33 Days

Authors: Leon Werth

33 DAYS

LÉON WERTH

(1878–1955) was born in Remiremont, France, to a Jewish clothier. Though he was a brilliant student, he dropped out of school to devote himself to writing art criticism, publishing his first critique in the

Paris-Journal

in 1911. His first novel,

The White House

, was a finalist for the Prix Goncourt in 1913. Werth was an anti-bourgeois anarchist, a bohemian, and a leftist Bolshevik supporter. In spite of his politics, however, he was assigned to be a radio operator during World War I, until he was diagnosed with a lung infection and released from service. In 1922, he married Suzanne Canard, and she would later also become active in the Resistance. Werth wrote critically of the Nazi movement and colonialism, became a Gaullist, and contributed to Claude Mauriac’s journal

Liberté de l’Esprit

. In 1931, he was introduced to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry by a mutual friend, and they become extremely close. Saint-Exupéry referred to Werth in three of his books and dedicated two to him. In addition to

33 Days

, Werth also wrote

Déposition

, his journals from 1940 to 1944, while hiding from the Nazis in the Jura Mountains region. He died in Paris on December 13, 1955, at the age of seventy-seven.

ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY

(1900–1944) was a poet, philosopher, aviator, and the author of

The Little Prince

, which has been translated into over 250 languages. His interest in flying inspired him to write

Wind, Sand and Stars

and

Night Flight

. He disappeared over the Mediterranean during a military reconnaissance mission in July 1944.

AUSTIN DENIS JOHNSTON

, a former editor, spent seventeen years at Time, Inc., where he also supervised French and Spanish translations.

THE NEVERSINK LIBRARY

I was by no means the only reader of books on board the

Neversink.

Several other sailors were diligent readers, though their studies did not lie in the way of belles-lettres. Their favourite authors were such as you may find at the book-stalls around Fulton Market; they were slightly physiological in their nature. My book experiences on board of the frigate proved an example of a fact which every book-lover must have experienced before me, namely, that though public libraries have an imposing air, and doubtless contain invaluable volumes, yet, somehow, the books that prove most agreeable, grateful, and companionable, are those we pick up by chance here and there; those which seem put into our hands by Providence; those which pretend to little, but abound in much

.

—

HERMAN MELVILLE,

WHITE JACKET

33 DAYS

Originally published by Viviane Hamy, 1992

Copyright © 1992 by Léon Werth

Translation copyright © 2015 by Austin Denis Johnston

“Lettre à l’ami” copyright © by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

First Melville House printing: April 2015

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Estate of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry for permission to print “Letter to a Friend.”

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com

facebook.com/mhpbooks

@melvillehouse

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Werth, Léon, 1878–1955.

[33 jours. English]

33 days : a memoir / Léon Werth; translated by Austin Denis

Johnston; with [“Letter to a Friend”] by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

pages cm. — (Neversink)

ISBN 978-1-61219-425-7 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61219-426-4 (ebook)

1. Werth, Léon, 1878–1955. 2. Authors, French—20th century—Biography. 3. World War, 1939–1945—Personal narratives, French. 4. World War, 1939–1945—France. I. Saint-Exupéry, Antoine de, 1900–1944. II. Title.

PQ2645.E7A1813 2015

848.91209—dc23

[B]

2015002131

Design by Christopher King

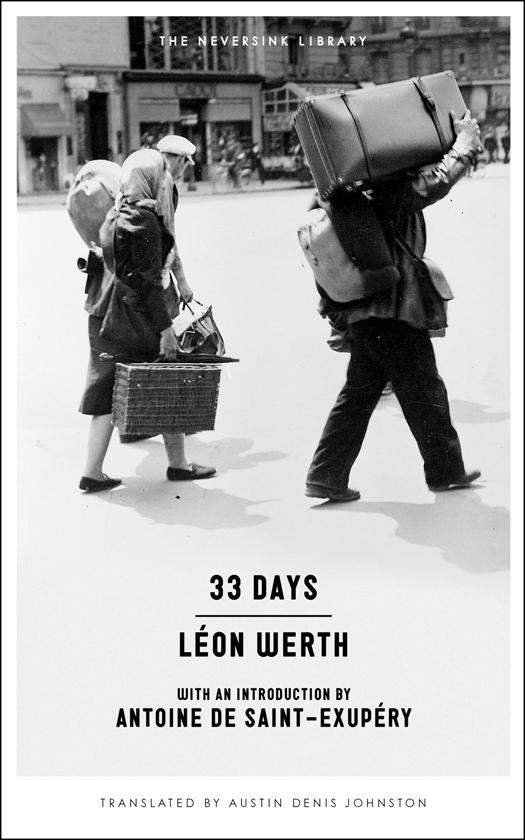

Cover photograph: Exodus, Place de Rome, Paris, June 12–13, 1940.

Courtesy of © Roger-Viollet / The Image Works

Cet ouvrage publié dans le cadre du programme d’aide à la publication bénéficie du soutien du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères et du Service Culturel de l’Ambassade de France représenté aux États-Unis.

