1968 (61 page)

In the year 2000, Myrthokleia González Gallardo happened across a friend from student times who was amazed to see her. All these years the friend had assumed Myrthokleia had been killed in the plaza.

In 1993, for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the massacre, the government gave permission for a monument to be placed in the plaza. Survivors, historians, and journalists searched for the names of victims but could come up with only twenty names. There was another effort in 1998 that yielded only a few more names. Most Mexicans who have tried to unravel the mystery estimate that between one hundred and two hundred people were killed. Some estimates are higher still. Someone was seen filming from a distance on one of the high floors of the Foreign Ministry, but the film has never been found.

After October 2, the student movement dissolved. The Olympics progressed without any local disturbances. Gustavo Díaz Ordaz’s chosen successor was Luis Echeverria, the minister of the interior who worked with him on repressing the student movement. Until he died in 1979, Díaz Ordaz insisted that one of his great accomplishments as president was the way he handled the student movement and averted any embarrassment during the games.

But very much in the same way that the invasion of Czechoslovakia was the end of the Soviet Union, Tlatelolco was the unseen beginning of the end of the PRI. Álvarez Garín said in a remarkably bold 1971 book on the massacre by Mexican journalist Elena Poniatowska, “All of us were reborn on October 2. And on that day we also decided how we are all going to die; fighting for genuine justice and democracy.”

In July 2000, for the first time in seventy-one years of existence, the PRI was voted out of power, and it was done democratically, in a slow process over decades, without the use of violence. Today the press is far more free and Mexico much closer to being a true democracy. But it is significant that even with the PRI out of power, many Mexicans said they were afraid to be interviewed for this book, and some who had agreed, upon reflection, backed out.

The tall rectangular slab erected for the twenty-fifth anniversary lists the ages of the twenty victims. Many were eighteen, nineteen, twenty years old. At the bottom it adds, “

y muchos otros campañeros cuyos nombres y edades aún no conocemos

”—and many more comrades whose names and ages are unknown.

Every year in October, Mexicans of the ’68 generation start crying. Mexicans have a very long memory. They still remember how the Aztecs abused other tribes and argue over whether the princess Malinche’s collaboration with Cortés, betraying the Aztec alliance, was justifiable. There is still lingering bitterness about Cortés. Nor is it forgotten how the French connived to take over Mexico in 1862. The peasants still remember the unfulfilled promises of Emiliano Zapata. And it is absolutely certain that Mexicans will long remember what happened on October 2, 1968, amid the Aztec ruins of Tlatelolco.

PART IV

THE FALL

OF NIXONIt is not an overstatement to say that the destiny of the entire human race depends on what is going on in America today. This is a staggering reality to the rest of the world; they must feel like passengers in a supersonic jet liner who are forced to watch helplessly while a passel of drunks, hypes, freaks, and madmen fight for the controls and the pilot’s seat.

—E

LDRIDGE

C

LEAVER,

Soul on Ice,

1968

CHAPTER 20

THEORY AND PRACTICE

FOR THE FALL SEMESTER

Do you realize the responsibility I carry? I am the only person standing between Nixon and the White House.

—J

OHN

F

ITZGERALD

K

ENNEDY,

1960

I believe that if my judgment and my intuition, my gut

feeling, so to speak about America and American political

tradition is right, this is the year that I will win.

—R

ICHARD

M.

N

IXON,

1968

P

RESIDENT GUSTAVO DíAZ ORDAZ

of Mexico formally proclaimed the opening of the games of the

XIX Olympiad yesterday in a setting of pageantry, brotherhood

and peace before a crowd of 100,000 at the Olympic Stadium in

Mexico City.” So read the lead on page one of

The New York Times

and in major newspapers around the world. Díaz Ordaz got

the coverage he had killed for. The dove of peace was the

symbol of the games, decorating the boulevards where students

were lately beaten, and billboards proclaimed,

“Everything Is Possible with Peace.” It was

generally agreed that the Mexicans were running a good show,

and the opening ceremonies were hailed for pomp as each team

presented its flag to the regally perched Díaz Ordaz,

El Presidente,

the former El Chango. And no one could help but be moved as the

Czechoslovakian team marched into the stadium to an

international standing ovation. For the first time in history,

the Olympic torch was lit by a woman, which was deemed

considerable progress since the ancient Greek Olympics, where a

woman caught at an Olympiad was executed. There was no longer

any sign of the student movement in Mexico, and if it was

mentioned, the government simply explained in the face of all

logic that the movement had been an international communist

plot hatched by the CIA. Yet the size of the crowd was

disappointing to the Mexican planners. There were even empty

hotel rooms in Mexico City.

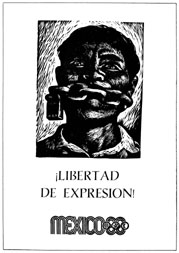

“Freedom of expression.” 1968 student

silk-screen poster with the logo of the Mexico City Olympics

at the bottom

(Amigos de la Unidad de Postgrado de la Escuela de

Diseño A.C.)

