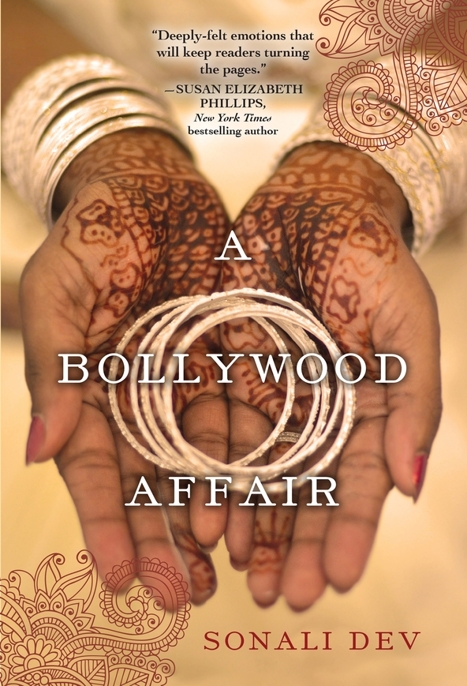

A Bollywood Affair

Read A Bollywood Affair Online

Authors: Sonali Dev

A BOLLYWOOD AFFAIR

SONALI DEV

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For Mama and Papa for living Happily Ever After

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing your first acknowledgments page has to be a lot like giving your first acceptance speech at the Oscars. You’ve practiced it in your head so very many times and yet when the moment arrives, it’s so huge, such a culmination of your dreams, of your immense good fortune, how can you ever articulate it sufficiently?

I would love to say that this book was hard labor, that my path to publication was riddled with sacrifice and tears. But I can’t. Writing Samir and Mili’s story was pure joy, and my path was riddled with the incredible generosity and support of so many people I could never name them all or ever thank them enough. But I’m going to try anyway.

First, my incredible husband for knowing exactly how to walk the tightrope between needing me and giving me space to chase my dream and for all that delicious dal, clean laundry, and faith.

My children for being as undemanding as two teenagers can ever be expected to be. If there are other children in the world who say to their mother, “You go write. We’ll make us some ramen noodles,” the future of our race is bright indeed.

My parents for never being more than a phone call away from dropping everything and rushing to my aid when I need them.

My best friend for being my sounding board, my springboard, my storyboard, not to mention my periscope into Bollywood. She believed in my writing long before anyone else did and it has been the most priceless of gifts.

My beta reader girls, Rupali, Kalpana, Gaelyn, Robin, India, and Jennifer, for the most insightful reads and for being my champions.

My friends, Advocate Pallavi Divekar, for letting me pick her legal eagle brain on Indian Marriage Laws and Village Panch Councils, and Smita Phaphat for an insider’s view into Rajasthani culture. Without them there would be no story.

My sisterhood of writers, who are without a doubt the best part of this business. The Aphrodites—Robin, Savannah, Cici, India, Clara, CJ, Sarah, Ann Marie, Denise, and Hanna—for holding my hand every single day. The Windy City RWA chapter for never letting a plea for help go unanswered. The Chicago North RWA chapter and the Golden Heart Lucky 13s for their unconditional support, and the RWA community at large for being the best example of feminine power in the entire world.

My agent, Jita Fumich, for a million questions answered, and my editor, Martin Biro, for being my Right Time and Place and for leading me through my debut with such kindness, and the entire team at Kensington for making this so very easy.

And lastly and most importantly to each and every one of you for taking the time to read my words, to you I owe my deepest thanks. Without you all these people would have supported me in vain.

PROLOGUE

A

sea of wedding altars stretched across the desert sands and disappeared into the horizon. The celebratory wail of

shehnai

flutes piped from speakers and fought the buzz of a thousand voices for attention. Hundreds of red-and-gold-draped children sat scattered like confetti around auspicious fires ready to chant their vows. The Akha Teej mass wedding ceremony was in full swing under the blistering Rajasthan sun.

sea of wedding altars stretched across the desert sands and disappeared into the horizon. The celebratory wail of

shehnai

flutes piped from speakers and fought the buzz of a thousand voices for attention. Hundreds of red-and-gold-draped children sat scattered like confetti around auspicious fires ready to chant their vows. The Akha Teej mass wedding ceremony was in full swing under the blistering Rajasthan sun.

