A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam (74 page)

Read A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam Online

Authors: Neil Sheehan

Tags: #General, #Vietnam War; 1961-1975, #History, #United States, #Vietnam War, #Military, #Biography & Autobiography, #Southeast Asia, #Asia, #United States - Officers, #Vietnam War; 1961-1975 - United States, #Vann; John Paul, #Biography, #Soldiers, #Soldiers - United States

He was correct on both counts. The human folly of crime and lawsuits is secure from economic collapse, and Jess’s occupation shielded the Allen household from the misery that pained millions of other families across the land after 1929. While Mary Jane was in grammar school and the Depression was at its worst, the family moved upward from a plain house in a suburb of Rochester to a spacious home within the city. The city government was conscientious about repairing the sidewalks and tending the big shade trees that lined Elmdorf Avenue and its neighboring streets. The Aliens’ home, like the others on the avenue, sat back behind a box hedge and a deep lawn. It was a two-story house with white siding on the ground level—the boards precisely joined and neatly painted, none of the slipshod clapboarding of the South—and green shingles on the second story. The front porch was a pleasure to sit on of a day or an evening. Mary Allen had awnings made to shelter it from sun and rain and furnished it with rockers and swings. Jess kept the lawns thriving and planted shrubbery alongside the two-car garage at the back where he parked his Chrysler and stored his gardening tools. There were four bedrooms on the second floor and an enclosed sleeping porch for summer nights. The dining room on the ground floor had bay windows, exposed oak beams, and a chandelier. Jess had the basement converted into a recreation room with a hand-crank victrola and a Ping-Pong table. Although Rochester summers are not particularly hot, the Aliens rented a cottage every July and August on one of the Finger Lakes of upstate New York, Lake Conesus, about an hour’s drive from the city. Mary Allen would go there at the end of June with the children. Jess would drive out for the weekend after Friday’s court session and then spend his summer vacation at the lake.

The Aliens were able to give each child a separate bedroom in the house on Elmdorf Avenue and still have a guest room to spare, because they had only two children. Mary Jane, the second daughter, was born

on August 11, 1927. She was bright but lacked the intellectual curiosity to be an outstanding student. Her interests were in domestic and traditionally feminine pursuits—dolls and doll houses, sewing, and playing at keeping house.

As a little girl she was a sugar-and-spice of smiles and curls and bows and fashion-plate dresses. Shirley Temple was the child movie star of the day, and the age was one in which the public admired and imitated movie stars somewhat more naively than it would later. Every little girl wanted to look like Shirley Temple. Those with mothers who had the patience to do the curling wore their hair coiled in the style that Shirley Temple made popular. Not many little girls also had enough of the Shirley Temple charm to go with the curls and be chosen by the Rochester department stores to model Shirley Temple clothes. Mary Jane Allen did. On April 23, 1934, Shirley Temple’s sixth birthday, Mary Jane and eight other mini-models displayed “exact copies of dresses that were made for Shirley herself” at McCurdy’s department store. “The juvenile fashion revue was attended by nearly 500 interested mothers and excited little boys and girls,” the

Rochester Times-Union

reported. Mary Jane had an appropriately wide-eyed look in the photograph above the story. By Shirley Temple’s seventh birthday, Mary Jane was modeling at B. Forman Company and appeared in the

Rochester Journal-American

smiling and crinkling up her nose in a way she often did if something amused her. This time she also had an oversized bow pinned into her brunette hair. And when the Westminster Presbyterian Church, where her family attended 11:00

A.M.

services and she went to Sunday school, staged a Christmas pageant, it seemed natural to choose Mary Jane Allen to play the part of Mary.

Her parents raised her to mirror their values of family and church and country, and she never questioned anything. Her Grandmother Allen had a particular effect on her. They seemed to have much in common. Whenever Jess’s mother, a small, pale woman, visited the Aliens in Rochester or came to the lake cottage for a few weeks in the summer, Mary Jane wanted to spend every moment she could with her grandmother. Grandmother Allen taught her to sew well, and to knit and crochet, and she told Mary Jane stories about her own younger years. Two of her ten children had died in infancy during an influenza epidemic. Grandfather Allen had then died when Jess Allen was still a boy. There had not been much money, and Grandmother Allen had had to struggle to raise her surviving children. She was proud of what she had accomplished, of how well Jess and his seven brothers and sisters had turned out. A woman should take pride in being a mother, she said.

Even though the man might be the provider, raising the family was ultimately the woman’s responsibility. In a time of trouble, a woman should sacrifice for her children, holding them firmly to her and nurturing them into adulthood. If a woman fulfilled her duty to her family, she would also be fulfilling her duty to God and her country, for without the family, the church and the nation could not exist, Mary Jane’s grandmother said.

