A Cage of Roots (2 page)

Authors: Matt Griffin

A

s another freezing bluster of hail threw itself against him, Fergus hoisted a pile of blocks onto the first bay of scaffold. He didn’t need a ladder. Huge, mountainous Fergus, with pond-green eyes and a bulbous nose set in a bracken of red hair and orange beard. His hands alone were the size of a normal man’s chest, and he delighted anyone who asked with feats of strength. But this was work-time, and great Fergus was hard at it, over-enthusiastically, as was his way.

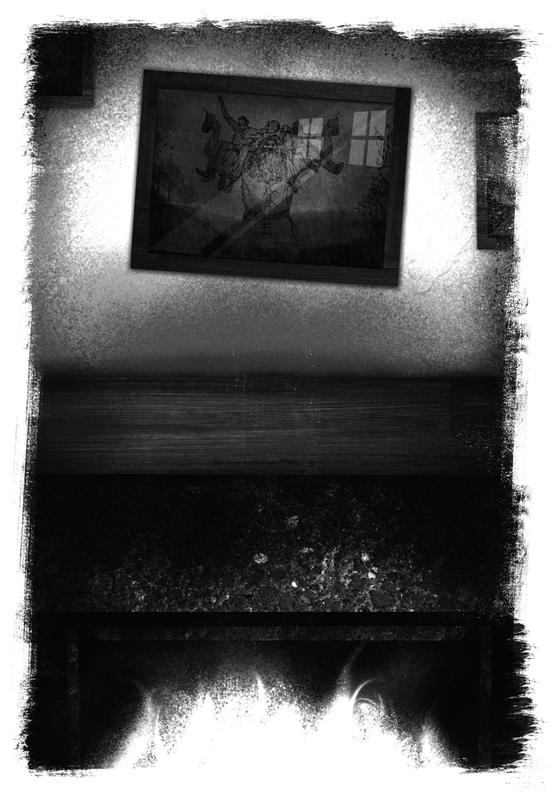

There was a famous photo over the turf fire in Greely’s of Fergus holding a bunch of patrons aloft, three on each arm, while balancing a pint of stout on his head. In this photo, which was the pride of the pub (although no one seemed to remember when it was taken), Fergus’s two brothers can be seen behind him: Taig, fairer than him, and smaller too, although himself well over two-and-a-half metres and a hundred and fifty-odd kilos, laughing his blond head off, and Lann, the eldest, scowling at yet more foolishness from his brother. The picture summed them up pretty well.

Fergus was a behemoth, who loved all the attention he could muster. He was always the loudest voice in Greely’s, the core of the craic. His voice was like a storm in summer, a low boom crackling with drama, so the hairs on your neck would stand up when he spoke, and yet it was full of warmth.

Taig was the musician: expert at the bodhrán, guitar, uilleann pipes and whistle, he could get any foot in the world tapping, and silence it in the next minute with an old air of breathtaking beauty. He was like Fergus in that he loved laughter, and whenever the big man was making a scene, you could be sure Taig would be in stitches beside him.

Lann was different. It wasn’t that he was grim, just that he always seemed like he had serious matters on his mind and no room left for joking. He was renowned as a fair man, a good employer of anyone with decent skill in building, and if you had him build you a house you’d never have to move for the rest of your life. But he was not entirely merry, that was for sure.

Lann’s brow was a ploughed field lined with furrows. His thick, black eyebrows sheltered iron-coloured eyes,

which sat deep in his face, ever watchful. They could bore through a man at fifty metres; the lads on the site often joked that he could shoot lasers out of them! But alas, that wasn’t true. His dark mane was long and tied at the back, his nose and mouth set into his square face like they were carved out of stone. Like Taig, he kept the whiskers off his chin, but his angular jaw was curtained by dense sideburns. He stood just over two metres, with wide shoulders to carry whatever burden it was that kept his mood so serious. He was fearsome to see, for sure. But anyone who knew him knew he was fair, honest and good, and they didn’t fear him unless they were late for work more than once. Like the other two, you wouldn’t be able to guess his age. They all looked young and old at the same time, and in fact it was a common game to guess their age in Greely’s, but the big fellas never told.

The wind was whipping sleet from the west onto the men who worked on the build. It was a big renovation job: Sheedys’, an old farmhouse that sat nestled in thick oak and birch at the foot of some small hillocks near Knockwhite Hill, about five kilometres out of town in the area of Dundearg. A couple from Limerick had bought the old place from Pat Sheedy and they had big changes in store. A new extension built here, outhouses transformed there. If you were lucky on a day like this you were a carpenter or electrician, working inside on the first fix. For the

bricklayers outside, it was less pleasant, especially for Tom Skellig, whose toes were nearly crushed by another row of blocks dumped at his feet by over-zealous Fergus.

‘Mind Tom’s feet, for God’s sake, Fergus!’ Lann shouted, as the red giant hoisted yet another row of seven blocks onto the scaffold and slammed them down to be met, as Lann had expected, with a holler from poor Tom.

‘Ah, Jaysus, Fergus!’ Tom squealed, clutching his foot and trying to get the boot off. ‘Even with steel-toed boots I’m not safe!’

He got the mangled boot off and began to blow on his foot.

‘Ah, did Poor Possum hurt his little toe-toes?’ Fergus chided, while laughter trickled down from Taig, skipping between the higher levels of scaffold.

Lann brought his fist down on the plans in frustration. He had been using a pile of blocks as a table. Several of them cracked.

‘Stop!’ yelled Lann, with a keen edge of anger in his voice. It was a rare baring of teeth from the oldest brother, and it was enough to quieten the whole site, including his brothers.