Lata surveyed the scene from the very edge of the chaos. Her father-in-law had pulled some hefty strings to obtain this most coveted corner spot, where it should’ve been relatively quiet. Only it wasn’t, thanks to her son’s chubby-cheeked bride, who bawled so loudly Lata couldn’t decide if she wanted to slap the child’s face or pull her close. What kind of girl-child cried like that? As though she had the right to be heard?

Lata’s older son, the twelve-year-old groom, spared one disinterested glance at his bride’s ruckus before strolling off to explore the festivities. Lata’s younger son twisted restlessly by her side. Even hiding in the folds of her sari, his foreign whiteness made him stand out like a beacon against the sea of toasted brown skin and jet-black hair. Unlike his older brother, he couldn’t seem to bring himself to look away from the crying bride.

Finally, unable to contain himself any longer, he reached out and gave her fabric-draped head a reassuring pat. She whipped around, her wet baby eyes so round with hope Lata’s heart cramped in her chest. The gold-rimmed bridal veil slipped off her baby head, revealing a mass of ebony curls forced into pigtails. The boy tugged the veil back in place. But before he could finish, the girl lunged at him, grabbing her newfound ally as if he were a tree in a sandstorm, and went back to wailing with intensified fervor. Her huge kohl-lined eyes squeezed rivers down her cheeks. Her dimpled fingers dug valleys into his arm. Her soon-to-be brother-in-law winced but he didn’t pull away.

“You whoreson!” Lata’s father-in-law shouted over the bawling girl. He’d just finished up the wedding negotiations and he turned to the boy with such rage in his bushy browed gaze that Lata rushed forward to shield him. But she wasn’t quick enough. The old man drew back his arm and slapped the boy’s head so hard he stumbled forward, finding his balance only because the tiny bride gripped him with all her might.

“Get your filthy hands off her!” The boy’s grandfather yanked the girl away. “Get him out of here,” he hissed at Lata, spittle spraying from his handlebar mustache like venom. “Ten years old and already grabbing for his brother’s wife. White bastard.”

Anger ignited the gold in the boy’s eyes and swam in his unshed tears. Lata squeezed him to her belly and pressed her palm to his ear. He fisted her widow’s white in both hands, his skinny body trembling with the effort to hold in the tears. The girl’s gaze clung to them even as the old man dragged her away. Her chest continued to hiccup with sobs but she no longer screamed.

“Why does Bhai’s bride cry, Baiji?” the boy whispered against Lata’s belly, his Hindi so pure no one would know he’d spoken it for but a few years.

Lata kissed his soft golden head. It was all the answer she would give him. She could hardly tell him it was because the child had been born a girl, destined from birth to be bound and gagged, to never be free. And she seemed to have sensed it far sooner than most. Sadly, the poor fool seemed to believe that she could actually do something about it.

1

A

ll Mili had ever wanted was to be a good wife. A domestic goddess-slash-world’s-wife-number-one-type good wife. The kind of wife her husband pined for all day long. The kind of wife he rushed home to every night because she’d make them a home so very beautiful even those TV serial homes would seem like plastic replicas. A home filled with love and laughter and the aroma of perfectly spiced food, which she would serve out of spotless stainless steel vessels, dressed in simple yet elegant clothes while making funny yet smart conversation. Because when she put her mind to it she really could dress all tip-top. As for her smart opinions? Well, she did know when to express them, no matter what her grandmother said.

ll Mili had ever wanted was to be a good wife. A domestic goddess-slash-world’s-wife-number-one-type good wife. The kind of wife her husband pined for all day long. The kind of wife he rushed home to every night because she’d make them a home so very beautiful even those TV serial homes would seem like plastic replicas. A home filled with love and laughter and the aroma of perfectly spiced food, which she would serve out of spotless stainless steel vessels, dressed in simple yet elegant clothes while making funny yet smart conversation. Because when she put her mind to it she really could dress all tip-top. As for her smart opinions? Well, she did know when to express them, no matter what her grandmother said.

Professor Tiwari had even called her “uniquely insightful” in his letter of recommendation. God bless the man; he’d coaxed her to pursue higher education, and even Mahatma Gandhi himself had said an educated woman made a better wife and mother. So here she was, with the blessings of her teacher

and

Gandhiji, melting into the baking pavement outside the American Consulate in Mumbai, waiting in line to get her visa so she could get on with said higher education.

and

Gandhiji, melting into the baking pavement outside the American Consulate in Mumbai, waiting in line to get her visa so she could get on with said higher education.

