A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy (44 page)

Read A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy Online

Authors: Eric Lamet

Mr. and Mrs. Rozental and Runia Kleinerman in Naples, 1945.

The synagogue in Naples was hidden on the second floor of an old building buried behind some antique structures, possibly why the Germans never made an attempt to destroy it. It was a small place of worship, but large enough for a portion of the Neapolitan Jewish community that at most totaled four hundred.

True to her Jewish heritage and in honor of our family, which may no longer have been alive, my mother had arranged for my Hebrew studies with the rabbi, and that same month of May, fifteen years old and wrapped in a new prayer shawl, I was called to the

bima,

where, with pride, I read the Torah and became Bar Mitzvah.

Throughout 1945, we heard nothing from my father nor from any of our relatives and in 1946, seven years after my papa's last letter, long enough to satisfy Italian law, a court declared my dad legally dead. I was devastated, not yet able or willing to come to grips with that possibility. That Raffaele's father was dead I could accept, for he had died before my very eyes. But my papa dead? That was something else. How could some judge, who did not know my dad, who had not seen him die, just write on a piece of paper “Deceased”?

Shortly after the war's end, we were able to contact the Wovsis' sons in Milan. They had terrible news. Soon after their parents had returned home, they had been arrested by the Gestapo and shipped to a concentration camp. They never returned. I asked myself, was it fate or the sadistic delight of some supernatural creature, cynically toying with the lives of so many innocent human beings? What had passed me by when I was eleven now, five years later, made a profound impression as I tried to absorb all that had happened since our escape from Vienna.

In the late fall of 1946, while I was attending boarding school near Florence to repeat the year of high school I had failed, a miracle happened. Through my mother's niece, Toni Hübner, who had lived in Tel Aviv since before the war and was our only relative not to have moved, we received a postcard with the astonishing and unbelievable news that Papa was alive and searching for us.

Giorgio Kleinerman, on furlough, with his mother at the fountain in Naples in February 1945.

Mother made contact with my father, then wrote to tell me he would be visiting me at school. From the moment I received her note, my behavior radically changed. I became restless and unable to concentrate on my studies. It had been eight interminably long years since I had last seen my papa, and now I looked forward to picking up where we had been forced to leave off. What good fortune! Despite the death and destruction that had engulfed Europe, at least my immediate family had remained alive. True, Pietro had assumed a very important place in my life. I respected him and loved him more than I could have loved anyone. He had acted as my father for four years. Except now, I was about to be reunited with my real father. And if my papa was alive, I was optimistic that the rest of my family might be alive too.

I knew it all along. That judge had been wrong. But now what? Mother had set up house with Pietro and was known as Mrs. Russo. Would all that change? I did not know then that my father had already visited with Mother and learned what for him must have been a painful truth. His wife was in love with another man and no longer willing to reunite with him.

On the day my father was to arrive, I was given permission to leave school to meet him at the railroad station. From the moment I awoke, before the 6:00 wake-up bell, my emotions were out of control. I must have looked at my watch a hundred times. In class I was unable to sit still or pay attention and was reprimanded a few times until I told the teacher the reason for my agitation.

Thirty minutes before the train's scheduled arrival, wearing the compulsory boarding school uniform, I entered the station to wait for the man whose face I remembered so well. The Prato station was a small terminal. The platform, short and set between two tracks, served both for arriving and departing passengers. Many trains sped by and with each sound of a locomotive's whistle, my heart picked up its beat. But very few trains stopped. I so wished

Mutti

had been with me. This could have been such a fantastic family reunion. What about

Pupo

now that my papa was alive? Mother had not said anything about her plans in her letter to me.

I waited and paced on the narrow concrete strip for the longest time. Several trains stopped, passengers stepped off, others departed. So many thoughts rushed through my head. At sixteen, I had been without my papa for half of my life! An eternity! Would he even recognize me? I was a little kid the last time he saw me.

Another train slowed and came to a full stop. People got off. With accelerated breathing I scrutinized every man's face. I witnessed happy reunions of men embracing women and children hugging parents. I envisioned Papa rushing to put his arms around me, trying to pick me up, as he had done eight years before. “I'm too heavy, Papa,” I would say. But there was no sight of my father. One by one, the people disappeared down the stairway. Watching the last person leave, my heart lost its beat and hope had vanished. All alone, I did not know what to do.

One person was still on the platform. I had not seen him get off the train. An older man, stooped over, walking with a cane. I paid no attention until I heard a faint call: “Erich?” A cold chill ran through my whole being. That voice. I knew that voice. With calculated steps, we moved toward each other. I saw the man, a broken-down human being, dragging a poorly healed leg and showing the remaining effects of starvation. His hair was combed back tightly as it had been in years past, but it was not the dark, lustrous hair I remembered so well. His face was gaunt and drawn, its red blood vessels visible through the concave cheeks. The suit, too large for his diminished frame, did not resemble any of the dapper clothes he had worn years before. The dream of my father, as I had seen him last at the train station in Milan, the dream I had kept alive all those years in France, San Remo, Ospedaletto, and Naples, crumbled. The elegant picture of my father, the image I had jealously preserved for so many difficult years, was destroyed in a few, short seconds on that railroad platform in Prato.

