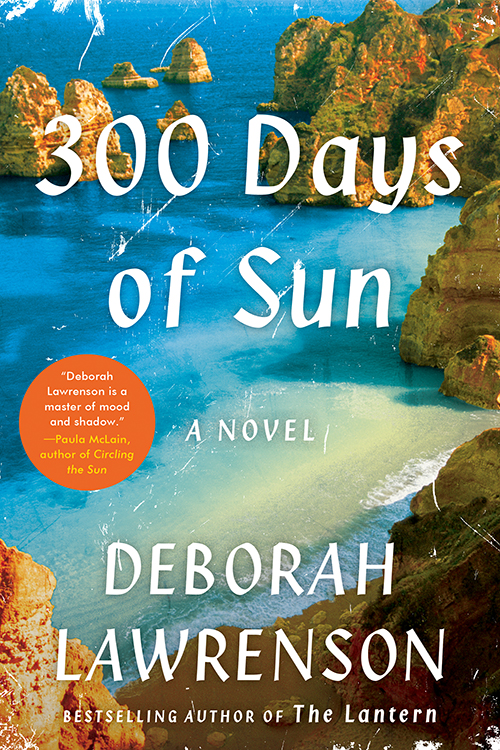

300 Days of Sun

Authors: Deborah Lawrenson

CONTENTS

Â

A

few careless minutes, and the boy was gone.

Violet shadows stretched from the rocks, clock hands over the sand. She shouldn't have allowed herself to linger, but the sea and sky had merged into a shimmering mirror of copper and red; it was hard to tell if she was floating above the water, or standing on air. Waves beat time on the shore then reached out to caress her feet.

She could hear the children shrieking with pleasure. A short distance away, the path threaded up through the rocks to the garden of pine trees and gold coin daisies: Horta das Rochas, the “garden of rocks” near the edge of the world, where famous explorers and navigators once set sail for unknown continents.

Her eyes were still on the dissolving horizon when she called the children. A scampering on the wet sand brought a small hand to her leg. She glanced down.

“Look!” said the girl.

Her daughter pointed to a flock of birds flying in silhouette against a blood-Âorange cloud. They watched for a moment.

“Time to go back,” she said.

The boy, older by a year, spent hours by the rock pool, staring at the stirrings of sea life in miniature. It was no more than a few steps from where she was standing. “Tico!” she called, using his baby name.

No answer.

The rock pool was deserted.

“Where's Tico?”

“Gone,” said the girl.

“He's hiding! Come on.”

She took the girl's hand and they ran to the wind-Âcarved cave. “Tico!”

“Tico!” echoed the girl.

The opening in the rocks was in deep shadow, cold and dark. The girl clutched tighter. They both called again. No answer. They felt along the damp creased walls, for a warm, giggling mass balled up on the ground. The cave was empty. Outside the sunset deepened. They were alone on the beach.

All the way up the path, they called to him. No answer.

The onset of panic froze her in the heat. Why had she not felt the prickle of danger, sensed the change? When she first arrived in this curious country, she had used her skills constantly: patience and observation, subtlety and guile. She needed them, they all had. Vigilance was vital.

She should never have forgotten that the sardine fishermen pulled their boats up from the beach and into the streets for safety when they felt the first intimations of storm swell. The change in atmospheric pressure registered on their skin and in their bones. They trusted their senses and protected themselves because the water could surge right over the walls of the old town fortifications and knock on the door of the cafés.

They knew these seas and storms destroyed houses: waves reached inside and snatched a lifetime's work, floating precious contents out to sea. Boats were smashed into driftwood. Channels vanished; islands were submerged. New inlets were gouged by the wind and the wild rain, redrawing the coastline, making maps obsolete.

But quiet forces were equally destructive. She should never have let down her guard, never forgotten the old threat that remained unseen and insidious.

She began to run.

Â

I

met Nathan Emberlin in Faro, southern Portugal, in August 2014.

