A Blaze of Glory (30 page)

Grant focused now on the uniforms emerging onto the deck of a larger supply vessel, men gathering along the rail at the closest point Grant’s boat could reach. One man stood out, the wide hat, thick bush of mustache, the lean handsomeness of Lew Wallace. Grant felt relief at that, too, pleased that Wallace would receive him without Grant having to disembark.

The sailors around him were in action now, ropes tossed out, men on both boats pulling together, the

Tigress

sliding in closer to the larger boat. They were only a few feet apart now, and Wallace stood tall, straight, saluted him, said, “General, welcome to Crump’s Landing. We seem to have something of a conflict upriver.”

Grant waited for the boats to draw tight, nearly touching, their hulls kept apart by thick pillows of canvas. He leaned closer, felt a sudden need for discretion, too many ears, too many crewmen and aides he didn’t know. Wallace responded, leaned out across the railing, close to Grant’s face, and Grant said, “What kind of conflict, General?”

He hoped for more than a casual response, but Wallace shrugged, surprised him.

“Not really sure, sir. Broke out about dawn, been going on since at a steady rate. Seems to be something of a general engagement, if I may offer the observation. With all respects, sir, I must state that I certainly share your confidence in the division commanders you have placed there. Any problem they encounter will soon be eliminated.”

Grant turned, looked upriver.

“Sounds to me like the only damn thing being

eliminated

is artillery shells.”

Wallace said, “Sir, I have put my men into readiness. My division is prepared to march toward those guns on your instruction.”

“Good. Keep them ready. For now, you will hold your division here, and await my orders. I must learn just what we’re facing. I will send for you if needed.”

“Of course, sir. We will march on your order.”

PITTSBURG LANDING APRIL 6, 1862, 11:00 A.M.

There was space along the shoreline, a short distance from the mass of boats already moored there. Some of those were in motion, pulling away, making a wide turn in the river, starting their journey back toward Savannah. He ignored that at first, too many boats in this crowded waterway to warrant any serious attention. But there was a difference now, something catching not his eye but his ear. He looked out toward a larger vessel, slipping closer beside the

Tigress

as it moved away, and on the deck he saw them, uneven rows of men, some wrapped in white, some with filthy uniforms, made more filthy by their own blood. He knew what this meant, the decks crowded by far too many men for some simple skirmish. The sounds from the boat came to him with perfect clarity, a sound he had heard before, in every place there had been a fight. Among so many wounded, many of the men were screaming.

On the vessel, there were others in motion, doctors, the unmistakable aprons of men who were doing the dirtiest work of all, the men who sawed the limbs and plugged the bloody holes. One man looked out toward Grant, a distant stare, no recognition of Grant, just staring away, as though escaping the moment, a brief rest. But he returned to his duty, knelt low, doing something to one of the soldiers Grant couldn’t see. There was nothing for Grant to do, no calling out, no questions. Along the shore, more boats were loading the wounded, men hauled up gangways on stretchers, others limping on their own, makeshift crutches, some helped by other soldiers. From every deck on every boat came the sounds, the horror of their suffering. Grant scanned the boats, the same scene across every deck, felt a stirring inside, knew there would be more belowdecks, out of sight, and in time, many of those men would be dead, stacked somewhere else, out of the way, to make more room for the steady flow of men who still might have some chance to survive.

“What in God’s name is happening? What have they done?”

The words came from Rawlins, his aide close beside him now, no more skulking behind, no need for discretion. Rawlins was answered by a new burst of the sounds from the artillery, and Grant had no trouble now guessing the distance, two miles, maybe three, the thunder coming in a wide line inland from the landing, the battle obviously spread across the camps of most of his army.