Now if only her nose would stop dripping for one blessed second. It was terribly annoying, this nose-running business she was cursed with—her personal little pre-cry warning, just in case she was too stupid to know that tears were about to follow. She squeezed the tip of her nose with the scarf draped across her shoulders, completely ruining her favorite pink

salwar

suit, and stared at the two couples chattering away over her head. She absolutely would not allow herself to cry today.

salwar

suit, and stared at the two couples chattering away over her head. She absolutely would not allow herself to cry today.

So what if she was sandwiched between two models of newly wedded bliss. So what if the sun burned a hole in her head. So what if guilt stabbed at her insides like bull horns. Everything had gone off like clockwork and that had to be a sign that she was doing the right thing. Right?

She had woken up at three that morning and taken the three-thirty fast train from Borivali to Charni Road station to make it to the visa line before five. It had been a shock to find fifty-odd people already camped out on the concrete sidewalk outside the high consulate gates. But after she got here the line had grown at an alarming rate and now a few hundred people snaked into an endless queue behind her. And that’s what mattered. Her grandma did always say “look at those beneath you, not those above you.”

Mili turned from the newlywed couple in front of her to the newlywed couple behind her. The bride giggled at something her husband said and he looked like he might explode with the joy the sound brought him. Mili yanked a handkerchief out of her mirrorwork sack bag and jabbed it into her nose. Oh, there was no doubt they were newlyweds. It wasn’t just the henna on the women’s hands, or the bangles jangling on their arms from their wrists to their elbows. It was the way the wives fluttered their lashes when they looked up at their husbands and all those tentative little touches. Mili sniffed back a giant sob. The sight of the swirling henna patterns and the sunlight catching the glass bangles made such longing tear through her heart that she almost gave up on the whole nose-squeezing business and let herself bawl.

Not that all the longing in the world was ever going to give Mili those bridal henna hands or those bridal bangles. Her time for that had passed. Twenty years ago. When she was all of four years old. And she had no memory of it. None at all.

She blew into the hankie so hard both brides jumped.

“You okay?” Bride Number One asked, her sweet tone at odds with the repulsion on her face.

“You don’t look too good,” Bride Number Two added, not to be outdone.

Both husbands preened at their wives’ infinite kindliness.

“I’m fine,” Mili sniffed from behind the hankie pressed to her nose. “Must be catching a cold.”

Both couples took a quick step back. Getting sick would put quite a damper on all that shiny-fresh newly weddedness. Good. She was sick of all that talk over her head. Being just a smidge less than five feet tall did not make her invisible.

The four of them exchanged meaningful glances. The couple behind her smiled expectantly at Mili, but they didn’t come out and ask her to let them move closer to their new friends. The couple in front studied the cars whizzing by with great interest. They weren’t about to let their position in line go. The old Mili would have moved out of the way without a second thought. But the new Mili, the one who had sold her dowry jewels so she could go to America and finally make herself worth something, had to learn to hold her ground.

There’s a difference between benevolence and stupidity and even God knows it.

Her grandmother’s ever-present monotone tried to strengthen her resolve. She was done with stupidity, she really was, but she hated feeling petty and mean. She was about to give up the battle and her place in line when a man in a khaki uniform walked up to her. “What status?” he asked impatiently.

Her grandmother’s ever-present monotone tried to strengthen her resolve. She was done with stupidity, she really was, but she hated feeling petty and mean. She was about to give up the battle and her place in line when a man in a khaki uniform walked up to her. “What status?” he asked impatiently.

Mili took a step back and tried not to give him what her grandmother called her idiot-child look. Anyone in uniform terrified her.

“F-1? H-1?” He gave the paperwork she was clutching to her belly a tap with his baton, doing nothing to diffuse her fear of authority.

“Oy hoy,”

he said irritably when she didn’t respond, and switched to Hindi. “What visa status are you applying for, child?”

he said irritably when she didn’t respond, and switched to Hindi. “What visa status are you applying for, child?”

The flickering light bulb in Mili’s brain flashed on. “F-1. Student visa, please,” she said, mirroring his dialect and beaming at him, thrilled to hear the familiar accent of her home state here in Mumbai.

His face softened. “You’re from Rajasthan, I see.” He smiled back, not looking the least bit intimidating anymore, but more like one of the kindly uncles in her village. He grabbed her arm. “This way. Come along.” He dragged her to a much shorter queue that was already moving through the wrought-iron gates. And just like that, Mili found herself in the huge waiting hall inside the American consulate.