The United States, as predicted, assembled one of the best

track and field teams in history. But then politics began to

chip away at it. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, receiving gold

and bronze medals for the 200-meter dash, came to the medal

presentation shoeless, wearing long black socks. As the U.S.

national anthem played, each raised one black gloved hand in

the fist that symbolized Black Power. It looked like a

spontaneous gesture, but in the political tradition of 1968,

the act was actually the result of a series of meetings between

the athletes. The black gloves had been bought because they had

anticipated receiving the medals from eighty-one-year-old Avery

Brundage, the president of the International Olympic Committee,

who had spent most of the year trying to get South

Africa’s segregated team into the games. Certain that

they would win medals, they planned to use the gloves to refuse

Brundage’s hand. But in a change of plans, Brundage was

at a different event. Observant fans might have noticed that

they had split one pair of gloves, Smith using the right hand

and Carlos the left. The other pair of gloves was worn by

400-meter runner Lee Evans, a teammate and fellow student of

Harry Edwards’s at San Jose State. Evans was in the

stands returning the Black Power salute, but no one

noticed.

The next day Carlos was interviewed on one of the principal

boulevards of Mexico City. He said, “We wanted all the

black people in the world—the little grocer, the man with

the shoe repair store—to know that when that medal hangs

on my chest or Tommie’s, it hangs on his

also.”

The International Olympic Committee, especially Brundage,

was furious. The American contingent was divided between those

who were outraged and those who wanted to keep their

extraordinary team together. But the committee threatened to

ban the entire U.S. team. Instead they settled for the team

banning Smith and Carlos, who were given forty-eight hours to

leave the Olympic Village. Other black athletes also made

political gestures, but the Olympic committee seemed to go out

of its way to find reasons why these offenses were not as

severe. When the American team swept the 400-meter, winners Lee

Evans, Larry James, and Ron Freeman appeared at the medal

ceremony wearing black berets and also raising their fists. But

the International Olympic Committee was quick to point out that

they didn’t do this while the national anthem was being

played and therefore had not insulted the flag. They in fact

removed their berets during the anthem. Also, much was made of

the fact that they were smiling when they raised their fists.

Smith and Carlos had been somber. And so, as in the days of

slavery, the smiling Negro with a nonthreatening posture was

not to be punished. Nor did bronze medal–winning long

jumper Ralph Boston, going barefoot in the ceremonies, achieve

condemnation for his protest. Long jumper Bob Beamon, who on

his first attempt jumped 29 feet 2.5 inches, breaking the world

record by almost 2 feet, received his long jump gold medal with

his sweat pants rolled up to show black socks, which was also

accepted.

The original incident at the medal presentations of Smith

and Carlos attracted almost no attention in the packed Olympic

stadium. It was only the television coverage, the camera

zooming in on the two as though everyone in the stadium were

doing the same, that made this one of the most remembered

moments of the 1968 games. Smith, who had broken all records

running 200 meters in 19.83 seconds, had his career in sports

overshadowed by the incident, but whenever asked he has always

said, “I have no regrets.” He told the Associated

Press in 1998, “We were there to stand up for human

rights and to stand up for black Americans.”

On the other hand, an unknown nineteen-year-old black boxer

from Houston had his career shadowed by the Olympics for doing

the reverse of Smith. After George Foreman won the heavyweight

gold medal in 1968 by defeating the Soviet champion Ionas

Chepulis, he pulled out from somewhere a tiny American flag.

Had he been carrying it during the fight? He began waving it

around his head. Nixon liked the performance and contrasted him

favorably with those other antiwar young Americans who were

always criticizing America. Hubert Humphrey pointed out that

the young man with the flag when interviewed in the ring had

saluted the Job Corps that Nixon was threatening to disband.

But to many boxing fans, especially black ones, it had seemed

like a moment of Uncle Tomism, and when Foreman went

professional some started referring to him as the Great White

Hope, especially when he faced the beloved Muhammad Ali, who

beat him in an upset in Zaire, where all of black Africa and

much of the world cheered Ali’s victory. It was a

humiliation from which Foreman did not recover for years.

Yet through this year of upheavals and bloodshed, the

baseball season glided eerily, as false and happy as a Norman

Rockwell painting. Names like Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris,

Maris now traded to the St. Louis Cardinals, were still popping

up, names that belonged to another age, before there were the

sixties, before the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, when most

Americans had never heard of a place called Vietnam. On April

27, less than a mile from besieged Columbia University, Mickey

Mantle hit his 521st home run against the Detroit Tigers, tying

Ted Williams for fourth place in career home runs. The night

Bobby Kennedy was shot in Los Angeles, the Dodgers were playing

in town and thirty-one-year-old right-handed pitcher Don

Drysdale threw his sixth consecutive shutout, this time against

the Pittsburgh Pirates. This broke Doc White’s

sixty-four-year-old record for consecutive shutouts. On

September 19, the day before the Mexican army seized UNAM,

Mickey Mantle hit his 535th home run, breaking Jimmie

Foxx’s record, to become the third-biggest career home

run producer in history, behind only Willie Mays and Babe Ruth.

