59 Seconds: Think a Little, Change a Lot (20 page)

Read 59 Seconds: Think a Little, Change a Lot Online

Authors: Richard Wiseman

Tags: #Psychology, #Azizex666, #General

Interestingly, it seems that gestures that reflect a form of escapism and surprise top the list, followed by those that reflect thoughtfulness, with blatant acts of materialism trailing in last place—scientific evidence, perhaps, that when it comes to romance, it really is the thought that counts.

FIVE TO ONE: WHEN WORDS SPEAK LOUDER THAN ACTIONS

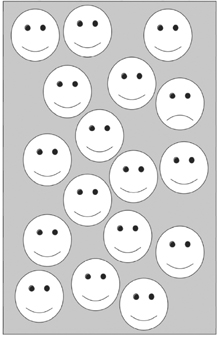

Try to spot the unhappy face in the diagram below.

For most people, the task is surprisingly easy, with the unhappy face seeming to jump out from the crowd. Research shows that, conceptually speaking, the same effect influences many aspects of our everyday lives. Negative events and experiences are far more noticeable and have a greater impact on the way we think and behave than their positive counterparts.

5

Put people in a bad mood, and they can easily remember negative life events, such as the end of a relationship or being laid off, but cheer them up, and they find it far harder to recall their first kiss or their best vacation. A single act of

lying or dishonesty often has a disproportionate effect on a person’s reputation and can quickly undo the years of hard work that have gone into building up a positive image.

American humorist Helen Rowland once noted, “A woman’s flattery may inflate a man’s head a little, but her criticism goes straight to his heart, and contracts it so that it can never again hold quite so much love for her.” This seems to make intuitive sense, but are these assertions supported by findings from modern-day science?

As discussed earlier, psychologist John Gottman has spent more than thirty years exploring the key factors that predict whether a couple will stick together or drift apart.

6

Much of his work has involved examining the comments made by couples when they chat with each other about their relationship. Over the years he has become especially interested in the role played by positive comments (reflecting, for example, agreement, understanding, or forgiveness) and negative ones (involving hostility, criticism, or contempt). By carefully recording the frequency of these, and then tracking the success of the relationship, Gottman was able to figure out the ratio of positive to negative comments that predicted the downfall of a partnership. His findings make fascinating reading and firmly endorse the thoughts of Dale Carnegie. For a relationship to succeed, the frequency of positive comments has to outweigh negative remarks by about five to one. In other words, it takes five instances of agreement and support to undo the harm caused by a single criticism.

Unfortunately, Gottman’s work also revealed that the much-needed positive comments are surprisingly thin on the ground. Why should this be the case? Once again, a detailed analysis of couples’ conversations revealed the answer. When one person made a supportive remark (“Nice tie”), their partner

tended

to respond with a positive comment of their own

(“Thanks. Nice dress”). However, the pattern was far from reliable, and an entire succession of positive remarks (“Nice tie, and really like your shirt, and lovely sweater, too”) often failed to produce a single pleasant reply. In contrast, the response to negative comments was far more predictable, with the smallest of criticisms (“Are you sure about that tie?”) often provoking a hail of negativity (“Well, I like it even if you don’t. And why should I care what you think about my tie? It’s not as if you have the best dress sense in the world. I mean, take that dress. You look like a scarecrow that has let itself go. That’s it, I am out of here”).

Gottman’s work shows that relationships thrive and survive on mutual support and agreement, and that even the briefest of bitter asides needs to be sweetened with a great deal of love and attention. Unfortunately, conversational conventions do not encourage these much-needed compliments and supportive comments.

Having partners monitor and modify the language that they use when they speak to each other is difficult and would require a relatively large amount of time and effort. However, the good news is that researchers have discovered quick, but nevertheless effective, ways of using words to improve relationships.

Take, for example, work by psychologists Richard Slatcher and James Pennebaker at the University of Texas at Austin.

7

Slatcher and Pennebaker knew that previous research suggested that having people who have experienced a traumatic event write about their thoughts and feelings helped prevent the onset of depression and enhanced their immune system. They wondered if it could also improve the quality of people’s relationships. To find out, they recruited more than eighty newly formed couples and randomly assigned one member of each couple to one of two groups. Those in one group were

asked to spend twenty minutes a day for three consecutive days writing about their thoughts and feelings concerning their current relationship. In contrast, those in the other group were asked to spend the same amount of time writing about what they had been up to that day. Three months later the researchers contacted all of the participants and asked them whether their relationship was still ongoing. Remarkably, the simple act of having one member of the relationship write about their feelings for their partner had had a significant effect. Of those who had engaged in such “expressive” writing, 77 percent were still dating their partners, compared to just 52 percent of those who had written about their daily activities.

To explore what lay behind this dramatic difference, the researchers collected and analyzed the text messages that the couples had sent to each other during the three-month assessment period. By carefully counting all of the positive and negative words in the messages, they discovered that the texts from those who had carried out the expressive writing exercise contained significantly more positive words than the messages from those who had written about their daily lives. In short, the results demonstrated how a seemingly small activity can have a surprisingly large impact. Spending just twenty minutes a day for three days writing about their relationship had a long-term impact, both on the language that they used to communicate with their partner and on the likelihood that they would stick together.

