deliver it.

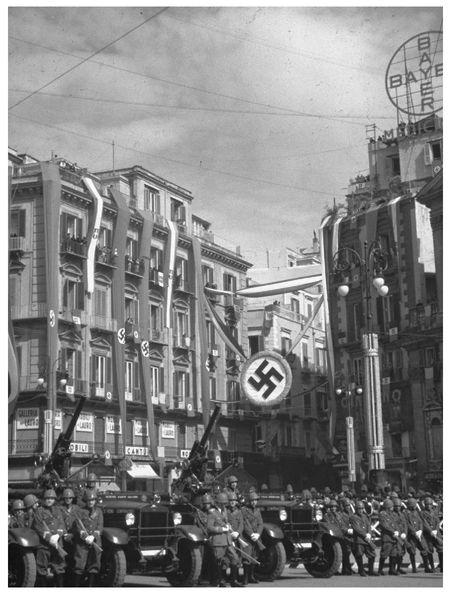

ITALY

Hitler’s “Roman Holiday” in May: The Nazi leaders assemble with Mussolini on the steps of the monument to Victor Emmanuel II.

Hitler felt certain Italians were looking down on him. After an incident at the opera in Naples, he sacked his chief of protocol.

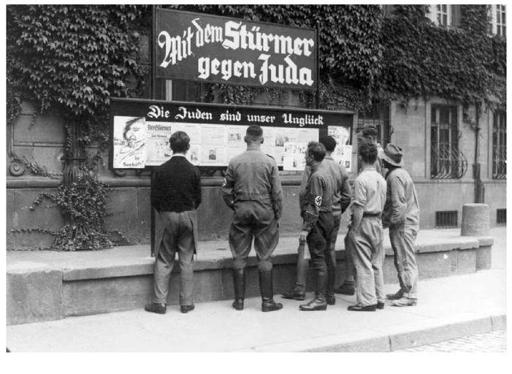

DER STÜRMER

Der Stürmer

. Germans read cases containing copies of the magazine that was the unofficial organ of Nazi antisemitism.

“Jewish Advertising Revenue: The so-called pressure of public opinion is the weight of Jewish sacks of gold.”

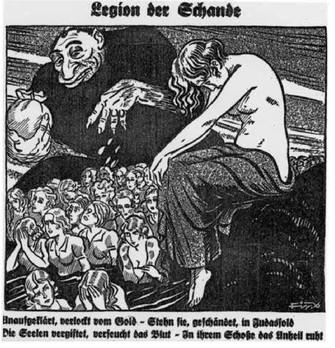

ANTISEMITIC PROPAGANDA

Antisemitic propaganda cartoons from

Der Stürmer

. Aryan woman defiled by Jewish gold.