(7/20) Fairacre Festival (8 page)

Read (7/20) Fairacre Festival Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #Country life, #Fairacre (England: Imaginary Place), #Fairacre (England : Imaginary Place), #Festivals

A jagged flash split the sky, to be followed by another reverberating thunder clap.

'It's further off,' said someone hopefully.

'You wants to count, one, two, three, four, see? As soon as the lightning comes you starts counting and sees how many you gets to afore the thunder bangs out. That'll tell you how many miles off the storm be!'

I recognised the voice of this young know-all as Ernest, my Swineherd-Prince.

'You speak when you're spoken to,' said his mother, in a scandalised whisper. 'Piping up like that, and in church, too!'

A few scurrying figures flitted about the shadows bearing candles. There was a medieval beauty about their downbent heads and their curved hands sheltering the precious tiny flames from any draught, which was poignantly in keeping with the ancient building.

'Mr Annett,' announced the vicar, 'will play some music by Bach while we wait.'

We settled back against the hard pew-backs and let the sonorous chords flow over us. How many of our Fairacre forbears, I wondered, had listened to Bach by candlelight, as we were doing now? My mind began to wander. There was something wonderfully comforting in the thought that we shared so much in this building with those longdead and those yet unborn. We were, after all, simply a link in a long chain stretching back for centuries and forward into eternity.

The candle flames stretched and wavered in the draught. A rumble of thunder rattled over the roof.

'I told you so,' whispered Ernest defensively. 'It's going away.'

At that moment, Mr Roberts reappeared.

'The power will be back at any minute,' he ¿nnounced. 'A swan has flown into the cable, they say.'

Amy nudged me with such vigour that my side was quite sore.

'Thank you, Mr Roberts,' said the vicar. 'Let us sing a hymn together while we wait.'

After some whispering with Mr Annett, the vicar proclaimed:

'Pleasant are thy courts above'

and we all dutifully arose in the twilit church and raised our voices. As we reached the last line, the lights came on again, and we sang 'Amen' with undue fervour.

We resumed our seats expectantly and Basil Bradley, looking slightly careworn, appeared at the chancel steps.

'I think we had better begin again from the beginning, ladies and gentlemen. We are so very sorry for this breakdown. Please bear with us, and let us hope that all is now plain sailing.'

There were sympathetic murmurs from the congregation, the lights went out and the blue spot-light lit up the altar once more. There was a preliminary crackle and then Basil Bradley's voice as before.

'Long, long ago, so learned men tell us, the Romans may have passed this way.'

We settled back, like children hungry for a story, and gave ourselves up to enjoyment.

It took a little over an hour for the tale to unfold, and so well had Basil Bradley told it and so beautiful had the lighting been, that we emerged from the experience filled with unbounded admiration tinged with awe.

Even Amy was impressed.

'Remarkably

good,' she said as we walked home. 'Really

outstandingly

good! It ought to bring hundreds of visitors.'

'Let's hope it does,' I replied. 'Two thousand pounds takes some finding.'

'I wonder if the national press will write it up,' mused Amy. 'It deserves it. You'll get people from all over the place if it's widely advertised.'

'We've done our best,' I assured her. 'It's been in all the local papers, I know.'

'I think I shall send a letter to

The Times',

said Amy, climbing elegantly into her car. 'We want to cast the net

really wide.'

She drove off and I returned to the school house. Distant voices in the lane and the sound of cars starting on their homeward journeys formed the epilogue to Basil Bradley's moving production.

A star, bright as a jewel, hung beside St Patrick's spire. It looked hopeful, I thought, as I prepared for bed. If the rest of the Fairacre contributions matched this evening's in splendour, our Festival must surely succeed, and more important still, Queen Anne's chalice would remain among those who loved it so well.

Chapter 7

N

EXT

morning I began to realise just how far-flung the news of our Fairacre Festival had been.

There was a hearty banging on the classroom door during our history lesson and in walked a thickset man wearing a crewcut and a broad smile. The likeness to our Mr Lamb at the Post Office was unmistakable.

