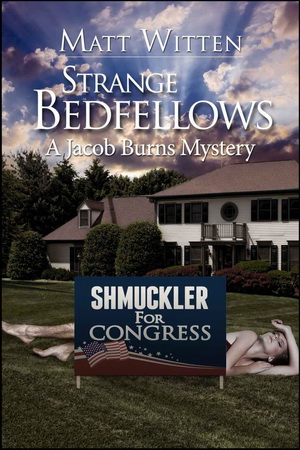

3 Strange Bedfellows

Read 3 Strange Bedfellows Online

Authors: Matt Witten

Praise for STRANGE BEDFELLOWS

and the Jacob Burns Mysteries

“Witten delights with his charming characters, especially Burns himself.” –

Publishers Weekly

“

Told with warmth and wit, STRANGE BEDFELLOWS is a wry story that packs a wallop of an ending.” –

Romantic Times

“STRANGE BEDFELLOWS is a mystery that takes some strange twists and turns and ends up in a place few readers will expect. The plot is fast moving… Jacob is a very real, very likable character. He has a wry sense of humor and the dialogue is crisp and funny. Andrea, Jacob’s wife, is a strong supporting character… and the Burns’ boys add a unique child’s perspective. The third book in the series, STRANGE BEDFELLOWS doesn’t lose the edge of the earlier two mysteries. Jacob and his family remain fresh characters, the storylines unique, providing good, fun entertainment for all.” –

The Mystery Reader

“The pace is swift; the elements fit together neatly; the writing is assured, on-target, and often amusing, and the characters well-drawn and likable… As well-crafted as they come.” –

The Drood Review of Mystery

“A success. Fast…lighthearted… Witten presents his characters and plot twists in a straightforward and believable manner.”

– Albany Times-Union

“

Interesting characters, a substantial plot, and a subtle sense of humor.” –

The Mystery News

“STRANGE BEDFELLOWS is a treat for amateur-sleuth gourmets.” -

BookBrowser

“An enjoyable cozy with well-drawn characters.” –

The Charlotte Austin Review

“Charming, witty and moving…an irresistible read. Jacob Burns is a welcome addition to crime fiction.” – Don Winslow, author of

Savages

“A winner. Mystery fans are going to love this guy.” – Laura Lippman, author of

The Most Dangerous Thing

"Jacob Burns is a wise-cracking, write-at-home dad with a nose for trouble. While solving mysterious deaths in Saratoga Springs, he manages to see into the heart of his community with a great deal of humor and tenderness." — Sujata Massey, Agatha Award-winning author of the Rei Shimura mysteries

For my father

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank my literary agent, Jimmy Vines; my editor, Joe Pittman; and the folks who helped me along the way: Carmen Bassin-Beumer, Betsy Blaustein, Nancy Butcher, Navorn Johnson, Leslie Schwartz, Larry Shuman, Benson Silverman, Robert Tompkins, Jeffrey Wait, Justin Wilcox, Celia Witten, and everybody at Malice Domestic, the Creative Bloc, and the late, lamented Madeline's Espresso Bar.

I wish to express special gratitude to Jean Bordewich for running for Congress from the 22nd District and giving the voters a good choice.

Finally, many thanks to Nancy Seid, who is not only my wife and girlfriend, but also a darn fierce editor.

WARNING:

This book is fiction! The people aren't real! Nothing in it ever happened!

1

When longtime congressman Mortimer "Mo" Wilson died suddenly last spring after eating some bad sushi, my old pal Will called me that same night. "Jake," he boomed excitedly, "I'm considering running for Congress. What do you think?"

"I think, take two aspirin and a pint of Jose Cuervo and call me in the morning."

"Come on, this district is ready for a change. It's a whole new millennium

—"

"Make that a quart."

I mean, who was he trying to kid? Our district in the wilds of upstate New York hadn't elected a Democrat since the Great Depression. It hadn't

ever

elected someone of the Hebraic persuasion. And Will was both.

Not only that, he was saddled with the unfortunate last name of Shmuckler. Tell me, would you vote for some guy named Will

Shmuckler?

But Will ignored my advice. After the governor called a special election to fill the vacant seat, Will won the Democratic primary, running unopposed

—no one else bothered. Now he was going head to head against the Republican, an empty suit named Jack "the Hack" Tamarack. The Hack had kissed high-powered GOP butt for two decades, most recently as legal counsel to the Republican State Senate Majority, and he was finally getting his reward: the safest seat in the entire U.S. House of Representatives.

