A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy (16 page)

Read A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy Online

Authors: Eric Lamet

It was getting late and we did not have a place to rest. As we left the large house and walked into the square, we saw the sun about to set behind the mountain. The time was a little after five and soon it would be dark.

“I didn't expect we would have such a problem,”

Mutti

said.

A man directed us to the next address on the list. The house was just up the street from the ex-mayor's home, but our steps lacked the optimistic bounce they had had when walking toward the house with running water.

We approached a small white building and found a clean home and an amiable landlady happy to show us around. The room she had to rent was spotless, perhaps even redecorated and nicer than anything we had seen so far. The furniture was plain but in good condition. We were tired, so Mother did not ask to to see the toilet.

“I like you, Signora Antonietta. How much are you asking for the room?”

“Fifty lire. If that is too much, I may take five lire less.”

Mamma looked overjoyed and, without hesitation, made her decision. “That's just fine. I believe we'll be happy here.” She looked at me. “We'll take it, Enrico.”

Getting Settled

A

ntonietta Matarazzo looked older than her thirty-two years. Perhaps it was the old-fashioned country hairdo — gathered in a tight tress and rolled into a bun — or the dark-colored, plain dress that added years to the women of this village. She wore wooden

zoccoli

, reminiscent of the Dutch shoes.

Zoccoli

served well inside the house and out, summer or winter yet never wore out, for the wooden soles were thick enough to last a lifetime.

“Where is your luggage?” asked Antonietta.

“It is at the

caserma dei carabinieri

,” Mother replied.

Antonietta walked to the front door. “

Che vulite

?” she asked the two boys standing outside, who had followed us since we left the police station. While shaking her outstretched fingers in admonishment, she ordered the youths to get our suitcases. “And hurry up!”

It took the boys two trips. The last suitcase secured in our room, Antonietta gave them a few lire. “It's better I take care of them,” she explained. “These thieves will steal the eyes from your head.”

Before the day was over and, in spite of her lack of sleep, Mamma had found a place for most of our belongings. The suitcases, only partially emptied, I shoved under the high brass bed. The dresser Mother decorated with a crocheted doily from our home in Vienna. A small vase arranged with wild flowers, courtesy of Antonietta, added a smile to the room. Only the large cross, prominently hanging over the bed, did not belong in our bedroom. For Mamma this created a big dilemma.

“I don't know what to do with this? I don't want to sleep under it.”

“I'll sleep over it, if that will make you happier,” I offered.

“Oh, stop it,”

Mutti

said smiling. “I'm serious. I'm afraid to take it down. It might offend Signora Antonietta.”

Exhausted, we let practicality win over conviction and left the crucifix in its place. Earlier than usual and without eating, I fell into a deep sleep.

When I awoke the next morning, Mother, as was her custom, was already up and out of the room. The sun struggled through the narrow slits of the French shutters. The thin rays formed a geometric pattern on the wall, giving the room the look of a still-life painting. It felt good lingering in bed after a good night's rest.

From the corner of my eye, I caught a glimpse of something moving on the wall not far from my head. With a jump I sat up. A dark brown animal, the length of a cigarette pack and with an erect tail that doubled its total size, was crawling on the white wall. Scared by the sinister-looking creature, I let out a shriek.

Mother came running. “What is it?”

I pointed at the threatening form on the wall, making sure my finger remained at a safe distance. “Look!”

From her gaze, it didn't take me long to realize she was not going to be of any help. I couldn't tell who was more afraid, me or

Mutti

. Taking away my only protection, Mother yanked the covers off and jumped back. “Get out of bed.”

Attracted by the commotion, Antonietta peered into the room. “Anything wrong?” she asked.

“What is that thing?” Mamma asked.

“Oh, that? It's nothing. It's just a small scorpion.”

“A small scorpion?” I repeated. “What does a large one look like?”

“Well, they get to be two or three times that size, sometimes larger.”

The sight that terrorized both my mother and me did not bother our landlady at all.

“Do they bite?” Mamma asked.

“They don't exactly bite,” Antonietta replied. “They sting with their tail. People have been known to die of the poison.” All the while our landlady kept her eyes fixed on the scorpion. Then, with one of her wooden shoes in hand, she hobbled up to the head of the bed and delivered a mortal blow to the pest, which curled on itself as it fell to the tiled floor behind the brass headboard.

As though other options were available to me, I announced, “I'm not sleeping here again.”

Antonietta left the room and quickly returned with broom in hand to sweep the dead body from under the bed.

Ospedaletto d'Alpinolo was infested with many insects, spiders, and other more or less repulsive inhabitants. These creatures were part of everyday life and townspeople accepted them. Flies and fleas were harmless though annoying and we soon resigned ourselves to their presence. But mice, lice, scorpions, and cockroaches we just couldn't handle.

“How are we going to live with these horrible beasts, Mamma?” I asked.

“

Non so, ma ci dovremo adattare

.” Mother usually spoke to me in German, for she didn't want me to forget my mother tongue but, when I started the conversation in Italian, she generally continued in the same language.

“I'd like to see you get used to mice,” I said. Mamma was terrified of rodents and, no matter how small, the mere appearance of a mouse turned her into an Olympic high jumper.

In so many ways, Ospedaletto represented a step back in time. Life in this isolated village was not set in 1941, but rather the way it must have been at the end of the previous century in other parts of Italy. Superstition ruled people's lives. Except for the ex-mayor's home, no other home had running water. Just the simple act of washing our faces took us back to the past. And although electricity was in almost every home, electric outlets were a rarity.