It was like stepping inside a refrigerator, pure white and clinically clean and so cold she had to rub her arms to keep gooseflesh from dancing across her skin. But the chill in the room refreshed her, made her feel all shiny and tip-top like the stylish couple making goo-goo eyes at each other on the Bollywood billboard she could see through the gleaming windows.

She patted down her hair. She had pulled it tightly into a ponytail and then braided it for good measure. Today must be an auspicious day because her infuriating, completely stubborn curls had actually decided to stay where she had put them. Demon’s hair, her grandmother called it. Her

naani

had made Mili massage her arms with sesame oil every morning after she combed Mili’s hair out for school. “Your hair will kill me,” she had loved to moan. “It’s like someone unraveled a rug and threw the tangled mass of yarn on your head just to torture me.”

naani

had made Mili massage her arms with sesame oil every morning after she combed Mili’s hair out for school. “Your hair will kill me,” she had loved to moan. “It’s like someone unraveled a rug and threw the tangled mass of yarn on your head just to torture me.”

Dear old Naani. Mili was going to miss her so much. She pressed her palms together, threw a pleading look at the ceiling, and begged for forgiveness.

I’m sorry, Naani. You know I would never do what I’m about to do if there were any other way.

I’m sorry, Naani. You know I would never do what I’m about to do if there were any other way.

“Mrs. Rathod?” The crisply dressed visa officer raised one blond eyebrow at Mili as she approached the interview window. The form she had filled out last night while hiding in her cousin’s bathroom sat on the laminated counter between them.

Mili nodded.

“It says here you are twenty-four years old?” Mili was used to that incredulous look when she told anyone her age. It was always hard convincing anyone she was a day over sixteen.

She started to nod again, but decided to speak up. “Yes. I am, sir,” she said in what Professor Tiwari called her impressive English. The ten-kilometer bike ride from her home to St. Teresa’s English High School for girls had been worth every turn of the pedal.

“It also says here you’re married.” Sympathy flashed in his blue eyes, exactly the way it flashed in Naani’s eyes when she offered sweets to their neighbor’s wheelchair-bound daughter, and Mili knew he had noticed her wedding date. Another thing Mili was used to. These urban types always, always looked at her this way when they found out how young she had been on her wedding day.

Mili touched her

mangalsutra

—the black wedding beads around her neck should’ve made the question redundant—and nodded. “Yes. Yes, I’m married.”

mangalsutra

—the black wedding beads around her neck should’ve made the question redundant—and nodded. “Yes. Yes, I’m married.”

“What is your area of study?” he asked, although that too was right there on the form.

“It’s an eight-month certificate course in applied sociology, women’s studies.”

“You have a partial scholarship and an assistantship.”

It wasn’t a question so Mili nodded again.

“Why do you want to go to America, Mrs. Rathod?”

“Because America has done very well in taking care of its women. Where else would I go to study how to better the lives of women?”

A smile twinkled in his eyes, wiping away that pitying look from before. He cleared his throat and peered at her over his glasses. “Do you plan to come back?”

She held his stare. “I’m on sabbatical from my job at the National Women’s Center in Jaipur. I’m also under bond with them. I have to return.” She swallowed. “And my husband is an officer in the Indian Air Force. He can’t leave the services for at least another fifteen years.” Her voice was calm. Thank God for practicing in front of mirrors.

The man studied her. Let him. She hadn’t told a single lie. She had nothing to fear.

He lifted a rubber stamp from the ink pad next to him. “Good luck with your education, Mrs. Rathod. Pick up your visa at window nine at four p.m.”

Slam

and

slam.

And there it was—

APPROVED

—emblazoned across her visa application in the bright vermillion of good luck.

Slam

and

slam.

And there it was—

APPROVED

—emblazoned across her visa application in the bright vermillion of good luck.

“Thank you,” she said, unable to hold back a skip as she walked away. And thank you, Squadron Leader Virat Rathod. It was the first time in Mili’s life that her husband of twenty years had helped his wife with anything.

Other books

A Victim of the Aurora by Thomas Keneally

Lone Lake Killer by Maxwell, Ian

Having My Baby by Theresa Ragan

Always And Forever by Betty Neels

The Summer Soldier by Nicholas Guild

A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories by Ray Bradbury

Racing Against Time by Marie Ferrarella

The Swarm by Orson Scott Card

Bitten: Dark Erotic Stories by Susie Bright