Grant looked up at the bridge of the boat, thought, I must get ashore … but the captain was already anticipating the urgency, the boat shifting its way through the gap, aided by men on other boats, ropes tossed quickly, men straining to slide the boat into place, anywhere a plank could be laid. Grant felt the rumbling beneath his feet suddenly grow still, the belching smokestacks silent. The roar of the fight was magnified now, unmasked by the quiet of the boat’s engines. He stared at the shore, ravenously impatient, turned awkwardly on the crutches, pushed past Rawlins, hopped down the short stairway to the lower deck. He expected to see the gangway already in place, the flat, wide planking, but onshore, men were tussling, one man down, fists flailing, another grabbing the plank, tossing it into the water. More men were in the water now, some swimming through the short gap to the riverboat, grabbing for the sides, one man shouting obscenities, another, his words reaching Grant with a shrill high-pitched voice: “Let us on! We have to get away! We are all dead!”

More sailors rushed along the shoreline, fighting through crowds of soldiers, officers understanding just who had arrived. The tussles and fistfights were more one-sided now, army and navy men, guards and provosts, shoving and punching their way through men who were obviously exhausted, whose energy had been spent trying to reach the river. The gangway was pulled from the river, guards holding away the men who still made the effort to reach it, and quickly, the planking was laid in place against the opening in the railing of the

Tigress

. Onshore, men on horseback moved through what Grant could see was a growing mass of soldiers, the officers raising their swords, drawing pistols. Gradually the area close to the gangway was cleared, and Grant saw his horse, led forward from the stern of the ship. Rawlins shouted through the din, “Sir! You may ride now! The ship is secured!”

Grant stared at the raw chaos along the shore, thought, secured from what? These are our men … my men.

He took the reins from Rawlins, another of the aides holding the crutches, the men boosting Grant into the saddle. The horse seemed to surge toward the plank, as anxious as any land-loving soldier to leave the boat. Grant fought with the reins, eased the horse down slowly, his staff following behind on their own mounts. He moved away from the river, expected some kind of greeting, some official welcome of his presence, saw officers still grappling with the surge of men who seemed to pour down from the higher ground in a steady wave. He felt a stinging helplessness, a brief moment when he had no idea what to do, forced the thought out loud.

“I am General Grant! Who is in charge here?”

The words were consumed by the noisy panic around him, more men pushing past, leaping into the water, some trying to climb aboard the other boats, the sailors hauling the planking upward to prevent the men from making the climb to the decks. Behind him the sailors of the

Tigress

did the same, the gangway pulled away from the bank, a chorus of shouts and curses directed their way. Grant nudged the horse forward, could see farther down the shoreline, the high embankment that bordered the river pockmarked by caves and hollows, places the river had gouged from the rock and dirt. In every hole, men had gathered, packed tightly, dirty faces and ragged blue uniforms, more men trying to shove their way in. Where there was space, the men disappeared into the mob, but others were tossed out, fists flying, some knives drawn, furious men striking out. Grant absorbed it all with a sickening horror, realized that the men were mostly weaponless, no muskets at all. Above him, more of them added to the growing crowd, some in the roadway cut through the bluff, others just tumbling down over the edge, all of them heading to the river.

“We’re done for! They’s right behind us!”

Grant watched the man slide past him, stumbling about in a daze, staring at the river, another man beside him, looking up at Grant, shouting, “We gotta get away! Get to the boats! They whipped us!”

His staff had surrounded him, obvious protection, Rawlins close to him.

“Sir! We have to get up the hill, away from the river. It is not safe here!”

Grant looked at him, saw Rawlins’s usual concern, everything in its place, every bow tied precisely. But there was nothing precise here. Grant shouted again, “I must find what is happening! I will ride forward, but keep some of the aides here, have them locate someone in authority! I must know what is happening!”

A horseman came down the steep passageway through the rocky embankment, pushed his way through more of the fugitives, aimed his way toward Grant. Grant recognized him, an aide to General Hurlbut, and the man drew up close, shouted, “Sir! It is good you are here! We must move inland with all haste!”

Grant saw a hint of panic in the man, said, “What is happening here, Major?”

The man seemed to ignore the flood that continued to pour down onto the riverbank, as though this scene had been playing out for a while.