The massacre at Tlatelolco shared front pages with the

Cardinals’ Bob Gibson, who, while the massacre was

unfolding, struck out seventeen Detroit Tigers in the opening

game of the World Series, beating Sandy Koufax’s

memorable fifteen strikeouts against the Yankees in 1963.

Baseball was having a great season, but it was getting

difficult to care. Attendance was low in almost every stadium

except Detroit, where the Tigers had their first good team in

memory. Some of the stadiums were in neighborhoods associated

with black rioting. Some fans thought that the pitching had

gotten too good at the expense of hitting. Some thought that

football, with its fast-growing audience, was more violent and

therefore better suited to the times. The 1968 World Series was

expected to be one of history’s finest pitching duels,

between Detroit’s Denny McLain and St. Louis’s Bob

Gibson. It was a seven-game series in which the Tigers, after

losing three out of four games, came back to win the next

three, thanks to the unexpectedly brilliant pitching of Mickey

Lolich. For baseball fans it was a seven-game break from the

year 1968. For the rest, Gene McCarthy—who was said to

have been a respectable semiprofessional first

baseman—said that the best ball players were men who

“were smart enough to understand the game and not smart

enough to lose interest in it.”

The only thing as out of step with the times as baseball

was Canada, which was in the strange embrace of something

called Trudeaumania. This country that became the home to an

estimated fifty to one hundred U.S. military deserters and

hundreds more draft dodgers was becoming a weirdly happy place.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau became the new Liberal prime minister of

Canada. Trudeau was one of the few prime ministers in the

history of Canada to have been described as flashy. At

forty-six and unmarried, he was the kind of politician whom

people wanted to meet, touch, kiss. He was known for his

unusual dress, sandals, a green leather coat, and for other

unpredictable whimsy. He even once slid down the bannister of

the House of Commons while holding piles of legislation. He

practiced yoga, loved skin diving, and had a brown belt in

karate. He had a stack of prestigious graduate degrees from

Harvard, London, and Paris and until 1968 was known more as an

intellectual than a politician. In fact, one of the few things

he was not known to have experienced very much of was

politics.

As Americans faced the bleak choice of Humphrey or Nixon,

Time

magazine captured the thinking of many Americans when it

wrote:

The U.S. has seldom had occasion to look north to Canada

for political excitement. Yet last week, Americans could envy

Canadians the exuberant dash of their new Prime Minister Pierre

Elliot Trudeau who, along with intellect and political skill,

exhibits a swinger’s panache, a lively style, an

imaginative approach to its nation’s problems. A great

many U.S. voters yearn for a fresh political experience. . .

.

In a time of extremism, he was a moderate with a lefty

style, but his exact positions were almost impossible to

establish. He was from Quebec and of French origin, but he

spoke both languages beautifully and it was so uncertain whose

side he was on that many hoped he might be able to resolve the

French-English squabble that consumed much of Canada’s

political debate. While most Canadians were against the war in

Vietnam, he said he thought the bombing should halt but that he

was not going to tell the United States what to do. A classic

Trudeauism: “We Canadians have to remember that the

United States is kind of a sovereign state too.” He was

once apprehended in Moscow for throwing snowballs at a statue

of Stalin. But he was sometimes accused of communism. Once,

when asked flat out if he was a communist, he answered:

“Actually I am a canoeist. I’ve canoed down the

Mackenzie, the Coppermine, the Saguenay rivers. I wanted to

prove that a canoe was the most seaworthy vessel around. In

1960 I set out from Florida to Cuba—very treacherous

waters down there. Some people thought I was trying to smuggle

arms to Cuba. But I ask you, how much arms can you smuggle in a

canoe?”

It is a rare politician who can get away with answers like

that, but in 1968, with the rest of the world turned so

earnest, Canadians were laughing. Trudeau, with his lack of

political experience, would say that the voters had put him up

to running as a kind of joke. And now they “are stuck

with me.” Fellow Canadian Marshall McLuhan described

Trudeau’s face as a “corporate tribal mask.”

“Nobody can penetrate it,” McLuhan said. “He

has no personal point of view on anything.”

On social issues, however, his position was clear. Despite

a reputation for womanizing, he took strong stands on

women’s issues, including liberalizing abortion laws, and

he was also an outspoken advocate of rights for homosexuals.

Prior to the April election, Trudeau had always been seen in a

Mercedes sports car. A reporter asked him, now that he was

prime minister, whether he was going to give up the Mercedes.

Trudeau answered, “Mercedes the car or Mercedes the

girl?”