(9/20) Tyler's Row (10 page)

Read (9/20) Tyler's Row Online

Authors: Miss Read

Tags: #Fiction, #England, #Country Life - England, #Cottages - England, #Cottages

'Now leave your desks tidy,' I exhorted my flock at the end of their school day. 'Your parents may want to look at your books, and they don't want to see half-sucked sweets and lumps of putty, any more than I do.'

There was a feverish scrabbling among their possessions, and the waste-paper basket overflowed in record time. I saw them out thankfully, did my own tidying, and went across to the school house to have an hour or two's breather before facing the rigours of a social evening.

At seven-fifteen, clad in my best black frock which Fairacre knows only too well, I went back to the school-room bearing a handsome bowl of King Alfred daffodils which I was lending for the occasion.

It looked rather splendid, I thought, on top of the ancient piano. Mrs Johnson, rushing in two minutes' later, stopped short in her tracks and threw up her hands.

'Well, that thing can't stay there,' she said, advancing upon my beauties. 'The window sill, I think.'

'It's not wide enough,' I said mildly. 'Anyway, what's wrong with the top of the piano? They show up rather well there.'

'The piano,' explained Mrs Johnson, with ill-concealed impatience, 'is to be

in use.

It will have to be

open

for the duets and the accompaniments.'

'You'll be lucky,' I told her. 'It's never been opened since the skylight dripped on it and the wood swelled.'

Mrs Johnson breathed heavily and turned a little pink, but banged the bowl back on the piano top, and turned away.

Parents began to arrive thick and fast, and I kept a 'sharp look-out for my old friend Amy, whilst welcoming them at the door. Amy is not a parent at all, but she was at college with me and sometimes does a little 'supply' teaching to keep her hand in. At this time she was helping at the same Caxley school at which our speaker, Mrs Jollifant, was a member of staff. Consequently, Amy had double entry, as it were, into tonight's festivities.

I saw her soon enough, in an exquisitely cut burgundy-red wool frock. One large cabuchon garnet swung on a long gold chain about her neck, and her dark red shoes I mentally priced at twelve pounds. We kissed each other with real affection. Amy, though she tries to boss me, is very dear to me, and the memory of horrors shared at college binds us very close.

'Put me somewhere at the back,' she said, with unusual modesty.

'Not in that frock,' I said. 'You'll sit in the front and delight all eyes.'

The vicar settled matters by taking her arm and leading her to a seat next to his own, and very soon afterwards he opened the proceedings with an admirably clear explanation of the reasons for our being gathered together.

'We are particularly fortunate in having Mrs Jollifant for our speaker,' he said. 'She will be with us in a few minutes, but has to attend another meeting in Caxley first. Meanwhile, we will have a short session of community singing, if someone will give out the booklets.'

I rose to oblige. These dog-eared pamphlets date back to the days of war—the last war, I hasten to add—though you might not think so on reading the contents.

'Pack Up Your Troubles In Your Old Kit-bag' and 'Tipperary' are there, relics of World War One, and 'Goodbye, Dolly, I Must Leave You' carries us right back to the Boer War seventy-odd years ago. However, 'Roll Out The Barrel' redresses the balance a little, and 'She'll Be Coming Round the Mountain' seems positively up-to-date.

At any rate, all Fairacre knows them well, and we sang lustily, to Mrs Moffat's somewhat erratic accompaniment on the piano. The daffodils nodded vigorously on the tightly-closed lid, much to my satisfaction.

When we were exhausted, the vicar introduced Mr Johnson as our next contributor to the general gaiety.

'He is going to sing to us,' said the vicar, with a hint of resignation in his tone which I thought misplaced.

Mr Johnson, clutching a sheet of music, made signals to Mrs Moffat. What would it be? I half-hoped for a spirited rendering of 'The Red Flag'. His three ebullient children had taught the rest of the school a lively ditty in the playground which had become very popular.

It went:

Let him go or let him tarry,

Let him sink or let him swim,

He doesn't care for me

And I don't care for him:

For I'm the worker, he's the boss

And the boss's day is done,

But the worker's day is coming

Like the rising of the sun.

But Mr Johnson did no more than sing 'Bless This House' in a pleasant baritone, and with the mildest of expression. I felt cheated, but the general applause was warm.