Other research has suggested that it doesn’t even take twenty minutes a day for three days to improve the health of your relationship. Take a look at the following illustration.

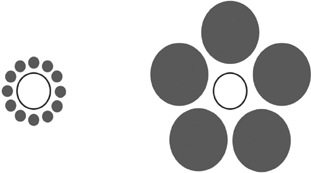

The white circle on the left appears to be larger than the white circle on the right. In fact, the two circles are identical, but they appear to be different sizes because our brains automatically compare each of the circles to their surroundings. The left circle is surrounded by small circles and so, in comparison, appears to be relatively large. In contrast, the right circle is surrounded by large circles and therefore appears to be relatively small.

Bram Buunk, at the University of Groningen and his colleagues from other universities, wondered whether the same type of “comparative thinking” could be used to enhance the way people viewed their relationships.

8

To find out, Buunk recruited participants who were in long-term relationships and asked them to think about their partner in one of two ways. One group was simply asked to jot down a few words explaining why they thought their relationship was good. In contrast, a second group was asked to first think about other relationships that they believed were not as good as their own and then write why theirs was better. Conceptually, the second group’s task was similar to the situation on the left side of the illustration. As predicted, by mentally surrounding their relationship with smaller circles, participants felt far more positive about their partner.

Finally, work by psychologists Sandra Murray and John Holmes suggests that even one word can make all the difference.

9

In their study, people were interviewed about their partner’s most positive and negative qualities. The research team then followed participants for a year, monitoring which relationships stayed the course and which fell by the wayside. They next examined the different types of language that the people in the successful and unsuccessful relationships had used during the interview. Perhaps the most important difference came down to just one word—“but.” When talking about their partner’s greatest faults, those in successful relationships tended to qualify any criticism. Her husband was lazy, but that gave the two of them reason to laugh. His wife was a terrible cook, but as a result they ate out a lot. He was introverted, but he expressed his love in other ways. She was sometimes thoughtless, but that was due to a rather difficult childhood. That one simple word was able to help reduce the negative effect of their partner’s alleged faults and keep the relationship on an even keel.

IN 59 SECONDS

The following three-day task is similar to those used in experimental studies showing that spending time writing about a relationship has several physical and psychological benefits and can help improve the longevity of the relationship.

DAY 1

Spend ten minutes writing about your deepest feelings about your current romantic relationship. Feel free to explore your emotions and thoughts.

DAY 2

Think about someone that you know who is in a relationship that is in some way inferior to your own. Write three important reasons why your relationship is better than theirs.

DAY 3

Write one important positive quality that your partner has, and explain why this quality means so much to you.

Now write something that you consider to be a fault with your partner (perhaps something about his or her personality, habits, or behavior), and then list one way in which this fault could be considered redeeming or endearing.

A ROOM WITH A CUE

Imagine that you have just walked into the living room of a complete stranger. You know nothing about the person and have just a few moments to look around and try to understand something about their personality. Take a look at those art prints on the walls and the photographs above the fireplace. Notice how books and CDs are scattered all over the place—what does that tell you? Do you think that the person living here is an extrovert or an introvert? An anxious person or someone who is more relaxed about life? Are they in a relationship and, if so, are they genuinely happy with their partner? Okay, time to leave. The fictitious owner is coming back soon, and if they find you here they will be furious.

Psychologists have recently started to take a serious interest in whether it is possible to tell something about a person’s personality and relationships from their homes and offices. For example, a few years ago, Sam Gosling at the University of Texas at Austin arranged for people to complete standard personality questionnaires. Then he sent a team of trained observers to carefully record many aspects of their living and work spaces.

10

Were the rooms cluttered or well organized? What kinds of posters did they have on the wall? Did they have potted plants and, if so, how many? The research showed that, for example, the bedrooms of creative people did not have any more books and magazines than the bedrooms of others, but their reading matter was drawn from a greater variety of genres. Likewise, when it came to the workplace, extroverts’ offices were judged as warmer and more inviting than those of their introverted colleagues. Gosling concluded that many aspects of people’s personality were reflected in their surroundings.

Other work has examined what you can tell about a person’s relationship from their surroundings. Time for another exercise. This one really works only if you are currently in a relationship, so you will have to sit it out if you are single. Sorry about that. On the plus side, it is quite quick, so you won’t have long to wait.

First, decide which room in your house you tend to use to entertain guests. Okay, now imagine sitting in the middle of that room and looking around (of course, if you happen to be in the room, simply look around). On a piece of paper, make a list of your five favorite objects in the room. This can include posters, art prints, tables, chairs, sculptures, potted plants, toys, gadgets—anything that really appeals to you. Next, think about how you acquired each object on the list. If your partner bought the object, or it was a joint purchase, place a checkmark beside it. You should end up with a list of five objects and between zero and five checkmarks.