‘Sorry, Lann,’ said Fergus, and he gently lifted just a couple of blocks onto the platform, well away from Tom.

Lann frowned down upon the now-torn plans. He knew it was unusual for him to be so quick to temper.

Sure, the architect was proving to be a bit of a pain in his neck – a posh fella from Dublin, and prone to change his plans – but something else was agitating him, and what it was he couldn’t say or put his finger on. He just had an ill feeling about the day, and this was a feeling he had learned not to ignore over the years. For now though, he just couldn’t nail it down.

He took out his phone and looked at the photo of Ayla, for the picture always calmed him. He stared into the green eyes, glimmering between the masses of amber curls, and checked himself for losing his temper. He knew Ayla would disapprove if she were there. ‘Sorry pet,’ he muttered, and put the phone back in his pocket. Before he could return to the plans, he heard a polite cough behind him.

Mr Fitzgerald, the architect, stood beside him wearing all the gear: hard hat with built-in ear-guards and visor, hi-viz jacket, vest and pants, and brand new boots without a single scuff. Behind him were the couple that had bought the house; all three held umbrellas pointlessly against the sleet. The wind swept up and under and from the side, and paid no heed to brollies.

Lann barely noticed the rain bouncing off his face. This was a scheduled visit; he had just uncharacteristically forgotten about it. It was the last thing he needed today.

‘What can I do for you, Mr Fitzgerald?’ he asked.

‘Hello Lann. How’s it going? Horrible day so it is,’ the

architect replied in his tangy South-Dublin drawl.

‘Soft enough alright,’ replied Lann, as the icy wind broke another wave of hail against his cheek.

‘Well, you’ll remember I let you know we would be coming by to discuss a few adjustments. We have a small change or two anyway.’

The changes were anything but small, and the architect’s voice seemed to shake with pride at his own visionary abilities.

‘It’s all been approved at the planners. Here’s the USB with the new plans, and of course a printed copy – we know you don’t like computers!’ he finished with a smile. The couple attempted to grin expectantly behind him, but they just ended up wincing against the pelting wet.

Briefly, Lann considered shouting at all of them, but withheld his frustration and simply announced to the site: ‘Tom! Stop. Fergus, take the blocks down. Taig! Put that scaffold back up!’ He turned to the three visitors. ‘No worries.’

Mr Fitzgerald smiled, satisfied his power over such a giant had not waned. ‘Good man, Lann. Now, we also wanted to look into the structure in the northeast corner, the little rocky hillock. We talked about this bef—’

But before he could finish, Lann held up a great slab of hand.

‘That’ll be all for now, Mr Fitzgerald. We’ve enough to be getting on with.’

‘But, eh, Lann, we’ve been wanting to talk about this before and …’

Lann had returned to his desk of grey blocks, turning his back to the three drowned visitors.

‘We’ll talk about it again. We have a lot to be doing. Mr and Mrs Moran, feel free to head on in to the main house and take a look around, but take a hat from the office first and no going into the extension. We’ll be taking half of it down now.’

There was a tone in his voice that said ‘This is not up for negotiation’, and the three headed to the prefab office to fetch another couple of hard hats. Lann muttered under his breath, crumpled the torn plans into a ball, and sighed, casting his iron eyes to the stony hillock in the northeast corner.

Finny’s knees ached from kneeling on the hardwood floor. He was only about a tenth of the way through the ‘S’s’ in the old phone book, and already he had been there for at least an hour and a half. Writing out a letter of Fr Shanlon’s 1993 Telecom Éireann phone book was the lanky priest’s favourite penance, and Finny seemed to have to do it every second day. He wouldn’t mind, but it wasn’t even for doing anything bad. In his school, the slightest step out

of line meant big punishment. But big punishment was fine by him, and the more they gave out to him, the harder he pushed back.

It wasn’t so much that he loved to cause trouble – it was more that he hated being told what to do, especially by grown-ups. He had no faith in their authority, let alone any respect for it, and it made him angry whenever he thought about how they tried to control him, to push and pull and tug at him, constantly. He just wanted to be left alone, to hang out with his friends who never tried to direct or persuade him. Ayla, especially, just let him be.

He did miss the hurling; that part stung. But it was the same out there on the pitch – they just wouldn’t let him express himself.

Run here, mark him, you should be here,

they would shout, and he would shut them up with a point from halfway. They hit him where it hurt now anyway – no hurling as long as he made trouble.

Their loss,

he thought defiantly.

This particular purgatory was brought on by one of Finny’s favourite pastimes – a spot-on impression of The Streak himself, the Principal of St Augustin’s: Fr Donnacha Shanlon. Fr Shanlon was apparently an immortal – by all accounts, he had been in the school since before prehistory. You could find the yellowest, grungiest, antique relic of a photo in the most remote corner of the school and you could be sure the first person you’d notice in it

would be The Streak, arching over everyone else like an imposing old oak.

He was called ‘The Streak’ on account of two things: first, his ominous height. Fr Shanlon, at nearly two-and-a-half metres, was definitely the tallest priest anyone in Kilnabracka, or, indeed, the whole of Limerick, had ever seen. At the crown of this commanding tree-trunk was his head – bald and large, it flowed towards the point of his hawk’s-beak nose. Either side of this prominent bill, and squatting beneath hedgehog eyebrows, sat two dark eyes, sunk deep. His dark eyes occasionally appeared a vivid green, so that on the rare occasion you witnessed the light hitting them they looked like two gemstones set in some ancient gargoyle.