At first, I thought he was just another adventurous young man, engaging but slightly immature. His beautiful sculpted face held a hint of vulnerability, but that ready smile and exuberant cheekiness eased his way, as did the radiant generosity of his spirit, so that it wasn't only women who smiled back; Âpeople of all ages warmed to Nathan, even the cross old man who guarded the stork's nest on the lamppost outside the tobacconist's shop.

Yes, he appeared from nowhereâÂbut then, so did we all. I didn't go to Faro to get a story. That summer I was on the run, or so it felt; I was trying to consign an awkward episode to my own past, not to get entangled in someone else's. Besides, a lot of Âpeople I met in Faro were in the process of change, of expanding their horizons and aiming for a better life. The town was full of strangers and constant movement: planes overhead, roaring in and out of the airport across the shore; boats puttering in and out of the harbour; trains sliding between the road and the sea; buses and cars; pedestrians bobbing up and down over the undulating cobblestones.

The café, at least, was still. On the way to the language school, it had the presence and quiet grace of an ancient oak, rooted to its spot in the Rua Dr. Francisco Gomes. The columns and balustrades of its once-Âgrand fin de siècle façade had an air of forgotten romance that was hard to resist. I pushed against its old-Âstyle revolving door that first morning simply because I was curious to see inside.

True to its promise, the interior was cavernous, the ceiling high and elegantly proportioned. But the plaster on the walls was cratered, and mould speckled the cornicing. The tables and chairs were plastic garden furniture, set out haphazardly on a coral-Âand-Âwhite-Âcheckerboard floor; few of them were taken. I went up to the main counter, into an aromatic cloud of strong coffee, where a group of men knotted over an open newspaper. The barman, wiping his hands on an apron that was none too clean, seemed to be engaged in voicing his opinion and was in no hurry to serve me.

Photographs of old Faro were set into wooden panelling: black-Âand-Âwhite scenes of a fishing community, of empty roads and dusty churches. The argument at the bar counter intensified, or that's what it sounded like. It's not always possible to tell in a foreign language. It might just be excitability. But some words were easy to understand.

Contra a natureza. Anorma. Devastador

.

“Bom dia?”

The barman had noticed me at last. There was a sense of a question about his greeting. Or perhaps it was supposed to double for “What would you like?” Four days into

Portuguese for Beginners

, and I could manage to order a cup of coffee. There didn't seem to be anything more substantial for breakfast on display and there were no menus.

The barman pressed some buttons on a brute of a machine, which released a dribble of muddy liquid.

“Bica,”

he said, pushing it towards me in a tiny chipped cup along with a bowl of sugar cubes.

The bill came to pennies. I didn't know this was the Café Aliança.

No, I didn't meet Nathan at the café. At that stage he didn't know any more about the place than I did.

I

t was gone nine o'clock by the time I started the short walk to the language centre. The

calçada

pavement was a mosaic of cobblestones studded with images of fish and wave patterns. It was so uneven that, several times, as I looked up to admire white Moorish-Âstyle buildings against an unbroken blue sky, I experienced a disconcerting drop as the ground fell away beneath me.

I plunged north into a labyrinth of pedestrian streets, away from the tang of salt and boats at anchor. This was always the quietest time of the day. Few shops were open and most Âpeople were only slowly coming round. Nights were late and lively in the town. Faro, like the café, had the air of a once-Âgrand old lady fallen on hard times; too many shops had closed down, empty boxes tied up with ribbons of bill stickers and notices of liquidation. Peeling walls were embossed with election posters from which bland, toothsome faces stared out and made promises on behalf of the Workers' Party and the Communists, and the Man Who Believes in Better for Faro.

The language centre was on the Praça da Liberdade, next to a pharmacy. An illuminated green cross flashed “Go, go, go!” above a small crowd of men and women dressed for business but going nowhere on the pavement outside the entrance to the Centro de Linguas. They watched the closed door with palpable impatience; the lateness with which the morning lessons habitually began was already an issue, particularly with the Swiss and German students, for whom nine o'clock meant nine o'clock.

“

Bom dia,

Joanna,” said one of them now, an IT specialist from Berne.

“

Bom dia,

Tomas

.

”

He looked at his substantial watch and rolled his eyes.