Technically speaking, the Republicans had a primary, too. But the party

muckymucks funneled enough TV ad money to the Hack so he could bury any dreamers foolish enough to oppose him. And once he had the GOP nomination . . . well, in the 22nd District, if you ran Robert Redford as a Democrat and a ringtail monkey as a Republican, the monkey would win—as long as he was against gun control.

So with the special election fast approaching and Will calling me frantically ten times a day to pass out leaflets, host candidate's coffees, and so on, I had no trouble whatever restraining my nonexistent enthusiasm. Years ago, as a wee young sprat, I had been "clean for Gene" McCarthy, canvassed for George McGovern, and spent the winter of 1975-76 tramping the snows of New Hampshire for Morris Udall, the best one-eyed candidate ever to run for president. Now, though, I was forty-one, with two kids in elementary school. I was way too old and way too busy for romantic lost causes.

And yet, somehow I did end up passing out those leaflets and hosting those coffees. I had no choice. See, the Shmuck (my affectionate nickname for him) was my freshman-year college roommate. We chased Holyoke girls and Smithies together, discussed The Meaning of Life in our dorm bathroom together, and one memorable Saturday night even puked our guts out from the same bottle of Mr. Boston Blackberry Brandy.

These days Will lived way down at the southern end of the 22nd District, over an hour away, so we hardly ever saw each other. Our lives had diverged in other ways, too: he'd stayed in the political sphere as an environmental lawyer, while I got into the writing biz. But the old ties between us still remained strong, like an old Bob Dylan song that stirs your innards even twenty-five years later.

So I did what Will asked. Eventually I found myself practically running the Saratoga County part of his campaign. My modest three-bedroom home in the town of Saratoga Springs turned into his local headquarters. By the beginning of September I could hardly wait until the big vote, two weeks away, so I could get my life back. And get all those darn leaflets off my dining room table.

The final straw came when he awakened me from a deep sleep on the night before my kids' first day of school. He barely had a chance to get out "Hi, it's me," before I interrupted him.

"Shmuck, it's past midnight. I don't want to talk about your campaign—"

"That's not why I'm calling."

I heard a hubbub of background noises and an intercom. It sounded like a train station—or a hospital. "Where are you?" I asked in alarm. "You okay?"

"Not exactly. I'm in jail."

He sounded strangely calm.

"Jail?

What for?" I shouted.

Now his fake

sangfroid

gave way to a desperate cry. "I swear to God, I didn't kill him!"

"Kill

who?!"

"The Hack," he said. "Somebody shot the Hack."

2

Early the next morning, my wife and I took our sons Derek Jeter and Bernie Williams to the bus stop for their first day of school. Their real names are Daniel and Nathan, but when they became rabid New York Yankee fans, they changed their monikers. (For those of you who never crack the sports pages, the original Derek J. and Bernie W. are Yankees who've won the World Series more often than I can count.)

Our boys used to call themselves Babe Ruth and Wayne Gretzky, and then Leonardo and Raphael

—after the Ninja Turtles of course, not the painters. As Andrea and I waved good-bye to them through the bus window that morning, we both had tears in our eyes. Kids are such weeds. How long would our sweet little boys stay Derek and Bernie? By this time next year, would they be Hulk Hogan and Macho Man, or Shaquille and Kobe, or Pikachu and Charizard?

Derek was in second grade already, an old pro at this whole school bus thing, but Bernie was just a kindergartner. He clutched his older brother's hand and tried to look brave, but it was obvious he was churning inside.

Maybe it was fortunate that I didn't have time to dwell on my own muddled emotions that morning. I was on my way down south to Troy, to try to help Will beat his murder rap.

Why me? you may ask. Well, oddly enough, I had developed something of a reputation as a guy who could solve murders. I'd gotten mixed up in a couple of them

— through no fault of my own, I hasten to add. So it made sense that when Will was accused of shooting someone, he'd come to me for help. And it made sense that I'd say yes.

No question about it, Will Shmuckler had his flaws. He was too much of a starry-eyed idealist for my increasingly curmudgeonly and middle-aged tastes. He was also way too much of a Boston Red Sox fan, a condition that I'm convinced leads to insanity. But despite that, I was pretty sure he wouldn't kill anyone

—even someone who probably deserved it, like Jack the Hack.

I had to admit, though, the circumstantial evidence I'd read that morning in the

Daily

Saratogian

sounded awfully damning. Will had better come up with some good explanations, I thought, as I pulled into the Rensselaer County Jail where he was being held—

Only he wasn't there anymore. Not even eleven-thirty yet, but he was already out on bail. I guess that's one perk to being a lawyer: when you get in trouble yourself, you know which strings to pull.