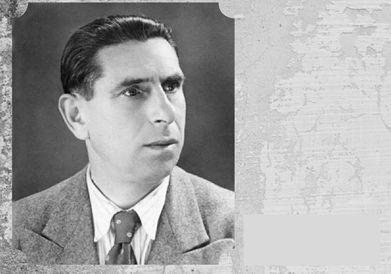

Eric's father after his return in Siberia in 1946.

“Is this my little

Erichl

?” the stranger asked. His voice lacked the assurance I remembered. “Let me look at you.” The words sounded apologetic. He embraced me with caution. I was too shocked to hug him back, as I had so hopefully fantasized I would. He clung to me and I, very slowly, tried to cling to him.

When we let go, stepped back and looked at each other, the questions poured forth.

“What did you do during the war? Did you have enough to eat?” he asked in an old voice. Much older than his forty-nine years.

He described how he had escaped Lwow after the German invasion of Poland only to be caught by the Russians and sent to a concentration camp in Siberia. There he came close to dying of starvation and broke his leg in an accident. He knew nothing of his parents or the other members of the family.

We sat on a wooden bench and talked for about two hours. I know we cried a lot, but possibly, because these details were so painful to hear and my disillusionment so profound, I was incapable or perhaps unwilling to remember most of that event in my conscious memory.

Papa inquired about Signor Russo. Did I like living with him? Was he nice to me? I knew then that my parents had already spoken and Dad knew of my mother's final decision. At that instant, in spite of the pain that wrenched my soul, listening to the sadness in his voice and looking at the shadow of the man I had once known, I realized that nothing that had happened to me could compare with the pain and suffering that had befallen him.

My only solace was that my papa was not dead. He was seated next to me, although he was not the man I remembered. In his eyes was that same melancholic look I had seen at the Milan railroad station on the day

Mutti

and I departed for France.

My own feelings of disappointment gave way to the pity I now felt for my own father. I had never asked myself to choose which man I wanted for my papa. I loved Pietro more than a child could love a parent, but I loved my father, too. Sitting on that bare, wooden bench, older and more knowledgeable, I came to the painful realization that both men could not be part of my daily life.

Papa was going back to a refugee camp in Austria. His train arrived and, once again in a railroad station, we found ourselves bidding each other goodbye. We held hands for a long time and kissed. But by then, I didn't want to let go.

I had lost my relatives and my youth. The train, which I had hoped would never come, was on the tracks. Papa slowly dragged his poorly healed leg to the open door of the third-class cabin. He grasped the handle and with great effort pulled himself up the four high steps. From the platform he stopped and turned to look at me. The shrill locomotive whistle intensified my pain. Through swollen eyes I saw Papa's arm waving and, as the train diminished from view, I realized the painful truth: I was losing my father once again.

When I returned home to Naples in the summer of 1947, I tried to speak to Mother about my father. She told me it was strictly between the two of them and there was nothing to discuss.

Being home, I began to appreciate the relationship that existed between Mamma and Pietro. Their friends talked about it.

Pupo

idolized my mother and carried her on a pedestal. In all the years we lived together I never heard him utter a harsh word to her. Never would Pietro leave or return home without kissing Mother and me, a warm practice we enjoyed all the years we were together, one I continue with my own family. Perhaps my mother was the stronger of the two, but Pietro gave in to her not out of weakness but out of love. I rejoiced in the atmosphere of their mutual adoration. Mamma had finally found her well-deserved happiness.

At seventeen I reexamined what life had been when we lived with my father. Arguments had been more numerous and the criticisms my mother expressed about my father all suggested that their marriage was not as solid as I had wanted to believe. Mother's falling in love with Pietro was a natural outcome.

By 1946, life in Italy had normalized. The war had become an ugly memory. Goods were plentiful and the stores were full of merchandise, theaters competed with dazzling vaudeville shows, people were working and the horrors of the war were slowly being put aside. That year we made our first visit to Sicily. We traveled by boat to Palermo and from there boarded a

rapido

train to Mazara del Vallo. The Russo family was at the station to welcome us. It was a large family. Pietro had six siblings living in Sicily and they were all there. The reception was overwhelming. The warmth of the island was not only in the air but in part of every Sicilian's temperament.

Summer was a period of intense activity on the island. It was harvest time — grapes and wheat and the Russo family had plenty of both. Every day I enjoyed riding the horse-drawn buggy with Pietro to one of several of their farms. Lunch, the big meal of the day, we ate together with the more than twenty-five workers. The huge table, with retaining ledges to prevent food from falling off, served as a gigantic communal platter for the mountain of homemade pasta prepared for all to enjoy. What an experience! No plates, just loads of pasta.

Our one-month stay in Sicily was a true delight. We met many of Pietro's friends and every day was a different occasion for celebration. We liked the family and they liked us.

But all was not smooth. During our stay, Pietro's family learned of our Jewishness. To people who lived by the teachings of the Catholic church in a small Sicilian town, the idea of a Jewish woman becoming part of their family was inconceivable. From childhood they had been taught to believe that Jews were the killers of Christ. How could Pietro think of marrying a woman who had yet not been redeemed in the eyes of the church?

I had not been aware of the problem that was brewing between Pietro and his family but learned the facts much later. One by one, three of Pietro's siblings traveled to Naples to convince him to abandon his relationship with my mother. This fervently Catholic family was intent on obstructing my mother and me from becoming part of them. But all their attempts at convincing Pietro failed and only helped to create a schism between Pietro and his siblings, one of the reasons we eventually would leave Europe.