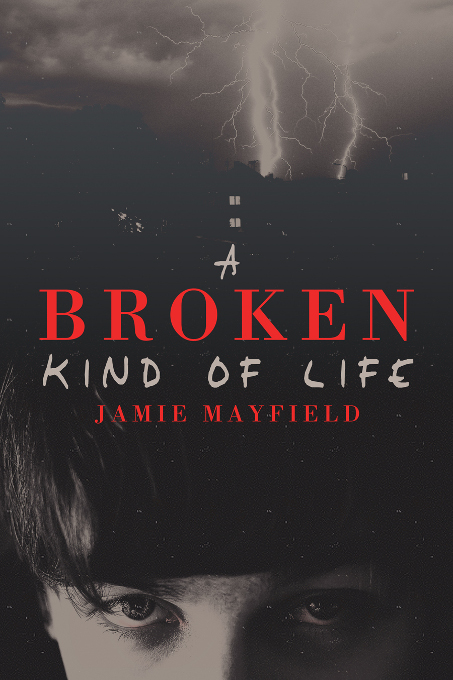

A Broken Kind of Life

Read A Broken Kind of Life Online

Authors: Jamie Mayfield

Published by

Harmony Ink Press

5032 Capital Circle SW

Ste 2, PMB# 279

Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886

USA

http://harmonyinkpress.com

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

A Broken Kind of Life

Copyright © 2013 by Jamie Mayfield

Cover Art by AngstyG, www.angstyg.com

Cover content is being used for illustrative purposes only

and any person depicted on the cover is a model.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact Harmony Ink Press, 5032 Capital Circle SW, Ste 2, PMB# 279, Tallahassee, FL 32305-7886, USA.

ISBN: 978-1-62798-099-9

Library ISBN: 978-1-62798-101-9

Digital ISBN: 978-1-62798-100-2

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

September 2013

Adapted from Aaron by J. P. Barnaby

Library Edition

December 2013

For Kris, one of the best surprises of my writing career, who helps keep the monsters away with his laughter and his light.

U

NTIL

you have endured the violation of abuse, whether by a single, violent act of cruelty or a chronic condition of suffering, you cannot know the meaning of self-loss. It isn’t only the obliteration of all of your belief systems; it is the annihilation of your human worth and the unrecoverable thieving of your self. Painful beyond description in myriad ways, debilitating, and tragic, abuse leaves everlasting, invisible scars. To say that you will recover from abuse, any kind of abuse, including bullying, is a myth. You can only survive and compensate for it when and if you are able.

Hi, I’m Cody Kennedy. It’s no secret that I love stories about hope. As the author of several stories about reclaiming yourself after abuse, I have always tried my best to find new ways to look at what makes each survivor unique and, at the same time, universal. Someone who we can relate to.

Wonderful, courageous, heartrending, and finely tuned to realism,

A Broken Kind of Life

tells the poignant tale of a young man’s devastation and self-resurrection from mere remnants of himself. Aaron is a gay teen who suffers a single, violent assault. Severely physically scarred, his emotions in ruins, and his mind on the brink, Aaron is left adrift in a sea of unbearable humiliation, guilt, isolation, and worst of all, mind-numbing fear. Two years later, Aaron begins the lonely, agonizingly steep crawl up from the depths of hell. When a glimmer appears on the horizon in the form of a young man named Spencer, Aaron’s will to live is rekindled. Complex and broken in vastly different ways, Aaron and Spencer share a purpose: to live life to the fullest no matter their damage and to be loved for who they have become.

Jamie Mayfield puts himself boldly and unconditionally forward as a survivor of abuse and in this story bares but a fraction of what he endured. A master storyteller with a rare talent for grounding stories of survival in everyday reality, Jamie breathes new life into the fragile notion of hope by creating an extraordinary survivor in Aaron. He shows us that abuse doesn’t define us and we should never judge ourselves by what others have done to us. Please join me in lauding Jamie and Aaron. May their legacies endure and inspire past, present, and future survivors for generations to come.

Cody Kennedy

Los Angeles, California

June, 2013

T

HE

boy’s heart slammed against his ribs as his sheets bound him, wrapping pieces of cotton around his trembling arms and legs. Hot breath exploded from his lungs in sharp bursts as he fought against their hold, and he tried but failed to keep the blinding fear at bay. Sweat rolled down his back in the dark, stifling space as his arms pulled free of their nighttime bindings. As he searched the dark corners of his room, several minutes passed before his fear burned off into white-hot rage. Two years had passed since the attack, but night after night, his dreams continued to torture him. It was a wonder he ever slept. Even with the regimen of pills his so-called doctors forced on him, he felt like a walking corpse.

The description fit so well because everything inside him was dead.

He forced down the wave of nausea that plagued him every morning when the drugs wore off and pushed back the blankets. Peering between the heavy blue curtains, he focused on the Midwestern sky outside. Each of his days was full of repetition and habits, some far stranger than others. For example, the weird game of Russian roulette he played with himself each morning said that if the sky was blue and the sun was shining, he could find it within himself to brave just one more day. If, however, he saw a dark and ominous sky, he would roll to his side, face the wall, and pull the covers up over his head. Invariably, his mother would come in to check on him, wanting nothing more than to kiss his forehead or smooth his sleep-disheveled hair, but she never did. Instead, she tried not to mourn the loss of her son but to embrace the broken, disfigured boy left in his place.