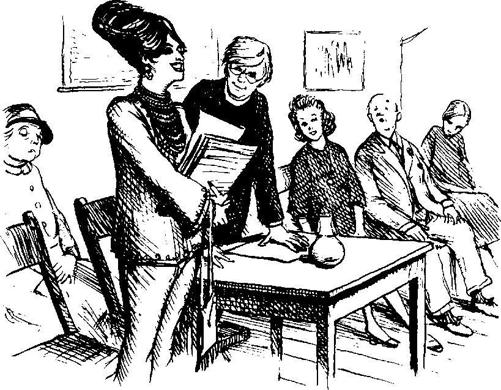

Mrs Jollifant arrived at this juncture, a dazzling figure in a trouser-suit of shimmering metallic thread. There were some looks of disapproval from the older ladies in the audience, but the young mothers gazed in open admiration.

Her hair was piled high in a tea-cosy style, and was of that intense uniform blackness which only a hairdresser can achieve. She carried a beaded and fringed handbag and an ominously large bundle of notes.

After polite clapping, Mrs Jollifant began her little talk. The time was eight o'clock.

At twenty past, she had covered what she described as 'The preliminary steps to forming a Parent-Teacher Associaton.' By eight-thirty we had heard of the Necessity For Cooperation, Keeping Abreast of Modern Methods, and the Need for Constant Discussion Between Parent and Teacher.

The two tea-ladies here tip-toed out across the creaking floorboards to turndown the boiler which was bubbling in readiness for the tea and coffee. I noticed that they did not return.

By ten to nine, a certain amount of fidgeting began, and one or two young mothers whispered agitatedly to each other. Mrs Jollifant's address flowed on remorselessly. Amy, sitting between the vicar and me, sighed noisily, and crossed one elegant leg over the other. I admired the beautiful shoes without envy, and hoped that the rumbling of my stomach was not heard by anyone but myself. A cup of coffee would have been welcome half-an-hour ago. Now it was needed as a desperate restorative.

St Patrick's church clock struck nine, but this did not perturb our speaker. We had now reached The Benefits To Our Children stage, with a lot of stuff about Flowering Minds, Spiritual Needs and the Sharing of Love and Experience. Every profession, I thought wearily, has its own appalling jargon, but surely Education takes the biscuit.

At nine-fifteen Mrs Mawne rose, with considerable clattering, and said she really must go, as it was getting

so late.

Mrs Mawne does not lack moral courage, and though the general feeling was, no doubt, of disapproval at such behaviour, there was a certain amount of envy as we watched her depart into the night.

The two tea-ladies, emboldened by Mrs Mawne's gesture, now put their heads round the door and asked if they should make the tea.

Mrs Jollifant, not a whit abashed, said she would be exactly five minutes, was exactly fifteen, and at length sat down to thunderous applause activated by relief rather than rapture.

Stiffly, with creaking joints, rumbling stomachs and slight headaches, we made an ugly rush upon the tea, coffee and sandwiches, before embarking on a shortened second half of our social evening.

Later, by my fireside, Amy and I caught up with our own affairs. James, her husband, now had to go to London regularly twice a week, and stay overnight, she told me.

'An awful bore for him,' said Amy, fingering her gold chain. 'He brought me back this garnet last week.'

Amy has a collection of beautiful jewellery which James brings home after his business trips. Sometimes I wonder if Amy has suspicions, but she is a loyal wife, and says nothing.

'It's simply lovely,' I said honestly.

'You should wear red,' said Amy, studying me, and looking as though she found the result slightly repellent. 'I've told you before not to wear black. It positively

kills

you.'

'But I've got it! I must wear it. It's hardly been worn at all.'

'Now, that's a flat lie. To my knowledge you've had it four years. You wore it first to my cocktail party.'

'I may have had it four years—that's nothing in Fairacre. I don't get much opportunity to wear this sort of frock. It'll do for another four easily.'

'Put it in the next jumble sale, and buy yourself a red one. Give Fairacre a treat. Or what about a sparkling trouser-suit like Mrs J's?'

'No thanks.'

Amy lit a cigarette.

'Detestable woman! I try and avoid her at school. She wears emeralds with sapphires.'