Mary Jane had been keeping a hope chest for the marriage she dreamed of even before she met John. She started it as soon as she began working part-time in the picture-frame and toy departments at Sibley’s. She bought tablecloths and napkins and pretty ashtrays and other knickknacks. Her mother never objected to the purchases, because Mary Jane had innate good taste. Most of her friends also kept hope chests. After she met John the question of the man was settled. Except for her high school graduation in June 1944, when she went to the prom with a boy who had been a childhood friend, she dated no one during the year and nearly four months until she saw John again. It was romantic to be in love with a serviceman who was fighting, or was preparing to fight, this war for the salvation of the world. Hardly a week passed without the photo of a “war bride” in the society sections of the Rochester newspapers. Mary Jane’s graduation ceremony at West High School was in keeping with this spirit. One of the boys read his essay, “What I Am Fighting For,” and a girl read hers, “Hands Across the Sea.” Another young woman sang a solo entitled “British Children’s Prayer.”

At the classification center in Nashville, Vann had been lucky enough to be selected for pilot training, despite slightly higher scores on the aptitude tests for bombardier and navigator. He passed the winter, spring, and summer of 1944 shifting through the South from one stage of flight training to another—to Primary School at Bainbridge, Georgia, where he survived his initial flying test, a solo after eight to ten hours of instruction; to a faster trainer aircraft, his first formation flying, and instrument training in the simulated cockpits of the Link Trainers at the Basic School at Maxwell Field, Alabama; finally to the thrill of Advanced Flying School at Dorr Field, Florida.

His exuberance and the love of freedom in flight that had drawn him to aviation in the first place then denied him his dream of becoming a pilot. He flew a trainer through some forbidden stunt maneuvers one day in early August. He was punished by dismissal from the school. The language of bureaucracy hid the precise nature of his sin. His record said only: “Eliminated from further Pilot training due to Flying Deficiency.”

He was crestfallen by the penalty for his foolishness and fibbed to his worshipful youngest brother, Gene, saying that the flight surgeons had found a spot on a lung from a childhood case of tuberculosis. (He told Mary Jane the truth years later.) His instructors noted his ability and exemplary behavior most of the time (he had been nominated for the Good Conduct Medal at Maxwell Field) and recommended him for Navigation School at San Marcos Army Air Field in Texas. He was transferred there in October, graduated in late January 1945, and was awarded his navigator’s wings and the gold bars of a second lieutenant in mid-February.

He sent Mary Jane a photograph of himself in his new officer’s uniform, with a short, tight-fitting tunic called the “Ike jacket” because General Eisenhower liked to wear it. The quickie studio where he had the photograph taken had a canvas backdrop painted in sea and clouds. He crushed in his cap at the sides for a rakish aviator effect, put a hand on his hip, and stared off at destiny to the left of the camera. “So help me Hon,” he wrote on the back, “The guy that took this (at a 2 bit carnival)—

made

me stand like this—looking off into the

wild

blue yonder—and Lord alone knows for what.”

John telephoned long-distance in April. He had been granted a short leave in the course of being transferred to Lincoln, Nebraska, and he was coming to see her for the first time since the Christmas Eve dinner. He hitched plane rides from one airfield to another and arrived in Rochester on April 12, 1945. Mary Jane remembered the date because it was the day Franklin Roosevelt died and Harry Truman became president. They went downtown to a jewelry store and he bought her an engagement ring. He didn’t propose marriage, and she did not mention it prior to getting the ring. It was just assumed between them that they would be married.

Mary Allen forced them to agree to wait two years. The Aliens liked their glimpse of the young man, but they wanted to see more before he took their daughter. Mary Allen’s concern with family also made her wish to learn whether his family were her kind of people. She was anxious as well to have her daughter obtain a better education than she had, to have at least two years of college before marrying. After her high school graduation in 1944 Mary Jane had attended Miss McCarthy’s Business School to learn typing and shorthand and had since been working as a secretary. Her mother had set aside money for her to enter the University of Rochester in the fall of 1945.

For the first time in her life, Mary Jane became rebellious. John called that summer from New Mexico, where he had been sent for three months of specialized radar navigation training on the B-29 Superfortress, the four-engine monarch of the World War II bombers, and invited her to come down on a train for a visit. She accepted without obtaining her parents’ permission. They were away on a trip and difficult to reach. She persuaded her older sister, Doris, to act as her chaperon. John arranged for the two girls to stay at a guest house on the air base and found a date for Doris. Both girls had a grand time swimming at the pool and going to parties. In August she pressured her mother into announcing the engagement. The

Rochester Times-Union

carried the notice in its evening edition of Saturday, August 18, 1945, with a studio portrait of Mary Jane.

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA

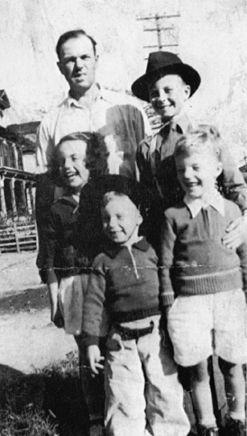

Frank Vann, John Paul’s stepfather, did the cooking; he tried to make the monotonous fried potatoes and biscuits as tasty as possible. Young Johnny in Frank Vann’s hat, Frank Junior, Dorothy Lee, little Gene in his big brother’s Boy Scout hat as cowboy gear.

Courtesy Dorothy Lee Cadorette

.

Gene was the victim of the vitamin-deficient diet. Rickets bowed his legs grotesquely. The surgeons at a charity hospital broke his legs to set them straight and he wore a body cast for eight months.

Courtesy Dorothy Lee Cadorette

.