“Sir, if you please … we must move inland! The enemy has engaged us across our entire front! There is much confusion.”

Grant felt a spring uncoil in his brain, fury at the man’s obviousness.

“Why is there

confusion

, Major? Who commands these soldiers? By damned, what is happening?”

The man offered no response, his attention caught by a horseman close by, Grant seeing a young lieutenant waving his sword, striking hard at the shoulder of a man who ran past. Downriver, the scene was repeated, officers making some attempt to control the mob, hard shouts for the men to return to duty, to make a stand. But the panic in the men swept away the commands, more calls from the men who came down the hill, a chorus of terror and despair, that all was lost, every man doomed. Grant spurred the horse, had no more need of the major, could see too clearly that his army had been struck by a blow that had ripped away their spirit, their hearts, their ability to fight. He pushed the horse up the hill, past the wagons, saw the two small buildings, run-down cabins, wounded men lying there as well, more coming, too few doctors to help them.

Grant rode farther along the road, saw horses standing about, no riders, wagons untended, teams of artillery horses jogging past, linked together, trailing leather straps, no sign of their limbers or the artillerymen who had manned the guns. Through it all, the sounds of the fight continued to roar across the ground in front of him, distant yet close, unceasing, a fight that seemed to grow wider and louder, as though swallowing his army completely, a fight he had never expected.

JOHNSTON

NEAR SHILOH CHURCH APRIL 6, 1862, 10:00 A.M.

F

rom first light he had stayed close to the front lines, brief and frantic meetings with his commanders. The fight had grown chaotic almost immediately, the plunging strike into Federal forces destroying most of the organization of the neat lines of battle. The confusion had more to do with the lay of the land than the defense put up by the Yankees, the treacherous ravines and thickets preventing any kind of order. In every part of the field, regiments were splitting apart, their individual companies losing touch with one another, men fighting in small pockets wherever their enemy happened to be.

It was obvious to Johnston, as it was to Hardee and Bragg and anyone else up front, that the attack thus far had been an astounding success. Johnston had seen for himself what the cavalry had reported for more than a week, that the Federals had made no preparations to receive an assault. There were no trench works, no abatis, the Federal troops thrown into line often in complete disarray. Those fights had been the easiest, the Confederate troops driving their enemy back in a complete panic, Federal officers as well as their men scampering away with the first few volleys. But others had held their ground, and Johnston saw that as well, vicious firefights, often yards apart, men shooting through thickets where the enemy was only a flicker of movement, artillerymen aiming cannon toward clouds of smoke, the only hint they had where the enemy might be. On both sides, the artillery seemed to be accomplishing the most effective work, and the big guns were soon targeting the enemy’s artillery as much as enemy troops. All across the fields, batteries were dueling batteries with horrifying results for the men and their horses. With the help of the infantry, cannons were captured, lost, recaptured, and often the men who had manned the guns were long gone, shot down or swept away in a panic, while the fate of their guns had become one part of an enormous bloody contest.

Johnston had spent his first couple of hours close to Hardee’s men, had heard for himself the great push that had driven back Sherman, and then Prentiss, the enemy prisoners never hesitant to reveal who they served. The Federal troops had made efforts in every part of the field to find a new position of strength, backing to another ridge, another thicket, where their fight could begin again. It was completely expected that the men in blue would not do what so many had predicted, those mindless claims of their utter cowardice, that no Union man could make a stand against the raw dedication of the man in gray. Johnston knew better, saw it now, in every ravine, on every hill. While many of the bluecoated men had chosen escape, a great many more had stood up to fight, and many of those had fallen on the ground where they had made a stand, dead and wounded spread across every piece of ground where Johnston’s men had made their push. But there was no mistaking that, so far, most of the dead were wearing blue, and some of those had not been in the fight at all. The Confederates had shoved hard right through the camps of the Federals anchored farther to the west, Sherman’s Division in particular, and so, many of those men had not had time to gather into effective formations to receive the assault. Some had been in the midst of breakfast, some still in their tents, the sick and injured still in their bedrolls. Some made the effort, but the Confederates had every advantage, swept through and past the unprepared enemy with brutal efficiency. The message was clear now to Johnston, and to anyone else who saw the standing tents. This attack, the tactics and strategy of the great surprise, had worked.