This work, published as part of a program of aid for publication, received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Service of the French Embassy in the United States.

v3.1

CONTENTS

Introduction: Letter to a Friend by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

33 Days

Author’s Preface

I: From Paris to Chapelon. The Caravan

II: From Chapelon to the Loire. Battle Scenes

III: Les Douciers. Fifth Column

IV: Chapelon Under the Boot

V: The Colossal Corporal. Return to the Free Zone

EDITOR’S NOTE

This book is based on a manuscript that was smuggled out of Nazi-occupied France in October 1940 by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who took it to New York with the intent of getting the book published in English. But the manuscript—which consisted of his friend Léon Werth’s firsthand account of his escape just months before from Paris, and an introduction to that account written by Saint-Exupéry himself—was never published, and subsequently vanished. Fifty years later, in 1992, Werth’s French-language text was rediscovered and published by the French publisher Viviane Hamy. However, that edition did not include Saint-Exupéry’s introduction, which remained lost. In 2014, the introduction was rediscovered in a Canadian library by Melville House, and thus this book represents not only the first English-language edition of

33 Days

, but the first edition to include both the complete, original text and the introduction, as originally intended by Werth and Saint-Exupéry.

Werth had asked Saint-Exupéry to smuggle the book out of France because, as a Jew, Werth was not allowed by the French government to publish anything. Forced to hide out in France’s Jura Mountains and unable to move about as easily as his non-Jewish friend, Werth also no doubt felt, as did Saint-Exupéry, that an English-language version of his gripping, firsthand testimony might be useful to Saint-Exupéry in his greater mission in going to New York, which was to stir American support for intervention. After all, the story of the massive French flight from the approaching Nazi

Werhmacht

in May and June of 1940—a migration of such biblical proportions as to now be called by historians “

l’Exode

,” or “The Exodus”—was largely unknown in the United States. Werth’s account remains, in fact, one of the few eyewitness documentations of the Exodus, which is estimated to have involved more than eight million people, and to have been the largest mass migration in human history.

In New York, Saint-Exupéry did manage to find an agreeable publisher: Brentano’s, a bookstore that during the war years also published French-language books in translation. Saint-Exupéry asked for nothing more than a military parcel consisting of chocolate, cigarettes, and water purification tablets for payment, and was so certain of the publication that he mentioned

33 Days

in a book of his own published around that time,

Pilote de guerre

. However, for reasons that remain unknown, the book never appeared, and the manuscript was lost. Saint-Exupéry was apparently so frustrated by the failed publication that he took his introduction, at least, and expanded it into another wartime book,

Letter to a Hostage

, with the “hostage” being Werth—who goes unnamed for his protection.

While Werth would survive the war and go on to write numerous books, Saint-Exupéry would not: his plane disappeared while on a reconnaissance mission over the Mediterranean in July 1944, presumably shot down by the Germans.

But

33 Days

, in addition to being a vivid and harrowing firstperson account of one of modern history’s major events, and a welcome introduction in English to an important French writer, stands as a testament to a long-term friendship tempered in wartime, that of Léon Werth and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry—who dedicated his most famous work,

The Little Prince

, to Werth:

I ask children to forgive me for dedicating this book to a grown-up. I have a serious excuse: this grown-up is the best friend I have in the world … He lives in France, where he is hungry and cold. He needs to be comforted.

INTRODUCTION:

LETTER TO A FRIEND

BY ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPÉRY

I.

In December 1940, when I passed through Portugal to go to the United States, Lisbon seemed like a kind of bright, sad haven to me. At the time there was a lot of talk about an imminent invasion. Portugal clung to an appearance of happiness. Lisbon, which had built the most beautiful international exposition in the world, was smiling a weak smile, like that of mothers who’ve had no news of a son at the front and are trying to protect him with their confidence: “My son is alive because I smile …” The same way Lisbon was saying, “Look how happy and peaceful and brightly lit I am …” The entire continent loomed over Portugal like a mountain wilderness, swarming with its packs of hunters. A festive Lisbon defied Europe: “Can I be a target when I make such a point of not hiding! When I’m so vulnerable! When I’m so happy …”

At night my country’s cities were the color of ashes. I’d weaned myself off all light, and this radiant capital gave me a strange uneasiness. If the surrounding neighborhood is dark, the diamonds in a too-brightly lit store window attract prowlers. We feel them circling. I feel Europe’s night, inhabited by shadowy monsters, looming over Lisbon. Perhaps wandering groups of bombers were sniffing at this treasure.

But Portugal ignored the monster’s looming. Ignored it with all its might. Portugal was talking about art with an almost desperate confidence. Would anyone dare destroy it amid its cult of art? It had brought out all its treasures. Would anyone dare destroy it amid its treasures? It showed off its great men. For lack of an army, for lack of cannons, it had marshaled its stone guards—the poets, the explorers, the conquistadors—against the invader’s iron. For lack of an army and cannons, Portugal’s entire past barred the way. Would anyone dare destroy it amid its legacy of a grandiose past?

So every evening I wandered sadly through the triumphs of this exposition of supreme taste, where everything approached perfection, even the music, so discreet, chosen with such delicacy, that flowed gently over the gardens, quietly, like the simple melody of a fountain. Was anyone going to eradicate this marvelous sense of proportion from the world?

And I found Lisbon, with its desperate smile, sadder than my darkened cities.

I’ve known, maybe you have too, those slightly bizarre families that reserved the place at their table of someone who had died. They refused to let death in. But I didn’t see any consolation in that. The dead should be dead. Then, in their role as dead, they find a different kind of presence. But these families postponed their return. They changed them into eternal absentees, into friends late for eternity. They traded mourning for a meaningless waiting. And to me these households seemed plunged into an unremitting malaise that was sad in a way different than sorrow. Guillaumet, the last friend I lost, who was shot down flying mail service into Syria, I count him as dead, by God. He’ll never change. He’ll never be here again, but he’ll never be absent either. I removed his place setting from my table—a useless trap that didn’t snare him—and I made him a truly dead friend.