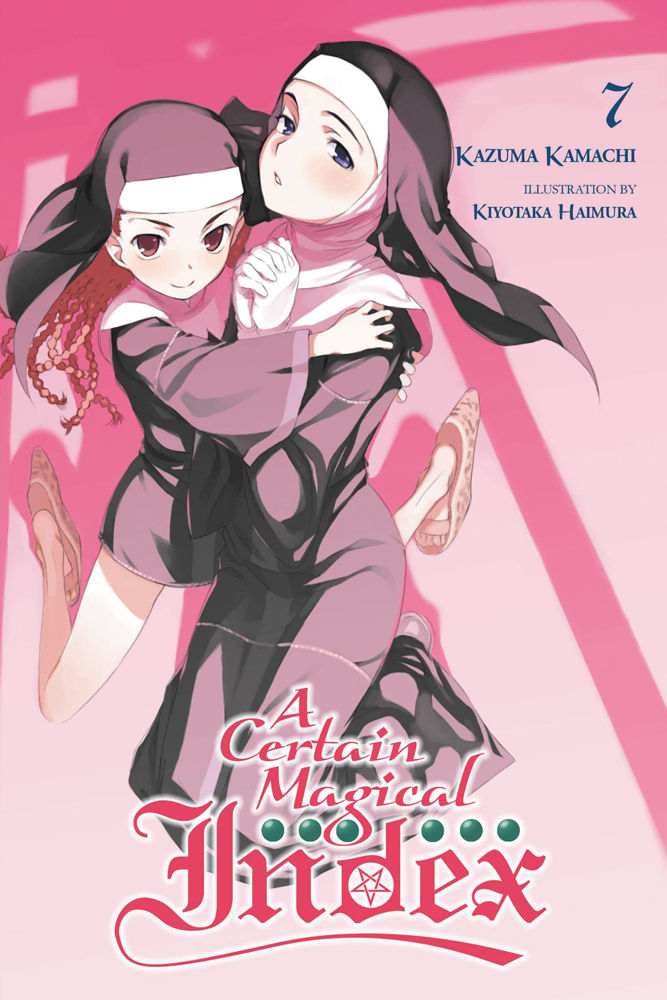

A Certain Magical Index, Vol. 7

The Opening Move

The_Page_is_Opened.

St. George’s Cathedral.

Despite the moniker of “cathedral,” it was just one of many churches located in inner London. It was a fairly large building, but compared to internationally popular sightseeing spots like Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s Cathedral, it was exceptionally small. And, of course, it didn’t come close to the Canterbury Cathedral, said to be where English Puritanism began.

Besides, there were many buildings in London named after Saint George. Churches were one thing, but there were also department stores, restaurants, boutiques, and schools sharing the name. There were likely dozens of St. Georges just within the city borders. And there may have even been more than ten St. George’s Cathedrals in the first place—after all, the name was so famous it was even tied into the national flag.

Since its construction, St. George’s Cathedral was the headquarters of Necessarius, the Church of Necessary Evils.

It wasn’t a good connotation. Those who were a part of Necessarius were members of the Church, and yet they used tainted magic. Their duty was to aggressively destroy sorcerer’s societies in England and annihilate the sorcerers belonging to them. They were considered boorish and uncouth by English Puritans, so they were moved out of Canterbury, the head church of English Puritanism, and relegated to St. George’s Cathedral in what amounted to a demotion.

However…

Though it was once nothing more than a window-side post, Necessarius was silently but fervently bearing fruit.

And these actions granted them trust and privileges within the grand organization known as the Established Church. They did so well that while the heart of English Puritanism was still officially the Canterbury Cathedral, its mind had been entirely surrendered to St. George’s Cathedral.

That was how this cathedral, just a stone’s throw away from the center of London, had become the core of the largest religion in the country.

One morning, a red-haired priest named Stiyl Magnus was walking through London’s streets, fretting to himself.

The city itself didn’t look any different. Stone-built apartments constructed a little over three hundred years ago stood lining either side of the road as office workers hurried down it, their cell phones in their hands. At the same time traditional double-decker buses drove slowly by, the equally traditional red phone boxes were being steadily removed by construction workers. It was the same scenery as always—an amalgamation of the old and the new.

The weather hadn’t changed, either. The skies over London this morning were clear enough for the sun to shine through, but the weather in this city was so hard to predict that nobody could really know what it would be like even four hours later, and many carried umbrellas with them. And it was hot and humid. London was known as the city of fog, but its volatile summertime weather was another problem entirely. Intermittent rain would bring nearby temperatures up, while the hot foehn wind and heat waves, growing more prevalent in recent years, led to extreme heat. Even snug little sightseeing spots had problems. Of course, Stiyl had chosen to live in this city in spite of its issues, so he didn’t particularly mind.

The problem was the girl walking beside him.

“Archbishop!”

“Mm. I implore you, my good sir, do not call my name in such a

grand manner. Today I have at last chosen a simple, plain outfit, you see,” proclaimed a carefree voice in Japanese.

The voice belonged to a girl who looked about eighteen, clad in a simple beige habit. Incidentally, holy garb was supposed to be either white, red, black, green, or purple, and the embroidery could only be made with gold thread—so she may have been bending the rules a bit.

She was probably the only person who thought her outfit was blending in with the people in the city. Her skin was so fair it shone, and her eyes were a perfectly clear blue. Her hair, which looked like something that would be sold by a vendor of precious gems, utterly failed to fit in with the crowd.

Her hair was abnormally long, too. She wore it straight down—but at her ankles, it turned up and went back to her head. It was held there by a big silver barrette…and then it went all the way down to her waist again. Its length was roughly two and a half times her height.

London’s morning rush hour—and Lambeth’s in particular—was one of the most congested in the world, but nevertheless it seemed like the volume of nearby sounds was being lowered. Even the air around them felt akin to the silence called for in a cathedral.

She was the archbishop of the 0th parish of the English Puritan Church, Necessarius—the Church of Necessary Evils.

Laura Stuart.

The English Puritan Church’s leader was the reigning king. And beside him was Laura…the highest archbishop, whose role it was to command the Church in place of the king, who was normally extremely busy.

The organization of English Puritanism was like an antique stringed instrument.

While the tool had an owner, a caretaker carried out the tool’s maintenance and repairs. It didn’t matter how excellent the violin was—if not used, its strings would slacken before you knew it, its sound box would be damaged, and the sounds it played would grow hoarse. Laura was the temporary performing musician who prevented that.