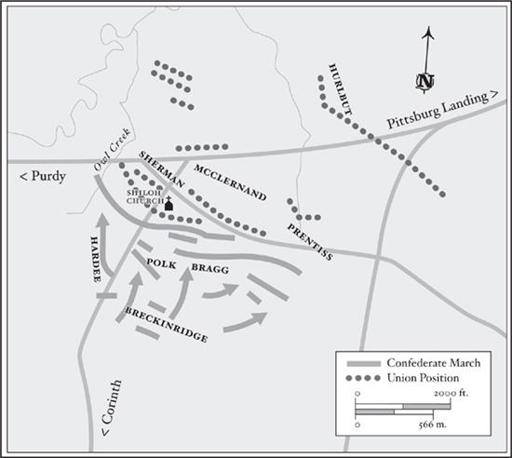

THE CONFEDERATE ATTACK, AS LINES SPREAD OUT

T

he fighting closest to him was scattered, sudden bursts of musket fire through smoky brush, men on both sides stumbling into their enemy, blinded by smoke and thickets of briars and vines. Johnston could hear the whistle of the musket balls, looked back toward the trailing line of horsemen, most of his staff following, some of the men reacting to the sound of the firing with lowered heads.

“Careful, gentlemen. I want no casualties here. If you see the enemy, move quickly away!”

He followed his own order, ducked low beneath a broken tree limb, could smell the spent powder in the air around him, sulfur burning his lungs. He knew the staff would stay close behind him, and he spurred the horse hard, jerked the reins, saw a massive flash of fire in front, artillery erupting very close. He had no idea who they were, pulled away, putting distance between his staff and the guns, thought, ours, certainly. Has to be. We have not yet ridden anywhere the enemy is in force. But still …

He led them up a knoll, saw officers, a cluster of horses and flags, felt a glimmer of relief, grateful for the calming presence of Leonidas Polk. Polk saw him coming, stepped the horse out toward him, a smiling salute.

“A glorious Sabbath, General! May I say, this army is performing in a most excellent manner. Most excellent, indeed.”

Polk’s smile was usually contagious, but Johnston felt a stab of something very uncomfortable.

“It is the Sabbath?”

“Yes, of course. Surely you knew …” Polk stopped, seemed to realize that Johnston had no idea. “It is all right, Sidney. God does not fault us for victory. And from what we have accomplished, a victory seems assured.”

It was a strangely optimistic statement, and Johnston’s discomfort turned to alarm. Polk seemed to sense where his words had taken his friend, the smile fading.

“I’m sorry, Sidney. But there is no harm in striking your enemy when the cause is just in the eyes of God.”

Johnston didn’t respond, looked past Polk’s staff to a rising cloud of smoke, more hard thumps coming from a nearby hill, batteries firing eastward, Polk’s batteries. The muskets began again, more distant, and in the low ground to one side, the rebel yell exploded in a chorus of terrifying passion, a surge of men Johnston couldn’t see, pushing their way up the hill, toward an enemy somewhere beyond the next rise. The fight consumed everything around him, smoke and noise, deafening and magnificent, and he tried to feel Polk’s optimism, the pure joy of a victory, his army seeking their triumph so close to him. But there was something still rattling hard through Johnston’s brain, a scolding, the lesson from his grandfather, so long ago, a young boy who sat spellbound while the old man preached to him of hell and damnation and the wrath of the Almighty, all those lessons that terrified the young. The old man had died nearly forty years ago, but some of those fearful lessons had stayed with Johnston, and he thought of it now, felt a wave of new sadness. This is Sunday. We should not be making the fight … this day. Polk should understand, he thought. It was all of the delays … the interminable rains. I did not consider the calendar, the days of the week. We could have waited one more day. He knew that wasn’t true, the voice of the general taking command of his wits. We took great risk as it was. One more day … and the enemy might be driving into

us

.