'Miss Read?' he began.

'George Lamb,' I said. 'How nice of you to look in!'

'Well, you see, I was raised in this place and I felt I just had to take another peek at this old schoolroom. Don't appear to have changed much since my time. Bit cleaner, perhaps.'

'You'd better repeat that to Mrs Pringle,' I told him. 'It'll make her day.'

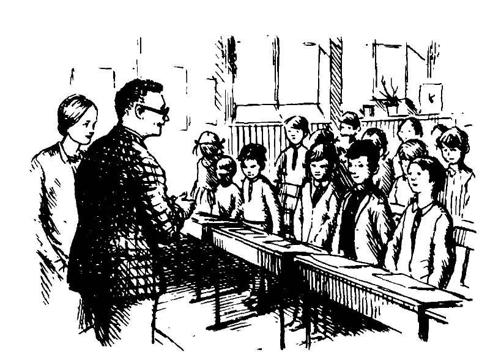

I turned to the class.

'Stand up and say "Good-morning" to Mr Lamb, who was once a pupil here.'

There were welcoming cries and smiles, all the warmer because any interruption to lessons is a pleasurable one.

'That's a Coggs,' exclaimed our visitor, pointing delightedly at Joseph in the front row.

'Quite right,' I said. 'He's Arthur Coggs' son.'

'Oh, I know

Arthur,'

replied George Lamb with some emphasis. I had no doubt that he knew a great deal about his old schoolmate's fondness for liquor and the resultant shindies in our village.

I settled the children to some work and accompanied our guest on a tour of the room.

'Not the same piano! Sakes alive, that must be going on for a century.'

'Eighty, anyway,' I agreed fingering the walnut fretwork front, and the ivory keys, yellow with age.

'And still the same gaps in the partition,' he went on, bending down to squint through a crack into the infants' room. 'The things we poked through there you'd just never credit, Miss Read.'

'Mr Willet's told me,' I assured him. 'Stinging nettles, knitting needles, dozens of notes—yes, I can well imagine. It happens still, you know. Children don't change much.'

He ambled appreciatively round the room, touching the walls, peering from the windows, and ruffling the children's hair as he passed.

'I hear Miss Clare's still at Beech Green. I'm paying her a visit before I fly home.'

'She'll be so pleased,' I said truthfully.

'I owe a lot to her,' he said, suddenly grave. 'Taught us all proper manners and to think for others. She used to say grace before we went home at night. It went: "Bless us this night and make us ever mindful of the wants of others." I always liked that. "Mindful of the wants of others." Good words those.'

He gazed through the window as he spoke, his eyes fixed upon the men working upon St Patrick's belfry.

'They're getting on very well. They've almost finished,' I said, intending to release the tension a little. George Lamb shook himself into the present again.

'Ah! Looks pretty tidy now. You been to the show there yet?'

I said that I had.

'I'm taking some of the chaps who flew over with me tomorrow night. All helps the funds. I owe a lot to Fairacre, and it'll give the fellows no end of a kick to see a building that's over eight hundred years old, and to hear Jean Cole too.'

He glanced at the square gold watch upon his wrist and grimaced.

'Best get back to the Post Office for my lunch, or I'll catch it,' he said. 'Goodbye, Miss Read. Goodbye children. Hope you'll look back on your days at Fairacre School with as much pleasure as I do.'

I accompanied him to the gate. Above the elm trees the rooks were circling high.

'Sign of rain, eh?' he said. '"Winding up the water," we used to say as kids. You know one thing, Miss Read? Everything seems a lot smaller in Fairacre than I remember it except St Patrick's spire and them old elm trees! Maybe they've both been growing since I left here.'

Chuckling at his own fancies, he made his way back to the village.

On Tuesday evening came the eagerly awaited visit of Jean Cole.

Halfway through the recorded story of Fairacre there was an interval. A spotlight lit the chancel arch and the vicar led in the majestic figure of Major Gunning's cousin. She was resplendent in a long glittering black gown, and her appearance alone was enough to awe her country admirers, but when that glorious voice wrapped us in its warmth and beauty we were touched as never before.