I got back in my car and drove out to Will's home outside Coxsackie, down below Albany. Coxsackie isn't the world's most happening town; in fact, the state prison is their main employer. But Will's house itself is charming, a rambling old Victorian on a hill overlooking the Hudson River. It's the perfect place to put your feet up in front of a crackling fire and read an old P.G. Wodehouse novel.

Not that Will ever did that. He was a Type A guy to the max, who threw himself into his work the same way he was now throwing himself into his political campaign. As the lone in-house attorney for the Hudson-Adirondack Preservation Society, the region's premier environmental organization, he was fully capable of busting his tail eighteen hours a day for seven months straight in order to save some obscure subspecies of dung beetle.

Any time he had left over from work he spent fixing up his house. He was single now, his most recent girlfriend having left him several months ago. He always dated nice women, good marriage material, but they always ended up leaving him. "Going out with Will is like going out with Alvin the Chipmunk on speed," one of them complained to Andrea once.

When I showed up that morning, Will was in the kitchen guzzling coffee and worrying about how much his bail would cost. He'd had to put up his house as collateral to the bail bondsman.

"I spend ten years working on this place," he complained as he waved me inside. "And now that I finally get it like I want it, I'll have to

sell

it and go live in some God-awful studio apartment."

It seemed strange that Will would be so preoccupied with his house when he had a murder accusation hanging over his head. But I guess this was his way to avoid dealing with it. I eyed him closely. Like me, Will was six feet tall and slender with curly black hair, plus the traditional Jewish nose. Often when we were out in public together, someone would mistake us for brothers. "You think I look like this ugly

shnook?”

I'd say huffily to the waitress or whomever, and Will would do the same.

Hopefully we didn't look too alike right now, though, because Will was a total mess. His right cheek gave intermittent involuntary twitches. Half of his hair seemed to be heading toward Oshkosh, while the other half was going to Zanzibar. The bags under his eyes were so big, you could have carried legal briefs in them.

For the past month or two, he'd looked more and more frazzled each time I saw him. At my candidate's coffees, he would toss back three cups of high-test in twenty minutes. Now he looked worse than ever, like the Wild Man of Borneo with a monster hangover. Or like Alvin on 'ludes.

"How you feeling, buddy?" I asked. "How was your night in jail?"

His right cheek twitched again. "Wonderful. My cellmate was Republican. Thinks the Democrats are too soft on crime."

"I hope he'll vote for you anyhow."

"Doubt he'll get the chance. Seems he has this little problem with robbing liquor stores."

"You know such interesting people."

"Yeah, right. If I get convicted, I'll write a book."

We headed for Will's living room, with its bookcases made of sweet-smelling cherry wood and a big bay window revealing the sunny, sparkling river. The walls were covered with nature photos, which Will shot himself while climbing the forty-six high peaks of the Adirondacks. In his typical headstrong way, it wasn't enough for Will to casually take up weekend hiking

—he had to nail every single one of those forty-six peaks.

This morning he and I were feeling our way through a different kind of wilderness, a potentially much more dangerous one. "Will," I said, "you want to tell me what happened last night?"

He groaned. "I'm sure you read all about it on the front page, along with every other voter in the district."

"I'd like to hear it from you."

"Yeah, okay." He gulped down the dregs of his sixteen-ounce mug and began. "Last night I was supposed to do that half-hour debate with the Hack—oh God, now that he's dead, I shouldn't call him the Hack anymore."

"Don't worry about it."

"It's so horrible." He gave two more quick twitches. "See, the debate was supposed to start at nine. But you know how I like to get places early, so I was there by eight-thirty—"

"At the radio station?"

"Right. WTRO."

I nodded. I had resolutely ignored all the debate hype last night, so I could focus on the kids and getting them ready for school, but I knew the story behind the debate. Will had challenged the Hack to debate him, and the Hack felt politically obligated to accept. But he didn't want to risk debating on TV, where a large number of people might actually be watching. Instead he insisted on WTRO, the public radio station down in Troy. That way, even if he screwed up hardly anyone would hear it, since NPR is not exactly the favorite of the masses. Especially in upstate New York.

Will continued. "When I got there, they put me in the green room—you know, the waiting room—and then they left. A few minutes later they brought in the Hack—I mean Jack—and then left again. So me and Jack were stuck alone together."

"Didn't either of you bring campaign workers along?"

