(5/20)Over the Gate (2 page)

To my surprise, the door opened quickly and quietly, showing an elegant white-painted hall and staircase. Mrs Hurst greeted me politely.

'I wondered if your husband—' I began diffidently.

'Come in,' she smiled, and I followed her into the drawing-room on the right-hand side of the corridor. The sight that greeted me was so unexpected that I almost gasped. Instead of the gloomy interior which I had imagined would match Laburnum Villa's unlovely exterior I found a long light room with a large window at each end, one overlooking the front, and the other the back garden. The walls were papered with a white-striped paper and the woodwork was white to match. At the windows hung long velvet curtains in deep blue, faded but beautiful, and a square carpet echoed the colour. Each piece of furniture was fine and old, shining with daily polishing by a loving hand.

But by far the most dominating feature of the room was a large portrait in oils of a black-haired man dressed in clothes of the early nineteenth century. It was not a handsome face, but it showed strength of character and kindliness. Surrounded by an ornate wide gold frame it glowed warmly above the white marble fireplace.

'What a lovely room!' I exclaimed.

'I'm glad you like it,' replied Mrs Hurst. 'My husband and I got nearly everything here at sales. We go whenever we can. It makes a day out and we both like nice things. Our landlord let us have the wall down between these two rooms, so that it's made one good long one, which is a better shape than before, and much lighter too.'

I nodded appreciatively.

'Sit down, do,' she continued. Til get Fred. We live at the back mostly, and I'll tell him you're here.'

I waited in an elegant round armchair with a walnut rim running round its back, and gazed at this amazing room. What a contrast it was, I thought, to Mrs Pratt's counterpart at Jasmine Villa! There the room was crowded with a conglomeration of furniture, from bamboo to bog oak, each hideous piece bearing an equally hideous collection of malformed pottery. That was, to my mind, the most distracting room in Fairacre, whereas this was perhaps the most tranquil one I had yet encountered.

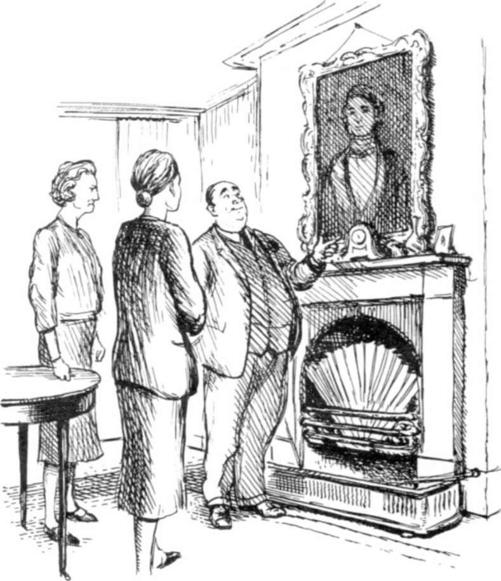

Fred Hurst returned with his wife. He was short while she was tall, rosy while she was pale; and certainly more inclined to gossip than his dignified wife. He examined my trivet carefully.

'Nice little piece,' he said admiringly. 'A good hundred years old. I can mend it so as you'll never know it was broken.'

He told me that he could get it done in a week, and we talked generally about our gardens and the weather for a little while before I rose to go.

'I envy you this room,' I said truthfully. 'The school house has tiny rooms and furniture always looks so much better with plenty of space for it.'

'Pictures too,' added Fred Hurst. He pointed to the portraits. 'One of my ancestors,' he continued.

I heard Mrs Hurst draw in her breath sharply.

'Fred!' she said warningly. Her husband looked momentarily uncomfortable, then moved towards me with hand outstretched.

'We mustn't keep you, Miss Read,' he said politely. Til do my best with the trivet.'

I made my farewells, promised to return in a week, and walked to the gate. There I turned to wave to Mrs Hurst who stood regally still upon her doorstep. She wore upon her pale face such an expression of stony distaste that I forebore to raise my hand, but set of soberly for home.

What in the world, I asked myself in astomshment, had happened in those few minutes to make Mrs Hurst look like that?

A week later, in some trepidation, I called again. Somewhat to my relief, only Fred Hurst was at home. He took me into the charming drawing-room again and lifted my mended trivet from a low table. The repair had been neatly done. It was clear that he was a clever workman.

