59 Seconds: Think a Little, Change a Lot (27 page)

Read 59 Seconds: Think a Little, Change a Lot Online

Authors: Richard Wiseman

Tags: #Psychology, #Azizex666, #General

If that doesn’t work, you could always try a technique investigated by Justin Kruger and Matt Evans at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

28

In their studies, participants estimated how long it would take to carry out a relatively complicated activity, such as getting ready for a date. One group was asked simply to make their estimates, while another group was encouraged to “unpack” the activity into its constituent parts (showering, changing clothes, panicking) before deciding on a time frame. Those who did the mental unpacking exercise produced estimates that proved far more accurate than those of other participants. So to find out how long it really will take you to do something, isolate all of the steps involved and then make your time estimate.

parenting

The Mozart

myth

,

how to choose the

best name

for a baby,

instantly

divine a child’s destiny using

just three marshmallows, and

effectively

praise

young minds

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

was born in 1756, composed some of the world’s greatest classical music, and died, probably of acute rheumatic fever, in 1791. He was a genius. However, some believe that his music is able to reach parts of the brain that other compositions can’t and that it can make you more intelligent. Moreover, they seem convinced that this effect is especially powerful for young, impressionable minds, recommending that babies be exposed to a daily dose of Mozart for maximum impact. Their message has spread far and wide—but is it really possible to boost a youngster’s brainpower using the magic of Mozart?

In 1993 researcher Frances Rauscher and her colleagues at the University of California published a scientific paper that changed the world.

1

They had taken a group of thirty-six college students, randomly placed them in one of three groups, and asked each group to carry out a different ten-minute exercise. One group was asked to listen to Mozart’s Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, the second group heard a standard relaxation tape, and the third group sat in complete silence. After the exercise, everyone completed a standard test designed to measure one aspect of intelligence, namely the ability to manipulate spatial information mentally (see illustration on the following page). The results revealed that those who had listened to Mozart scored significantly higher than those who heard the relaxation tape or sat in complete silence. The

authors also noted that the effect was only temporary, lasting between ten and fifteen minutes.

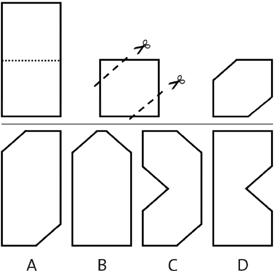

The type of item that might appear in a test measuring the ability to manipulate spatial information mentally. The top row shows a piece of paper being folded in half and then having two pieces cut away. Participants are asked to look at the four shapes on the bottom row and choose the shape they would see when they unfolded the cut paper

.

Two years later, the same researchers followed up their initial study with a second experiment that involved a larger group of students and took place over the course of several days.

2

The students were again randomly placed in one of three groups. In the first part of the experiment, one group listened to Mozart, another group sat in silence, and a third heard a Philip Glass track (“Music with Changing Parts”). Again, strong differences emerged, with those who listened to Mozart outperforming the other two groups in a further test of mental paper folding. On later days, the Philip Glass track

was replaced with an audiotaped story and trance music. Now, the Mozart and the silence groups obtained almost identical scores, while those who listened to the story or the trance music trailed in third place. The evidence suggested that Mozart’s music might have a small, short-term effect on one aspect of intelligence.

Journalists soon started to report the findings.

New York Times

music critic Alex Ross suggested (no doubt with his tongue firmly in his cheek) that they had scientifically proven that Mozart was a better composer than Beethoven. However, some writers soon started to exaggerate the results, declaring that just a few minutes of Mozart resulted in a substantial and long-term increase in intelligence.

The idea spread like wildfire, and during the latter half of the 1990s the story mutated even further from the original research. Up to that point, not a single study had examined the effect of Mozart’s music on the intelligence of babies. However, some journalists, unwilling to let the facts get in the way of a good headline, reported that babies became brighter after listening to Mozart. These articles were not isolated examples of sloppy journalism. About 40 percent of the media reports on the alleged “Mozart” effect published toward the end of the 1990s mentioned this alleged benefit to babies.

3

The continued popular media coverage of what was now being labeled the “Mozart” effect even impinged on social policy. In 1998 the State of Georgia supported the distribution of free CDs containing classical music to mothers of newborns, and the state of Florida passed a bill requiring state-funded day-care centers to play classical music on a daily basis.

The alleged “Mozart” effect had been transformed into an urban legend, and a significant slice of the population incorrectly believed that listening to Mozart’s music could help

boost all aspects of intelligence, that the effects were long-lasting, and that even babies could benefit. However, as the 1990s turned into the twenty-first century, the situation went from bad to worse.

First, Christopher Chabris at Harvard University collected the findings from all of the studies that had attempted to replicate Rauscher’s original results and concluded that the effect, if it existed at all, was much smaller than had originally been thought.

4

Then other work suggested that even if it did exist, the effect may have nothing to do with the special properties of Mozart’s Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, and could in fact be associated with the general feelings of happiness produced by this type of classical music. For example, in one study researchers compared the effects of Mozart’s music with those of a much sadder piece (Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor for Organ and Strings), and found evidence that, once again, Mozart had more of an effect than the alternative.