I shrugged. Actually, I was finding the relaxed approach quite restful. The teachers seemed to work hard and offered equal slippage at the end of the day, so nothing was lost.

The door opened at twenty-Âfive past and we filed up the

stairs: two Swiss men, two Germans (a man and a woman), a Belgian woman, a Dutch woman, an Italian man, an Irish man, and me, all professionals and businessÂpeople eager to learn Portuguese. They talked about giving themselves the edge in emerging markets, by which they meant Brazil. Most of them would have gone straight to Rio de Janeiro to learn the language had they been able to afford it. Portugal was cheap, there were three hundred days of sunshine a year, but it was no place to be working unless there was a specific deal to be made.

The owner of the language centre, Senhora Davim, greeted us cheerfully outside the open door of her office. She was a fleshy middle-Âaged woman with pencilled brows and immaculate red lipstick applied over thick foundation. Despite the August heat, she was packed into a dark suit, from which a froth of silky blouse burst when she undid the front buttons.

We took our places in the classroom.

M

y first few days in the country, I was astonished by how many Russian tourists there were here, chattering in the shops and streets. Then I realised: to the uninitiated, Portuguese sounds like Russian. The language is nothing like the soft singsong of Spanish or Italian. The sounds shush and slip around like the shining, sliding cobblestones under your feet.

“Baleia cachalote morta,”

said Caterina, the teacher who took the first morning lesson each day. She was fairly young, though perhaps it was only the untamed frizzy hair that made me think that, along with the large round eyes. Those eyes peered out of her overgrown fringe like a startled lemur's through foliage. She spoke only in Portuguese, which meant we had to concentrate hard.

She held up a newspaper and pointed to the main photograph. It looked like the page the men in the café had been arguing over, and this time I could see what it was: a whale, washed up on a beach.

“A causa da morte da baleia ainda não foi descoberta.”

Caterina enunciated slowly and carefully.

“Remoção da carcaça . . . municÃpio é responsável.”

Cause of death not yet discovered. Removal of the carcass. The municipality was responsible. Caterina pointed to the whale's head. The chain-Âsaw teeth were huge cones, she mimed, each the length of her dark-Âhaired forearm.

The door opened and in sauntered Nathan, wearing ripped jeans. He'd gone native within the first few days as far as timekeeping was concerned. He gave Caterina a salute and flopped into the nearest seat, letting his tatty rucksack drop on the floor.

“

Bom dia,

Nathan.”

“E aÃ, tudo bom?”

Caterina's face always looked tired and her smile rarely lit up her eyes. But she made an exception for Nathan and his slangy greeting (“Hey thereâÂall good?”), especially when he had plenty to say about the beached whale, all in nonstop Portuguese. There had been a terrible storm, or that's what I thought he said, something about devastation on the islands. His conversation might not have been grammatically perfect (I suspected it wasn't) but there was no doubt he was a natural linguist. He was the only other British student and, at twenty-Âfour, the youngest among us.

We moved on to question-Âand-Âanswer exercises taken from a book. After an hour of stilted interrogation about names and jobs and methods of transport (“My name is Enzo; I am from Italy; I work as a company manager; my company makes shoes; I travelled to Faro in a plane.”) we broke for morning coffee in a bar down the road.

Enzo was quite jolly, actually, and wanted to speak English whenever possible. (“Fuck shoes. I want stop shoes. But shoes good for Rio de Janeiro.”) He was in his mid-Âforties, corpulent, hair quite possibly dyed but plenty of it. I sat between him and Nathan and had another tiny coffee along with an almond pastry I justified as a late breakfast.

“You speak Portuguese very good,” Enzo told Nathan.

“Not really, but you've got to have a go, haven't you.”

“Where did you get to last night?” I asked him.

It was fast becoming a standing joke that Nathan's nights were spent drinking and making new friends (we knew he meant girls) at the clubs and bars.

“After O Castelo? The Millennium in Rua do Prior. I met this mad local who said he was a bus driver. I thought he might be good for some free rides. He wanted me to teach him racist abuse in English. I only told him because I'd necked at least six mojitos. I felt awful afterwards.”