"I

didn't. I like having quiet time before a speech or whatever to gather my thoughts. Maybe Jack was the same way, because there we were, just the two of us. It kind of made me sick. Here we were making small talk, but this was a guy that I wanted to beat his brains out." Will flushed. "I mean in the debate, not literally."

"I understand."

"So I went in the bathroom, just off the green room. I figured I'd sit on the toilet for ten minutes and review my notes. Which is what I was doing when I sort of became vaguely aware of conversation in the other room. Jack was saying something like, 'Hi, how you doing?' Then he made this surprised little squeak, like

'Aah.

r

And then all of a sudden . . . there was a gunshot."

Will shuddered. "I was afraid they'd come in the bathroom and shoot me next. It's lucky I had my pants down, because I got the shit scared out of me for real. But then I heard footsteps running away, and I figured it was safe to come out. So I opened the door a crack

—and Jack was lying on the sofa with his head blown off.

"That's how the radio people found me and Jack when they came running in. And they found the gun, too, just lying there. If only the killer took it away with him, then at least I'd have something to back up my story."

"But that's good news. The cops will be able to trace the gun."

Will rubbed his eyes, looking suddenly exhausted. "I heard some cop say the serial numbers were filed off."

"Maybe they'll find fingerprints," I said brightly, trying to cheer him up.

It didn't work. "Yeah, that would be nice," he said gloomily. "But the gun was wiped clean, or else the guy was wearing gloves. That's what the D.A. said at my arraignment when he was outlining their preliminary evidence."

I had a flash of inspiration. "Gunpowder residue," I said, snapping my fingers. "They must've checked your hand for residue."

"They did."

"And they didn't find any, right? So that proves you're innocent."

He shook his head ruefully. "That's what I thought. But it turns out the stuff, the antimony or barium or whatever, can just wash off. Or even rub off. So its absence doesn't prove anything, especially with a sink in the next room."

How aggravating—with all the advances in scientific crime stuff, none of it seemed to be helping Will... at least not yet, anyway. Will's mopiness was catching. I fought it off. "Is it possible someone's trying to frame you?"

"Can't imagine who."

I tried another tack. "Did anyone at the station see somebody running away?"

Will shook his head. "And no one heard anybody, either."

"How about a car? Anyone see a car drive off?"

"Not that I know of."

This didn't sound good. My face must have shown it. "You've got to help me," Will pleaded, "you've got to. If they send me back to that jail, I'll stick my finger in a light socket!"

I patted him on the shoulder. "Don't worry, Shmuck," I reassured him, with much more confidence than I felt. "We'll get this squared away in no time."

And if you believe that, I've got an Internet stock to sell you.

From Will's house I drove to the scene of the crime. I'd been to WTRO once before, when they interviewed me about my movie.

Ah yes, my movie. I should explain about that, and why I was free to traipse around that morning playing Colombo instead of commuting off to some j.o.b. somewhere.

It's like this. After I escaped from grad school at age twenty-four (with an M.F.A. in Playwriting, of all the ridiculous degrees), I spent fifteen years writing artsy,

avant-garde

screenplays that never got produced and artsy,

avant-garde

stage plays that

did

get produced—off-off-Broadway, for audiences of about four people, including me.

But then one day, while sitting at my old pockmarked desk and debating which bills to pay and which to put off, I somehow took it into my head to write an incredibly dumb disaster movie about deadly gas seeping out of the ground after an earthquake and threatening to destroy the entire population of San Francisco.

The Gas that Ate San Francisco

took five weeks to write, it was the worst piece of junk I'd ever done . . . and it made me a million dollars.

Even after the agents, managers, producers, lawyers, tax men, and other bloodsuckers drank their fill, I still wound up with 300K, free and clear. It was so much money, I decided to take some time off and figure out What I Wanted to Do Next with My Life.

That was almost two years ago now, and I still hadn't figured it out. But hey, between a bull stock market and Andrea's salary as a community college professor, that 300K was holding steady. And my extended sabbatical gave me plenty of time to pursue my other interests, like hanging out at the local espresso bar, teaching Creative Writing at the local state prison, and playing

a lot

of baseball with Derek and Bernie.

I had also, much to my surprise, decided to become a Capitalist Landlord. Six months ago I bought the decrepit house next door and began the long process of tearing things down and building them back up again. After a decade and a half of being a brain-driven writer, I thoroughly enjoyed getting down and dirty. I rented the house out last week to three Skidmore College students, and I gave them such an enthusiastic blow-by-blow description of the rehab process that they almost fell asleep standing on their feet. Now whenever they saw me coming they scurried away like rabbits, afraid I'd shower them with yet more vital information about dry rot.