After my dramatic encounter with the scorpion, I was faced with a new dilemma: I had to relearn how to wash myself. Antonietta had filled a carafe with fresh, cool mountain water and placed it alongside a ceramic basin sitting on its own stand. I poured some water into the bowl and stood there baffled as to what to do next. Should I wash my hands, then use the dirty water to wash my face, or should I do it the other way around without knowing if my hands were clean enough for that task? For no rational reason, I decided to wash my face first.

I found Mamma in the kitchen. She was elated. Antonietta had invited her to use the clean and well-equipped kitchen. It was good to enjoy Mother's breakfast, after which I ventured out.

The air was crisp from the night's coolness but fast warming in the bright sun. The day would soon become another scorcher. I stood at the door, wondering for a moment which direction to take. Then down the two house steps I jumped, turned left, and walked about one hundred yards to the town's square.

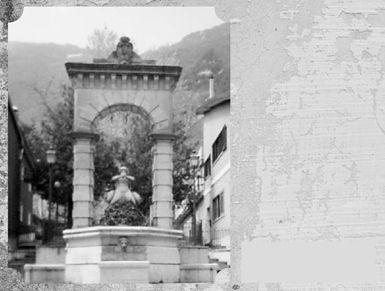

Italian villages and towns, just like cities, all have a central piazza and a separate municipal garden where a monument to fallen soldiers or a statue of Garibaldi or of one of the kings of the house of Savoy stands. In Ospedaletto the piazza and the garden were one and the same and no statue had ever been erected. Except for a few wooden benches, a

boccie

field, a sculpted stone water fountain, and several large trees, the park was bare.

The clear stream of uninterrupted flow from the mountain, spurting from the fountain's single lion head, sent out a tempting invitation. The water was ice cold, sparkling clear, reflecting the purity of the surrounding nature. Holding my fingers under the fast-moving stream I tasted the droplets. Hastily, I cupped my hands to drink the water and the more I drank, the more I craved it. My thirst refused to be satisfied. To bring my mouth near the gush of the precious gift, I clambered up and half-sat on the edge of the narrow stone that was the fountain's cradle. Only the arrival of a young woman, who had come to fill a large vessel, made me jump off to make room for her.

The fountain in the main square, Ospedaletto.

She rested a large copper cauldron on the metal grate. This was heavy, judging from the thud it created. The fast rushing water quickly filled the container. While the vessel was filling, I watched the girl twist a large rag around one hand to form a ring, then position it on her head. She was small and surely not more than three or four years older than I. How was she going to carry that heavy container? To my great surprise she slid the filled vessel onto one hand, tipped it to spill off the surplus water and, with a twist of her body, lifted and positioned the container on the curled rag she had placed on her head. Her legs spaced apart to gain balance, she grasped the vessel's handles and stabilized it. Then, with her back erect and a distinct rhythm, she waddled down the dirt road, letting her bare feet absorb the full brunt of the pebbly path. Soon the girl was lost in the distance.

More women and girls came to the fountain to fill their containers, but on that morning I never saw a man carry more than a small pail. As soon as the fountain was available, I gulped down a few more sips of the refreshing gift of nature before setting off to explore the village.

I hopped down the steep, dusty, gravel street that cut through the heart of the village. The road was narrow, just wide enough for a horse and buggy or a small passenger car. Every one of my hops raised a puff of dust and shot the sharp feeling of each stone through my leather sandals, adding to my admiration of the skill needed for the girl to balance that heavy load barefooted.

Located at midpoint between Avellino and the monastery of Montevergine, Ospedaletto d'Alpinolo was bordered by dense chestnut forests on two mountainsides. The other fringes overlooked a vast valley embracing the provincial town of Avellino below. A sign, posted on the first house at each end of the village read: “Ospedaletto d'Alpinolo, 725 msm 1825 pop” (725 meters, or 2,200 feet above sea level, with a population of 1,825).

The road formed a twisted shortcut from one end of town to the other. Passing by the

carabinieri

station, I was comforted to recognize a familiar sight. Down the incline I passed the boarded stores and the open barber shop, where a row of colorful strands of wooden beads, extending the width of the entrance, hung from ceiling to floor. I peeked inside.

“

Buongiorno

. What are these things for?” I asked, pointing to the hanging beads.

Their constant swaying helped keep flies out, I was told. Similar beads hung from the

caffê

and other shop doorways.

I was struck by the sameness of the two-story whitewashed houses joined into one continuous chain. Unlike San Remo's, Ospedaletto's houses all looked alike. The only difference was in their outside colors, which ranged from dull white to dirty gray.

My hopping brought me to the small piazza in the village center, where the church stood. There, the road turned ninety degrees to the left before ending at the edge of town.

In less than an hour I had covered the village from one corner to the other. The large bell atop the steeple, reverberating in my ears, signaled 10:00.

Just as the raising of the theater curtain signals for the action to begin, so the clang of the bell awoke a flurry of new activities. A bare-footed boy about my age swung open the

caffê

doors, then untied and let drop the multicolored beads. Slipping inside several times, he carried four timeworn tables and several chairs out into the square. Women flung open the shutters of the surrounding homes and using flexible tree branches, they beat the dust out of blankets, pillows, and rugs.

The cobbler, in black pants, white shirt, black open vest, and an apron, brought out his small work stand that held all the nails and tools of his trade.

Curious, I waited to watch the man set up shop. He reappeared again carrying a three legged stool and a pair of unfinished shoes stretched over wooden lasts.

Straddling the stool, the man looked up at me, mumbled a greeting, and commenced his work. Holding one wooden last between his thighs, he placed a handful of small tacks in his mouth and, one by one, fed the tiny nails to his fingers. He stabbed each tack into the leather, while the hammer, in a well coordinated motion, pounced on the nail, hammering it into the awaiting shoe just as the fingers nimbly slipped out of the way.

“My name is Enrico. We've just come to Ospedaletto,” I said.

With his mouth full of nails, he could only grunt and shake his head.