'My wife's gone down to the shop,' he said. 'She'll be sorry to miss you.'

I murmured something polite and began to look in my purse for the modest half crown which was all that he charged for his job.

'She doesn't see many people, living down here,' he went on. 'Bit quiet for her, I think, though she don't complain. I'm the one that likes company more, you know. Take after my old great-great-grandad here.'

He waved proudly at the portrait. The dark painted eyes seemed to follow us about the room.

'A very handsome portrait,' I commented.

'A fine old party,' agreed Fred Hurst, smiling at him. 'Had a tidy bit of money too, which none of us saw, I may say. Ran through it at the card table, my dad told me, and spent what was left on liquor. They do say, some people, that he had some pretty wild parties, but you don't have to believe all you hear.'

It was quite apparent that Fred Hurst's ancestor had a very soft place in his descendant's heart. He spoke of his weaknesses with indulgence, and almost with envy, it. seemed to me. Certainly he was fascinated by the portrait, returning its inscrutable gaze with an expression of lively regard.

I could hear the sound of someone moving about in the kitchen, but Mr Hurst, engrossed as he was, seemed unaware of it.

'I should like to think I took after him in some ways,' he continued boisterously. 'He got a good deal out of life, one way and another, did my old great-great-grandad.'

The door opened and Mrs Hurst swept into the room like a chilly wind.

'That'll do, Fred,' she said quenchingly. 'Miss Read don't want to hear all those old tales.' She bent down to pick an imaginary piece of fluff from the carpet. I could have sworn that she wanted to avoid my eyes.

'Your husband has mended my trivet beautifully,' I said hastily. 'I was just going.'

'I'll come to the gate with you,' said Mrs Hurst more gently. We made our way down the sloping path to the little lane.

'My husband enjoys a bit of company,' she said, over the gate. 'I'm afraid he gets carried away at times. He dearly likes an audience.' She sounded apologetic and her normally pale face was suffused with pink, but whether with shame for her own tartness to him or with some secret anger, I could not tell. Ah well, I thought, as I returned to the school house, people are kittle-cattle, as Mr Willet is fond of reminding me.

'A pack of lies,' announced Mrs Pringle forthrightly when I mentioned Mr Hurst's portrait. 'That's no more his great-great-grandad than the Duke of Wellington!'

'Fred Hurst should know!' I pointed out mildly. I knew that this was the best way of provoking Mrs Pringle to further tirades and waited for the explosion.

'And so he does!' boomed Mrs Pringle, her three chins wobbling self-righteously. 'He knows quite well it's a pack of lies he's telling—that's when he stops to consider, which he don't. That poor wife of his,' went on the lady, raising hands and eyes heavenward, 'what she has to put up with nobody knows! Such a god-fearing pillar of truth as she is too! Them as really knows 'em, Miss Read, will tell you what that poor soul suffers with his everlasting taradiddles.'

'Perhaps he embroiders things to annoy her,' I suggested. 'Six of one and half-dozen of the other, so to speak.'

'Top and bottom of it is that he don't fairly know truth from lies,' asserted Mrs Pringle, brows beetling. 'This picture, for instance, everyone knows was bought at Ted Purdy's sale three years back. It's all of a piece with Fred Hurst's goings-on to say it's a relation. He starts in fun, maybe, but after a time or two he gets to believe it.'

'If people know that, then there's not much harm done,' I replied.

Mrs Pringle drew an outraged breath, so deeply and with such volume, that her stout corsets creaked with the strain.

'Not much harm done?' she echoed. 'There's such a thing as mortal sin, which is what plain lying is, and his poor wife knows it. My brother-in-law worked at Sir Edmund's when the Hursts was there and you should hear what went on between the two. Had a breakdown that poor soul did once, all on account of Fred Hurst's lies. "What'll become of you when you stand before your Maker, Fred Hurst?" she cried at him in the middle of a rabbit pie! My brother-in-law saw what harm lying does all right. And to the innocent, what's more! To the innocent!'

Mrs Pringle thrust her belligerent countenance close to mine and I was obliged to retreat.

'Yes, of course,' I agreed hastily. 'You are quite right, Mrs Pringle.'

Mrs Pringle sailed triumphantly towards the school kitchen with no trace of a limp. Victory always works wonders with Mrs Pringles bad leg.