She sang the aria from Handel's

Judas Maccabaeus,

to Mr Annett's accompaniment on the organ. It was a felicitous choice for it celebrated the restoration of the Sanctuary of Jerusalem. We sat in wonderment as the lovely voice soared and fell, and when finally she bowed and left us, we still sat silent and spellbound, whilst through my mind ran Shelley's lines:

'Music, when soft voices die,

Vibrates in the memory'—

I heard later that George Lamb was as good as his word, and that eight of his business friends had been among that evening's congregation.

After the performance was over, it appears, the vicar found them looking round the church in the company of the honorary architect, Mr Graham. He was busy pointing out the particular beauties of the building, and had a fascinated audience. The vicar joined the party and was moved to see the awed admiration with which the strangers viewed the ancient building.

'Back home,' said one, 'we reckon two hundred years as mighty old. It takes your breath away to touch a wall or a doorway this ancient.'

They wandered from vestry to belfry, from altar to side-chapel, and finally emerged from the west door and accepted the vicar's invitation to coffee at the vicarage.

'I can offer you Drambuie with it,' said the vicar with pleasure, as he handed round the steaming cups, 'or a liqueur called aurum, distilled from oranges, and brought from Italy as a present by some friends in the village.'

'Not for me,' said Jock Graham austerely, 'but I'll no refuse a good Scots liqueur like Drambuie.'

He was in a remarkably mellow mood. To have such an attentive audience was a joy to him. The villagers of Fairacre took their church very much for granted, but these strangers were perceptive and appreciative. Jock Graham's tongue wagged all the faster, as the Drambuie diminished sip by sip, and he extolled the unique attributes of the building he loved so well.

It was almost half past eleven when at last the party broke up.

'I'd no idea it was so late,' said the vicar. 'Have you far to go?'

'We're booked in at Caxley,' said one. 'Two of us have business there tomorrow. The others are off to London on the early train, rustling up some more customers we hope.'

Farewells were made, and the vicar and Mrs Partridge turned back into the hall.

'What very nice fellows!' exclaimed Mr Partridge. 'George Lamb seems to have found some good companions.'

'And a wife who's interested in cooking,' added Mrs Partridge. 'He's going to ask her to send me a recipe for almond cookies.'

'Cookies?' repeated the vicar, his brow furrowed with perplexity.

'Cookies!'

said his wife firmly. 'Biscuits to us. Really, Gerald, at times you are hopelessly insular.'

'I suppose so,' agreed the vicar rather sadly. Then his face brightened.

'But we've broadened our horizons tonight, my dear, haven't we? With our American friends, and prima donnas!'

Amicably, they mounted the stairs to bed.

The day came when Fairacre School presented its contribution to the Festival. We had decided to give two performances, one in the afternoon when mothers with young children could come, and one in the evening when fathers could attend.

We chose Wednesday for the simple reason that it is early closing day in Caxley and that the people of Fairacre would not be tempted to go there to spend their money. Thursday is market day, and three buses run from our village into Caxley on that busy day. We could not hope to compete with Caxley's magnetic pull on a Thursday. Besides, as Mrs Bonny pointed out reasonably, they would have more money to put in the silver collection

before

market day.

Excitement had mounted steadily during the Festival week, and by the time Wednesday came it was at feverpitch. The costumes and simple properties had been stacked on desks at the side of my room and Mrs Bonny's, for want of any other place to put them, and mighty little work had been done by the children with such attractions lying nearby. Pens in hand, arithmetic exercises neglected before them, the children's bemused gaze turned constantly to the glamorous heaps of clothes. Here was a glimpse of another world. Our country children rarely go to the theatre. An annual visit to the pantomime is about all that comes their way. Here, close at hand, were all the trappings of magic, the means of slipping from the everyday world of school to one of enchanting fantasy. It was little wonder that I had very few sums to mark each day. But a wise teacher knows when she is beaten, and I forbore to scold.