The sun’s harsh rays caused him to squint as he gazed through the gap in the curtains, so he forced himself to get up. The long-sleeved T-shirt clung to his body, soaked in the sweat of a late summer morning. The boy bundled clean clothes tight against his chest, thin socks sliding across the slick wooden floor as he shuffled to the bathroom to start his daily routine. Everything in his life revolved around routine. Every mood, every activity, seemingly every thought was closely monitored and controlled through the drugs. Just once, he’d like to get through a day without being nearly incapacitated by fear and pain and be a fully functioning human being again.

At eighteen, his life was over.

The dark hardwood floor, heavily paneled curtains, cherry wood furniture, and navy-blue bedding gave his bedroom a special kind of gloom, so things brightened just a bit in the adjoining bathroom. Decorated in light blues and peach tones, the room had an oceanic theme of shorelines and seashells. The décor should have calmed him, but it didn’t. He probably hated that room more than any other in the house—his nakedness, his reflection, his shame were all on display there, harshly spotlighted by the energy-efficient bulbs in the fixture above the sink. The boy turned on the water in the shower, allowing it to heat to its highest tolerable level, and stepped back. The long-sleeved T-shirt and sweats, which seemed to grow larger with each passing week, fell to the floor along with underwear and socks. Staring at the faded pattern on the shower curtain rather than looking at his own body, he pulled the plastic back and stepped into the tub.

As the water cascaded over his hair and face, he could see each and every one of his scars, even with his eyes closed. They were burned into his retinas like a horrifying roadmap of his mistakes, and it seemed that even a momentary reprieve from them remained beyond his reach. He glanced up and saw his shampoo, bodywash, and other necessities carefully organized in the rack that hung from the shower head. Everything in its place—everything except him—he had no place anymore. He didn’t live; he didn’t fit; he simply existed. The washrag scratched his skin as he washed with practiced, detached efficiency, taking great pains to stop scrubbing when his skin was only pink and not red. Even though it had been over a year since his mother had found him on his knees in the shower, scrubbing his skin raw, he didn’t want to scare her like that again. That morning, just a few months after he’d been released from the hospital, he’d had one of his most vivid and realistic nightmares. When his mother finally talked him out of the shower, she sat with him on the bathroom floor, keeping a foot of space between them while he rubbed aloe into his scarred limbs. The way she strained to keep her hands at her sides made something inside him hurt. She wanted so badly to help him, but she couldn’t.

No one could.

Instead, she filled him with tranquilizers from the stash given to her by his latest shrink and told him stories from his childhood as he stared blankly at the ceiling and tried to find meaning in the tiny patterns in the plaster. The safety and innocence he’d felt as a child had been ripped from him, almost as if they never existed. He had not mentioned that to his mother but remained quiet as she told him how he used to love playing in the bathtub. She tried so hard to reconnect him with that boy. Several shrinks tried the same tactic with him, attempting to reconnect him to his early teenage years. His mother, however, went much further back, trying anything to help her son. It never worked, and he wished it would, even if just for her sake. Unfortunately for them both, the fantasies of deep-sea diver or mad scientist he used to live out on the side of the tub with paper cups and bubbles were over. That boy was dead.

After slamming off the water in the shower, he reached out, ripped the towel from the rack, and pulled it behind the curtain. Steam hung heavy and thick in the small windowless room, and the scent of bodywash, though almost gone, hung with it. The boy swiped a soft towel over his arms, legs, and torso in distracted, automatic movements, but his skin was still damp when he pushed the curtain to the side and grabbed desperately for his clothes. He refused to unlock the bathroom door or even wait until the fan dissipated part of the steam. His shirt stuck to his skin as he dressed, but only when everything was covered, his scarred flesh hidden, could he take a full breath. The black comb shook in his hands as he smoothed down his short hair with a practiced touch, not bothering with gel or spray as other boys his age might be inclined to do. It simply didn’t matter. People saw only one thing when they looked at him: the ugly, jagged scar that ripped his face from right ear to the middle of his throat. So, really, the way he styled his hair, or didn’t, was inconsequential—no one was looking anyway. His parents had considered plastic surgery, but he couldn’t stand the thought of being ripped into again, torn, disfigured, touched by another set of hands, even a doctor’s.

The boy pushed that thought from his mind and started to brush his teeth as he stared at the painting hung over the sink. Calming, almost relaxing, it proved to be the best part of his morning routine. A peace and serenity lay within the complex geometric shapes that filled its black lacquer frame. At first, when he’d come home from the hospital, bandaged and broken, he’d ripped the bathroom mirror from the wall. His mother found him screaming, his hands nearly shredded, as if destroying the mirror would remove the image of his ruined face from his mind. It hadn’t occurred to him to put anything in place of the mirror. However, his mother, the one person who knew him best, felt in some way that the painting would be better than the bare, discolored wall. She had his father hang the painting while she shopped for accessories to match it. It took him nearly six months to realize that she searched for the perfect towels and bought beautiful little shell-shaped soaps because she was at a loss for how to help her broken son. He also realized she had been right; the bare wall would have been a constant reminder of why the mirror was gone. It would have been almost as bad as the mirror itself.