In the weeks that followed I heard other people's accounts of the tension which existed between volatile Fred Hurst and his strictly truthful wife. It was only this one regrettable trait evidently in the man's character which caused unhappiness to Mrs Hurst. In all other ways they were a devoted couple.

'I reckons they're both to be pitied,' said Mr Willet, our school caretaker one afternoon. He was busy at the never-ending job of sweeping the coke into its proper pile at one end of the playground. Thirty children can spread a ton of coke over an incredibly large area simply by running up and down it. Mr Willet and I do what we can by exhortation, threats, and occasional cuffs, but it does not seem to lessen his time wielding a stout broom. Now he rested upon it, blowing out his ragged grey moustache as he contemplated the idiosyncrasies of his neighbours.

'They've both got a fault, see?' he went on. 'He tells fibs. She's too strict about it. But she ain't so much to blame really when you know how she was brought up. Her ol' dad was a Tartar. Speak-when-you're-spoken-to, Dad's-always-right sort of chap. Used to beat the livin' daylights out o' them kids of his. She's still afeared that Fred'll burn in hell-fire because of his whoppers. I calls it a tragedy, when you come to think of it.'

He returned to his sweeping, and I to my classroom. I was to remember his words later.

Time passed and the autumn term was more than half gone. The weather had been rough and wet, and the village badly smitten with influenza. Our classes were small and there were very few families which had escaped the plague. Fred Hurst was one of the worst hit, Mrs Pringle told me.

It was some months since the incident of the trivet and I had forgotten the Hursts in the press of daily affairs. Suddenly I remembered that lovely room, the portrait, and the passions it aroused.

'Very poorly indeed,' announced Mrs Pringle, with lugubrious satisfaction. 'Doctor's been twice this week and Ted Prince says Fred's fallen away to a thread of what he was.'

'Let's hope he'll soon get over it,' I answered briskly, making light of Mrs Pringle's dark news. One gets used to believing a tenth of all that one hears in a village. To believe everything would be to sink beneath the sheer weight of all that is thrust upon one. Seeing my mood Mrs Pringle swept out, her leg dragging slightly.

At the end of that week I set off for Caxley. It was a grey day, with the downs covered in thick mist. The trees dripped sadly along the road to the market town, and the wet pavements were even more depressing. My business done, I was about to drive home again when I saw Mrs Hurst waiting at the bus stop. She was clutching a medicine bottle, and her face was drawn and white.

She climbed in gratefully, and I asked after her husband. She answered in a voice choked with suppressed tears.

'He's so bad, miss, I don't think he'll see the month out. Doctor don't say much, but I know he thinks the same.'

I tried to express my shock and sympathy. So Mrs Pringle had been right, I thought, with secret remorse.

'There seems no help anywhere,' went on the poor woman. She seemed glad to talk to someone and I drove slowly to give her time. 'I pray, of course,' she said, almost perfunctorily. 'We was all brought up very strict that way by my father. He was a lay preacher, and a great one for us speaking the truth. Not above using the strap on us children, girls as well as boys, and once, I remember, he made me wash my mouth out with carbolic soap because he said I hadn't told the truth. He was wrong that time, but it didn't make no difference to dad. He was a man that always knew best.'

She sighed very sadly and the bottle trembled in her fingers.

'He never took to Fred, nor Fred to him; but there's no doubt my dad was right. There's laws laid down to be kept and them that sin against them must answer for it. "As ye sow, so shall ye reap," it says in the Bible, and no one can get over that one.'

She seemed to be talking to herself and I could do nothing but make comforting noises.

'Fred's the best husband in the world,' she continued, staring through the ram spattered windscreen with unseeing eyes, 'but he's got his failings, like the rest of us. He don't seem to know fact from fancy, and sometimes I tremble to think what he's storing up for himself. I've reasoned with him—I've told him straight—I've always tried to set him an example—.'

Her voice quivered and she fell silent. We drove down the village street between the shining puddles and turned into the lane leading to the misty downs. I stopped the car outside Laburnum Villas. It was suddenly very quiet. Somewhere nearby a rivulet of rainwater trickled along unseen, hidden by the dead autumn grasses.

'You see,' said Mrs Hurst, 'I've never told a lie in my life. I can't do it—not brought up as I was. It's made a lot of trouble between Fred and me, but it's the way I am. You can't change a thing like that.'