Nathan had only been in Faro for a week and he already had a diverse collection of acquaintances. In addition to his encounters with women, he had befriended an Ecuadorian who believed in voodoo and evil spirits and a Spaniard whose idea of punctuality was being only three hours late. Then there were the girls in his lodging house who constantly knocked on his door and had silly, shouty conversations outside in the corridor to make him come out.

He was tanned and rail thin, as if he hardly ate, or rather had got used to not eating if circumstances didn't allow. His cheekbones were sharp, catching the fall of long dark hair and giving a masculine cut to features that might otherwise have been too prettily girlish. He claimed to have flunked normal school somewhere in South London, but he had guts and drive and had travelled around Spain and Portugal, staying three weeks here, one week there. He pronounced the names of the places he has passed through with absolute linguistic accuracy. The course would have been a lot duller without him.

“Nice clean T-Âshirt,” I said, then turned to Enzo. “His landlady is doing his washing for him, free of charge.”

“Couldn't stop her! I feel like I've been adopted. Friendly lot here, aren't they. Credit where it's due.”

“That is because you are friendly,” said Enzo.

“Got to be, haven't you? You should come out one evening, mate. We'll have a laugh.”

Another Âcouple of hours in the plain white rooms of the language centre with its purposeful staff of women. Lunch. Three more hours of listening and trying to speak in response. It was hard work.

Senhora Davim's secretary, a young girl with dyed red hair and a tattoo of a butterfly on her leg, came out of her cubbyhole office as we left to wish us a good evening, shyly, in English. She caught Nathan's eye and looked away quickly when he winked at her. “Cheers, LÃa.”

“You coming to O Castelo this evening?” he asked me as we walked out onto the street. This was the cocktail bar and nightspot on the Old Town wall we'd all been to the first night of the course, when everyone was being sociable. It would be packed on a Friday night.

“Not tonight.”

“What are you up to then?”

“Not much. I'm shattered.”

“See you tomorrow, then. Eleven o'clock at the ferry. You are still going, aren't you? I've asked the others, though I'm not sure how many of them will actually do it.”

“Yes. I'll see you there.”

T

he studio apartment I had rented on Rua da Misericórdia for the six weeks' duration of the language course was on the second floor above a boutique selling hats and beachwear. Across the road stood a fine sixteenth-Âcentury church and, only a few paces away, the Arco da Vila, the arched gateway into the Old Town. I didn't need to use my key to open the faded red entrance door to the side of the shopâÂsomeone had forgotten to close it properly, again. I checked the post box numbered 7. Empty. As I climbed the stone staircase lined with patterned ceramic tiles, my footsteps echoed.

Apart from an air-Âconditioning unit that was losing its battle against the heat, the studio was perfect. It wasn't huge, but not too small either. I've never minded being on my own. In fact, I had been longing to be alone, for these weeks away from Brussels, from Marc and all the complications, while I made up my mind what to do.

From the window was a view of the formal garden behind the marina, the Jardim Manuel Bivar, where old men sat under palm and jacaranda trees in clothes that were too dark, too thick; at the end of the day, elderly women would proceed slowly as the incoming tide to fetch them.

I took a shower to put off the moment I would have to look at my mobile. When I did, there were two missed calls and three texts, tone increasingly angry. With no Wi-ÂFi in the building, I couldn't access any emails. Of course, I could have connected at the language school to download them, but I'd decided to give myself a break.

By eight o'clock the air was soft and tinged with pink from the falling sun. I pulled on jeans, flip-Âflops, and a floaty top and took my iPad off to a bar where I could access the Internet and read some news of the world beyond southern Portugal.

The first evening I was here, I started to notice how most of the streetlamps were tufted with dried grasses and twigs. Then I saw more ragged wigs on church porches and high ledges. I assumed it was yet more evidence of neglect, that weeds had seeded and been left to grow in sandy crevices, but as I began to study them more carefully, I figured it out. They were birds' nests. There was one high on the stone pediment of the gatehouse to the Old Town, a great wheel of grasses, big as a tractor tyre. I looked up as I passed.