Johnston was drawn by a new round of volleys, farther out to the left, Polk’s men again, still coming forward, more of the rebel yell.

“Yes, pray for us all, Bishop. This day is not yet done, and the enemy is still very dangerous. We must not become overconfident.”

The fight close by seemed to fade, musket fire in slow pops, more yells from the men as they crested the far hill, in pursuit of a retreating enemy. Polk had his field glasses up, said aloud, “We have driven them back once more!” He turned to Johnston again. “You see? The Almighty watches us, our every move, and He strikes our enemies with the punishment they have earned. This is glorious, Sidney. Glorious!”

Johnston wanted to feel that joy, could not escape the scolding of his grandfather.

“Perhaps. But remain vigilant, remain aggressive. The wagons must maintain pace with your advance. Ammunition can become a problem, and I want these men supplied!”

Polk responded, “Of course. I shall see to it. But you had best put those wagons to a gallop! We are driving for that river, Sidney! God is providing the path!”

Johnston turned his horse, was still unnerved by his friend’s overwhelming cheer. He turned to Major Munford, closest to him, said, “We will move farther to the right. If General Bragg can be found quickly, I would speak with him. I must know if progress on his front is as it is here.”

He spurred the horse, did not look back at Polk, felt nervous, agitated, thought, it cannot be wise to assume God is standing with your men, that God wields the weapons that will drive the enemy away. We are still men. And this fight is being made by men on both sides who are dying for their honor. Which of those men has God’s greater blessing?

There was another firefight in the trees before him, a fresh line of troops moving up from the right. He saw the flag, Arkansas, men pushing through the brush with another wild cheer. They passed by him, unseeing, their focus on where the enemy might be. From far to the left, the brush erupted into a single burst of smoke, Federal troops lying in wait, the volley punching through the Arkansans, men collapsing within a few yards of where Johnston sat. He turned away from that, realized he was in a very bad place, that the woods could disguise anyone, anywhere. The staff needed no instruction, followed as he dipped down into a gulley, riding through a narrow creek bed, away from the smoke. They climbed up into clear ground again, and across the field he could see another battle line, Texans this time, another advance, at least a full regiment, their far flank disappearing into a thick stand of trees. Men saw him now, and muskets rose, the cheering directed toward him, whether they recognized him or not. What they saw was a commander, sitting tall, and now their own officers appeared, one man riding toward him at a rapid trot. Johnston knew the man, tried to recall his name, the insignia of a colonel.

“Sir! With all respects … this is not the place for you! You are exposed to the batteries of the enemy! Please, sir, withdraw. The Yankees are on that ridge … there!”

As the man uttered the words, the ridgeline in front of the colonel’s men burst into a furious cascade of firing, the sharp whistle of the shells impacting all across the field, punching great fiery gaps through the lines of men. The colonel turned, attentive to his men, a quick glance back at Johnston. “Sir! Please!”

Johnston waved the man away, the colonel needing no instructions, the man now following close behind his men, the entire line dropping away into low ground, disappearing into a billowing fog of gray smoke. More artillery came down now, a half-dozen blasts, and Johnston turned the horse again, shouted to his staff, “That was excellent advice! Let us retire beyond those trees!”

He led them again, pushed through a stand of thinly spaced hardwoods, saw more of his men coming forward, a fresh line, some of the men making way for him to pass. He searched for their flag, had to know, saw Alabama now, grim-faced men who acknowledged him with calls and shouts. Their officers rode up close, fought their way through the timber, but Johnston did not stop, had no need to halt men who were marching forward. There was nothing these men should care about a general riding where he should not be. Unless they falter, they do not need me to tell them anything.