5

However, when the research team conducted a control experiment about how happy and excited the music made participants feel, the alleged “Mozart” effect suddenly vanished. In another study, psychologists compared the effect of listening to Mozart with that of hearing an audiotape of Stephen King’s short story “The Last Rung on the Ladder.”

6

When participants preferred Mozart to King, their performance on the mental manipulation task was better than when listening to the piano concerto. However, when they preferred King to Mozart, they performed better after they had heard his story.

The public’s belief about the alleged “Mozart” effect is a mind myth. There is almost no convincing scientific evidence to suggest that playing his piano concertos for babies will have any long-term or meaningful impact on their intelligence. Would it be fair to conclude that there is no way of

using music to boost children’s intelligence? Actually, no. In fact, evidence for the benefits of music exists, but it involves throwing away the Mozart CDs and adopting a more hands-on attitude.

Some research has shown that children who attend music lessons tend to be brighter than their classmates. However, it is difficult to separate correlation from causation. It could be that having music lessons makes you brighter, or it could be that brighter or more privileged children are more likely to take music lessons. A few years ago, psychologist Glenn Schellenberg decided to carry out a study to help settle the matter.

7

Schellenberg started by placing an advertisement in a local newspaper, offering free weekly arts lessons to six-year-old children. The parents of more than 140 children replied, and each child was randomly assigned to one of four groups. Three of the groups were given lessons over the course of several months at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, while the fourth group acted as a control group and didn’t receive lessons until after the study had ended. Of those who attended the lessons, one-third were taught keyboard skills, another third were given voice training, and the final third went to drama classes. Before and after their lessons, all of the children completed a standard intelligence test.

The results showed clear IQ improvements in children who had been taught keyboard skills and given voice lessons, whereas those given drama lessons were no different than the control group. Why should this be the case? Well, Schellenberg believes that learning music involves several key skills that help children’s self-discipline and thinking, including long periods of focused attention, practicing, and memorization.

Whatever the explanation, if you want to boost the brainpower

of your offspring, perhaps it is time to take that Mozart CD out of the player and get the kids to start tickling the ivories themselves.

PLAYING THE NAME GAME

Parents often find it surprisingly difficult to decide what to call their baby, in the knowledge that their child is going to spend his or her entire life living with the consequences of their choice. Research suggests that they are right to give the issue careful thought; a large body of work shows that people’s names can have a sometimes powerful effect.

For example, in one of my previous books,

Quirkology

, I described work suggesting that when it comes to where people choose to live, there is an overrepresentation of people called Florence living in Florida, George in Georgia, Kenneth in Kentucky, and Virgil in Virginia.

8

Also, in terms of marriage partners, research has revealed that more couples share the same letter of their family name than is predicted by chance. It is even possible that people’s political views are, to some extent, shaped by their names. Research on the 2000 presidential campaign indicated that people whose surnames began with the letter

B

were especially likely to make contributions to the Bush campaign, whereas those whose surnames began with the letter

G

were more likely to contribute to the Gore campaign.

Since then, I have conducted additional work that has uncovered other ways in which your surname might influence your life. I recently teamed up with Roger Highfield, then science editor of the

Daily Telegraph

, to discover whether people who had a surname that began with a letter toward the start of the alphabet were more successful in life than those

with names starting with letters toward the end. In other words, are the Abbotts and Adamses of the world likely to be more successful than the Youngs and the Yorks?

There was good reason to think that there may indeed be a link. In 2006 American economists Liran Einav and Leeat Yariv analyzed the surnames of academics working in economics departments at U.S. universities and found that those whose initials came early in the alphabet were more likely to be in the best-rated departments, become fellows of the Econometric Society, and win a Nobel Prize.

9

Publishing their remarkable findings in

the Journal of Economic Perspectives

, they argued that “alphabetical discrimination” probably resulted from the typical practice of alphabetizing the names of authors of papers published in academic journals, which meant that those with names toward the beginning of the alphabet appeared more prominent than their alphabetically challenged peers.

I wondered whether the same effect might apply outside the world of economics. After all, whether on a school register, at a job interview, or in the exam hall, those whose surnames fall toward the start of the alphabet are accustomed to being put first. We also often associate the top of a list with winners and the bottom with losers. Could all of these small experiences accumulate to make a long-term impact?

Everyone participating in the experiment stated their sex, age, and surname, then rated how successful they had been in various aspects of their life. The results revealed that those with surnames that started with letters toward the beginning of the alphabet rated themselves more successful than those whose names started with later letters. The effect was especially pronounced in career success, suggesting that alphabetical discrimination is alive and well in the workplace.

What could account for this strange effect? One pattern in

the data provided an important clue. The surname effect increased with age, giving the impression that it was not the result of childhood experiences but a gradual increase over the years. It seems that the constant exposure to the consequences of being at the top or bottom of the alphabet league slowly makes a difference in the way in which people see themselves. So should these results give those whose surname initial falls toward the end of the alphabet cause for concern? As a Wiseman, and therefore someone with a lifetime’s experience of being near the end of alphabetical lists, I take some comfort from the fact that the effect is theoretically fascinating but, in practical terms, very small.