'Bully for her,' I said. 'I'd like the chance to wear either of 'em. My Aunt Clara's seed pearls are about the nearest I get to the real thing.'

Amy blew three perfect smoke rings in a row, one of the ex-curricular accomplishments I watched her learn at college.

'She's such a phoney,' said Amy. 'All that terrible stuff we heard tonight! If you could only see her three children!'

'No Flowering Minds? No Sharing of Love and Experience?'

'Plenty of that all right,' said Amy darkly. 'The two youngest are at school. The eldest, an unattractive amalgam of hair and spots, is at one of the danker universities in the north. He brought his girl-friend home for the entire vacation. Heavily pregnant too.'

'Is he going to marry her?'

'Well, it's not his baby, so he says, so probably not. Could you squeeze another cup of coffee out of that pot?'

I poured thoughtfully.

'What about the other two?'

'Both on probation. One steals, the other fights, and they both lie. I'd give them two years before the mast rather than probation, but of course it does mean Mrs Jollifant gets seen too by the probation officer when he visits.'

'You'd think she'd keep quiet about children,' I said, 'having such horrible children of her own.'

'The Mrs Jollifants of this world,' Amy told me pontifically, 'do not recognise horrible children—least of all their own. By the time your Parent-Teacher Association has brain-washed you, with half-a-dozen speakers like Mrs J, you'll think they're all perfect angels too.'

'That'll be the day!' I told her, reaching for the coffee-pot.

9. Callers

MAY, that loveliest of months, surpassed itself as the Hales settled into their new home. Shrubs, which had stood half-hidden by dead grass and weeds when Peter and Diana had first visited Tyler's Row, now flowered abundantly. Lilac bushes, pink, white and deep purple, tossed their scent into the air, and a fine cherry tree dangled its white blossom nearby. Unsuspected bulbs had pushed up bravely, and delighted them with late flowering narcissi and tulips. Those perennials which had escaped the notice of Mr Roberts' cows, flourished in the fine dark soil, and Diana already made plans for new beds in the autumn.

She was so busy that she had no time to miss the whirl of Caxley's social life. It was a relief, she found, to be free of coffee mornings, bazaars, cheese and wine parties, and all the other fund-raising affairs which she had felt obliged to attend. The invitations still came, but she was able to answer truthfully that she had too much to see to at the moment.

The workmen were still with them, and at times Peter wondered if they would ever go.

'I confidently expect to wrap up Christmas parcels for them,' he commented gloomily, watching their van depart one teatime. 'I shall give Bert a bottle of shampoo, and Frank a belt to keep up those filthy jeans. Binder twine doesn't appear to do the job.'

Bert and Frank were two cheerful youths, self-styled 'subcontractors', who were engaged in the last stages of the outdoor painting. They were accompanied everywhere by a transistor radio which blared out a stream of pop music to the unspoken despair of Diana, and the very outspoken fury—when he was there to hear it—of Peter. As they plied their brushes, squatting on their haunches or balanced on ladders, they shouted above the din to each other. Diana heard their exchanges and found them incomprehensible.

''E fouled 'im right 'nuff. Ref be blind 'arf the time.'

'Ar! Wants to drop ol' Betts. Never make the fourth round with 'im in goal. See 'im Sat'day?'

Football appeared to be the only topic of conversation, and this was punctuated with occasional bursts of discordant song with transistor accompaniment.

At eleven each morning, Diana made coffee for them. She carried it into the sunshine, and they knocked off with alacrity and sat on the garden seat. Sometimes she sat with them and they told her about their families. To her eyes they appeared only children themselves, but Bert had two boys of his own, and Frank three girls.

After ten minutes, Diana would hurry back to her work, but the two young men remained sitting and smoking until half-past eleven or twenty to twelve.

'Ah well,' one would say, rising reluctantly, 'best get back, I's pose.

'Ar! Get the ol'job done,' the other would agree, and they would amble back to their paint brushes, much refreshed.

And their wives, thought Diana, are scrubbing, and washing, and ironing, and cooking, and shopping, and dressing and undressing young children, and generally running round in circles. And when their husbands get home, no doubt the wives will think indulgently: 'Poor things, they've been working hard all day! Must give them a good meal, and let them have a nice rest while I wash up and put the children to bed!'